The Landslide Blog is written by Dave Petley, who is widely recognized as a world leader in the study and management of landslides.

The Western Ghats area of Kerala in SW India has a significant landslide problem in the SW summer monsoon period. This is a tropical, hilly region (elevations extend to over 2,500 metres) that is famed for tea plantations, a land use that is, of course, far from natural. An interesting paper in the journal Anthropocene Science (George et al. 2025) considers approaches that can be used to assess landslide risk in a part of this area. The authors note that the research was inspired by the 6 August 2020 Pettimudi landslide, of which they provide an interesting description.

The Pettimudi landslide was triggered at 22:45 local time by an extreme rainfall event. George et al. (2025) have obtained data from a forest department rain gauge located close to the landslide site, which indicates that 616.2 mm of rainfall fell that day.

The Google Earth image below shows the site of the landslide, with the marker located at the crown of the failure [ at 10.171, 77.0113]:-

As the image shows, this is steep terrain, with the upper part of the slope having forest cover. This is an image of the site after the landslide:-

And below is a slider to allow the two images to be compared:-

The images clearly show that this was a channelised debris flow with a length of about 1.4 km, which started as a shallow failure high on the slope. It is interesting to look in more detail at the source zone of the landslide:-

It appears that the failure started as a small, shallow failure in the interface between the regolith and the bedrock, which then entrained more regolith from the slopes below. It is likely that this would have been a rapid, violent event.

The landslide tore through the tea plantation located on the lower slope. This is a Google Earth image of this area before the failure:-

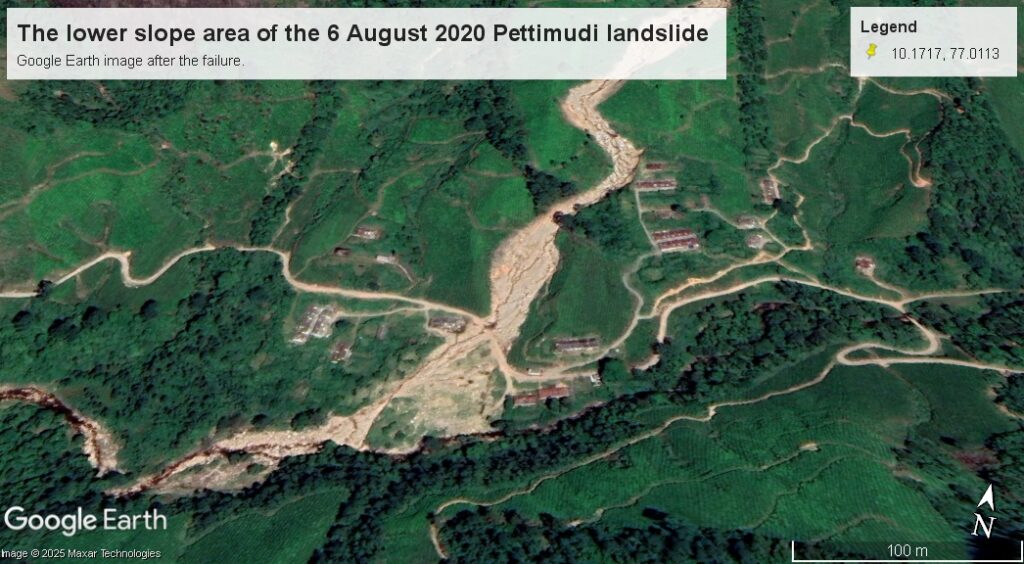

Note the large buildings in this area. George et al. (2025) describe these as labourers’ quarters for the team plantation, known locally called “Layams”. The Google Earth image below shows the aftermath of the landslide in this area:-

A slider to compare these two images is chilling:-

As the images show, the landslide destroyed two of the Layams. It left 76 people, including a number of children, confirmed killed, whilst the remains of another four individuals were not recovered. Only 12 people survived in these buildings.

Anticipating and preventing a landslide of this type is exceptionally challenging. Technically, check dams or barriers in the channel could have intercepted the flow, but to manage the risk in this way would mean building such structures in many channels, which is unlikely to be feasible. Realistically, therefore, mitigation should focus on vulnerability. Close examination of the pre-failure images shows that the layams that were destroyed were located in channels that are clearly prone to large-scale flows, and indeed may have been built on the deposits of previous events. The layams located away from the channels were spared (although in at least one case, it was a near-miss).

George et al. (2025) highlight the measures needed to manage landslide risk in the Western Ghats, noting the importance of land use regulation, the utility of rainfall-based warning systems and the need for community awareness programmes. The Pettimudi landslide shows what happens when such approaches are ignored.

Reference

George, K.A., Sunil, P.S., Anish, A.U. et al. 2025. Landslide Risk Assessment in a Century-Old Tea Plantation Range Following Monsoonal Extremes in the Western Ghats of Kerala, India. Anthropocene Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44177-024-00082-8