If you didn’t know it, the research ship leaving the port of Rimouski in August 2022 appeared to be embarking from the St. Lawrence River on yet another science expedition.

But this voyage was anything but ordinary.

The people on board included artists, social scientists, members of a nearby Indigenous community, and (a few) scientists. Many came from identities that traditionally have been minoritized in the marine sciences. And most had never done anything like this before.

Led by Réseau Québec maritime (RQM), an oceanographic network hosted by the University of Quebec at Rimouski, the Inclusion Mission would take the group northeast along the secluded north shore of the St. Lawrence River and Gulf of St. Lawrence. In the days to come, they’d not only trap sediment, trawl for ocean life, and record the water’s physical and chemical characteristics but also make art and meet with north shore Indigenous communities.

Although the trip constituted only one of the many research cruises worldwide, it built on movements to decolonize science and make discovery accessible to all.

For one of the Inclusion Mission’s attendees, postdoctoral scholar Annie Tamalavage, early feelings of imposter syndrome on the cruise transformed into feelings of belonging by the trip’s end. “It was like a very, very profound experience.”

A Seat at the Table

The goal of the Inclusion Mission, said trip leader Maxence St-Onge, was to break down barriers to seagoing research.

A marine geologist by training, St-Onge conducted a diversity analysis of RQM voyages in early 2021. Despite the organization’s best efforts, the sea expeditions had low diversity, equity, and inclusion of women, racialized minorities, Indigenous Peoples, people with disabilities, and people identifying as LGBTQIA2S+. Trips lacked a variety of fields of study, too.

Many minoritized groups face barriers to participating in research cruises. U.S. oceanographic expeditions between 2000 and 2014 had less than 30% of female chief scientists, according to one study. A quarter of Canadians have a disability, but some geoscientists have said the field sends a message that they aren’t welcome. LGBTQIA2S+ scientists reported in a global survey that they are less open about their identities in the Earth sciences than in other disciplines. And of the 6,720 graduate students in geosciences, atmospheric sciences, and ocean sciences in the United States in 2018, only 860 (about 13%) are people of color.

The Aha Honua declaration asked scientists to create “meaningful partnerships” with Indigenous groups.

Calls to decolonize science have extended to oceangoing research, too. In 2019, the Canadian Indigenous Delegation summoned the ocean-observing community to recognize the Traditional Knowledge of Indigenous Peoples worldwide. The Aha Honua declaration rallied scientists to create “meaningful partnerships” with Indigenous groups and nations.

To target these issues specifically, St-Onge prioritized applicants from minoritized groups or people from nontraditional research disciplines for spots on the cruise. And all participants took training from the Quebec-based, Indigenous-led training group Ashukan on best practices for research with Indigenous communities.

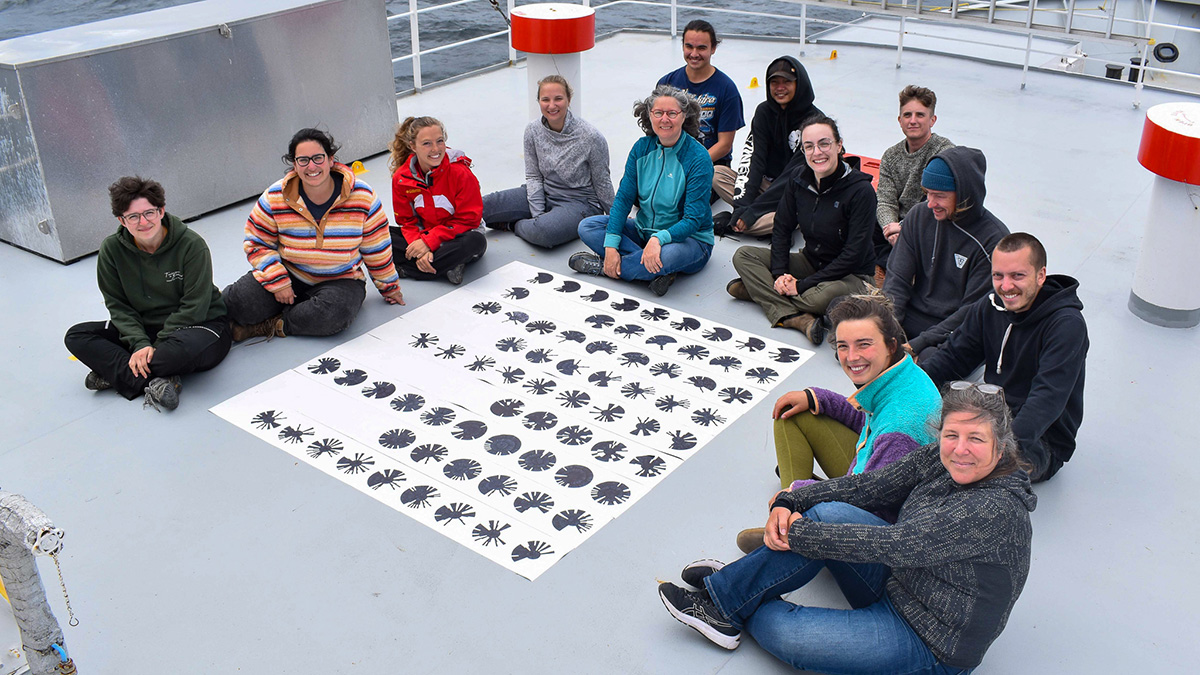

In the end, a little over a dozen people participated in the cruise, and each came with a unique story: An Innu intern had promised himself he’d try something new this year. An architect-turned-artist had always regretted never having studied oceanography. And an early-career paleoclimatologist questioned her future in academia.

William St-Onge: The Richness of the Sea

William St-Onge (no relation to Maxence) worked as an intern for the Territory and Resources sector in his Pessamit community along the St. Lawrence River’s north shore.

When his supervisor told him about the Inclusion Mission, he immediately said yes. He’d promised himself to try new things this year.

On the ship, St-Onge dissected mollusks, released trawl nets, and scooped up sediment in a Van Veen sampler. These new tasks were part of research projects proposed by scientists who’d applied for the voyage. Working hours stretched from 7:00 a.m. to 11:00 p.m.

“There wasn’t much I didn’t like,” said St-Onge. “Discovering all the marine life was stunning. I was clueless about most of it.”

St-Onge also aided a research initiative involving five Indigenous communities and their changing relationship with the St. Lawrence. The research project is led by social scientist Roxane Lavoie from Université Laval in Quebec and seeks to understand how marine vessel traffic along the St. Lawrence River affects Indigenous communities.

During the voyage, Lavoie and others visited villages that could be reached only by boat or plane. Western science disciplines often choose research methods before starting a project, but Lavoie is cocreating the research design with her Indigenous partners.

Danielle Robitaille: A Place for Art

Artist Danielle Robitaille originally planned to study oceanography in college but chose architecture to stay closer to family. Although excited to finally go to sea, Robitaille worried about fitting in.

“I was a little afraid that art processes could be regarded as nonvalid by scientists, but that was not the case at all.”

“I was a little afraid that art processes could be regarded as nonvalid by scientists, but that was not the case at all,” Robitaille said.

Since 2019, Robitaille’s art has mapped her emotions on a daily emotion wheel. The project borrows from data art and procedural art because it involves continually collecting data.

On board, her emotions ranged from overwhelmed joy to energy-sapped fatigue.

It wasn’t long before the experience began shaping her art. She renamed the emotion wheel she’d been filling out since 2019 as a “feelings rosette.” In oceanography, a rosette sampler is an instrument that measures salinity, temperature, and other characteristics of ocean water.

Others on board began filling out feelings rosettes, too. Side by side, the rosettes revealed the emotional landscape of the voyage and the personalities of the people on it.

“The results also show how open or truthful a person can be examining how they are feeling,” Robitaille said.

Annie Tamalavage: Rekindling Passion

For paleoclimatologist Tamalavage, the Inclusion Mission signaled a return to sea voyages driven by curiosity, not just analytical research.

Modern natural science has its roots in early scientific voyages by Europeans seeking knowledge and wealth on distant shores. Charles Darwin penned detailed accounts of his observations as a naturalist on board HMS Beagle from 1831 to 1836. Just decades later, mariners on HMS Challenger laid the foundation of oceanography by sailing the world from 1873 to 1876, taking measurements of temperature, chemistry, and currents.

“I was just so hopeful and reminded [of] why I love this work in the first place.”

“Although we know early exploration has many conflicts related to colonialism and conquest, I have spent time trying to relate myself to these men from a scientific perspective,” said Tamalavage, whose research project for the Inclusion Mission studied carbon transported through the mouth of the Romaine River over time as human industries morphed along its shores.

Deep philosophical pondering about our planet and a desire to explore were goals that connected the Inclusion Mission with historical journeys, said Tamalavage.

The connection was made more potent by bringing together a diverse group.

“There was like a lot of emotion relative to the cruise, like everyone was kind of crying at various times,” Tamalavage said. “When I could get on board and see and feel respected as a woman…I was just so hopeful and reminded [of] why I love this work in the first place.”

Inclusion Mission 2.0?

Last summer, RQM also supported an LGBTQIA2S+ and female-led scientific sailing expedition studying plastics in the St. Lawrence.

As with most research projects, said organizer Maxence St-Onge, funding is the main factor that will decide whether RQM will be able to reiterate and deepen the spirit of the Inclusion Mission in the years to come. “We really hope so.”

—Jenessa Duncombe (@jrdscience), Staff Writer