In 2009, Rolf Hut—then a doctoral student at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands—hacked a $40 Nintendo Wii remote, turning it into a sensor capable of measuring evaporation in a lake.

The innovation, tested in his lab’s wave generator basin, became part of Hut’s doctoral thesis and changed the course of his career. Though he’s now an associate professor at Delft, Hut considers himself a professional tinkerer and a teacher of tinkerers.

Back in 2009, Hut and a group of fellow Ph.D. students organized a session at AGU’s annual meeting in which hydrologists could demonstrate the quirky measurement devices they’d made, hacked, scavenged, or used in a manner entirely different from what manufacturers intended.

The session, “Self-Made Sensors and Unintended Use of Measurement Equipment,” was so popular that Hut organized it again the next year and the next. In addition to Hut’s remodeled Wiimote, early sessions included an acoustic rain sensor made from singing birthday card speakers, a demonstration of how to use a handheld GPS unit to measure tidal slack in estuaries, and a giant temperature-sensing pole that showed how the room heated up after the coffee break.

Since then, the endeavor has grown from a single session to many, expanded to the annual meeting of the European Geosciences Union in addition to AGU’s, and gained a new name: “People just kept calling it ‘the MacGyver session,’” Hut said.

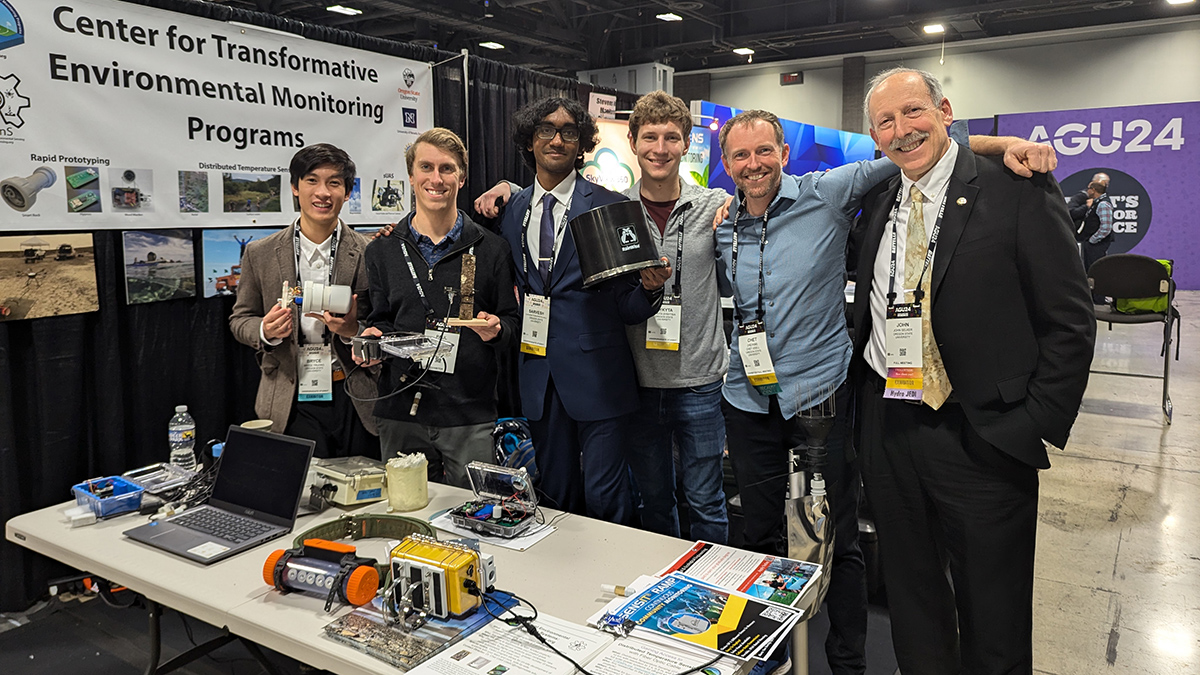

This year, there are five MacGyver sessions, encompassing space weather, ocean environments, the geosphere, and crowdsourced science—the biggest program yet, said Chet Udell of Oregon State University, an electrical engineer and musical composer who is convening the hydrology session.

“The MacGyver sessions are a powder keg of possibilities,” Udell said. “You never know who’s gonna talk with who and what really cool collaboration or initiative could get started that way.”

The MacGyver Spirit

The term “MacGyver” originated with the 1980s television character, a resourceful secret agent known for elegantly solving complex problems with a Swiss Army knife, a few paper clips, chewing gum, or the roll of duct tape he always kept in his back pocket.

That can-do attitude is a natural fit for science, said Udell. “The MacGyver spirit is all about empowering the curiosity that drives science to also drive instrumentation.”

“Oftentimes, [scientists] come up to the barrier of, ‘I can’t ask that question because measuring this thing would be too infeasible, too complicated, too expensive, [the sensor] doesn’t exist,’” he said.

In addition to innovation—“There are a lot of people generating new science because they’ve hacked their instrumentation”—collaboration is key to the MacGyver spirit, Udell said. The ethos is less do-it-yourself (DIY) and more do-it-together. With strong links to the open-source and makerspace traditions, community and transparency are prioritized over competition and secrecy.

“No one lab has all of the expertise, the tools, and the capacity to bring these really interesting, handmade types of DIY innovation to the sciences,” Udell said.

Until recently, the MacGyver sessions were among the only places scientists and engineers could share these kinds of innovations with others. Journal articles’ methods sections typically aren’t long enough to explain exactly how to make one of these hacked or duct-taped devices.

But in 2017, the multidisciplinary, peer-reviewed journal HardwareX was launched with the aim of accelerating the distribution of low-cost, high-quality, open-source scientific hardware. Udell is an associate editor of the journal and recently published an article there with instructions on how to build a “Pied Piper” device that senses pest insects and then lures them into a trap. Citations from HardwareX can help MacGyver scientists justify time spent tinkering, he added.

The Alchemy of Serendipity

The in-person MacGyver sessions remain the heart of the movement, said Udell. There’s a certain alchemy that happens when you bring similarly geeky people together. “You know you’ve really found your community,” said Udell. “There’s a sensation that we’re all cut from the same cloth.”

“We want people to bring the physical device they’ve made and have a nerd-on-nerd discussion about that.”

There’s a reason they’re usually poster sessions, too, added Hut. “We want people to bring the physical device they’ve made and have a nerd-on-nerd discussion about that, which is a very different sort of communication than one-to-many broadcasting your awesome work.”

The format facilitates serendipitous discovery, too. “People walk by and they’re like, ‘Hey, what’s this weird device? I didn’t know you could measure that,’” said Udell. The conversation might spark an epiphany that could help someone solve a problem they’ve been wrestling with in their own research.

Kristina Collins, an electrical engineer who has convened several MacGyver sessions, said scientists and engineers from all disciplines are welcome at any of them—not just those in their own “Hogwarts House” or discipline.

“Having open-source hardware gives people a way to exchange information across different scientific cultures,” she said. “The point of Fall Meeting is to connect with the gestalt of what’s happening at the level of your field and also across fields. I really like that. I think everything interesting happens at the interface.”

Crowdsourced Science

Collins, now a research scientist at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, stumbled upon the MacGyver sessions at her first AGU annual meeting, in 2019—when she was a graduate student and the sessions were hydrology only.

At the time, she was working on making low-cost space weather station receivers for taking Doppler measurements and working with the worldwide ham radio community to deploy them—harnessing low-cost tech and crowdsourced science to gather data from the ionosphere and provide insights into the effects of solar activity on Earth.

“We named [our first receiver] the Grape because people like to name electronics after tiny fruit, and everything else was taken,” she explained (think: kiwis, limes, raspberries, blackberries, apples). “And also, it does its best work in bunches—many, many instruments [working] as a single meta instrument.”

The following year, Collins and some colleagues organized their own MacGyver session on sensors for detecting space weather. At AGU’s Annual Meeting 2025, there will be both oral and poster space weather MacGyver sessions . Collins will present an update on the Personal Space Weather Station Network and the various instruments, including Grape monitors, that make up this distributed, crowdsourced system.

For many geoscientists, the MacGyver spirit is not just a fun side quest, but a fundamental part of the scientific process, said Udell. “The questions we ask and the things that we observe are shaped by what we can measure, and this is shaped by our instrumentation,” he said.

“And so, in a way, what we make ends up making us.”

—Kate Evans (@kategevans.bsky.social), Science Writer