Air pollution levels have dropped dramatically in Spanish cities because of measures adopted by the government to fight the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). These measures include mandatory confinement of the population, reduction of industrial activity, and strict limitations on the use of private vehicles.

Spanish authorities declared a state of emergency and mandatory confinement of the population on 14 March. Schools had been closed 2 days earlier, on 12 March. Two weeks later (on 30 March), amid growing rates of contagion and COVID-19-related deaths, the government enforced the stop of all nonessential industries and activities.

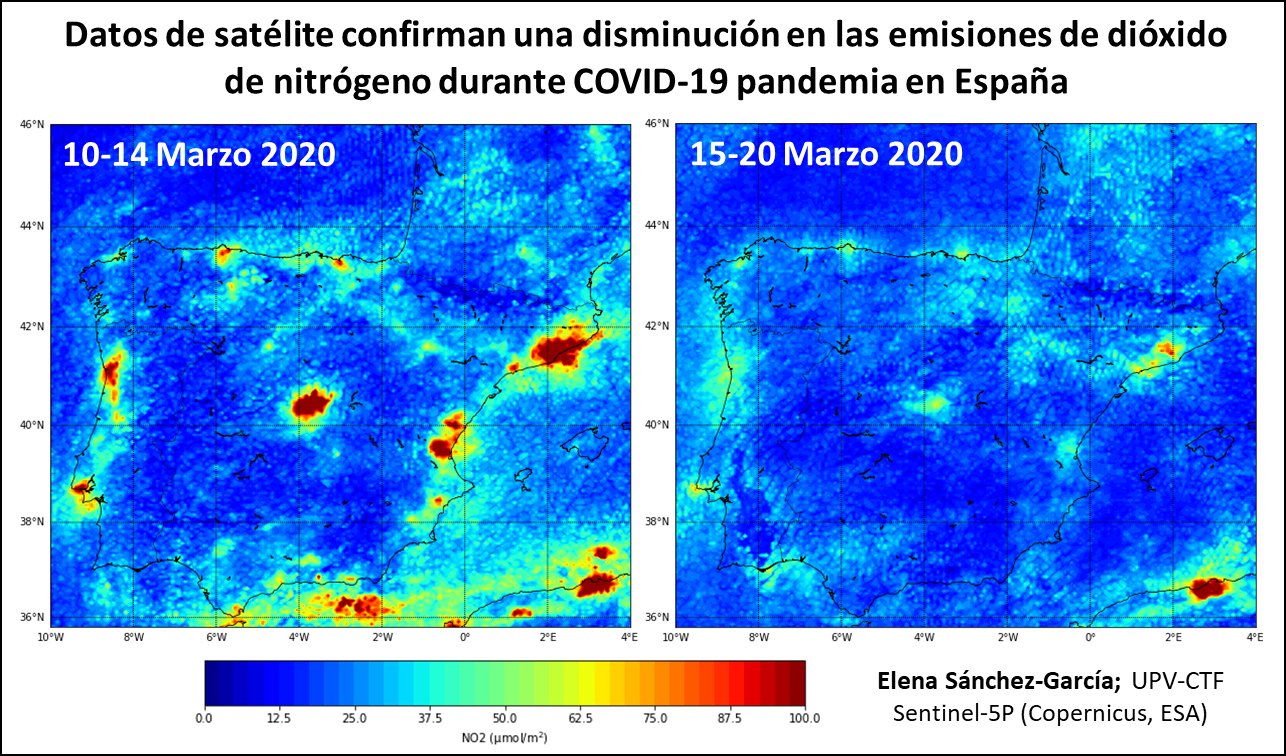

Just a few hours after the declaration of emergency, pollution levels in Spanish cities started to decrease. Within a week, record-low levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) concentrations were measured in the 10 largest cities in the country, with levels averaging 64% lower than in the previous week.

NO2 is routinely monitored in European cities, as it serves as a proxy for traffic pollution. This gas forms in high-temperature combustion in gasoline and diesel vehicles, and its concentrations respond quickly to changes in traffic density. NO2 can cause lung damage and irritate the eyes and respiratory tract. It’s also related to the formation of acid rain.

To track these changes, a team of researchers from Spain’s Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV) analyzed images from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-5P satellite. Launched in 2017, Sentinel has enough resolution to monitor pollution levels at the neighborhood scale. On the basis of these data, the researchers have generated a series of maps that show the concentrations of NO2 in principal Spanish cities.

The satellite data revealed that the highest reduction occurred in Barcelona on 16 March, with NO2 concentrations of 10 micrograms per cubic meter of air, 83% lower than the previous week. Such levels haven’t been recorded in at least 20 years. Barcelona was followed by Castellon (76% lower) and Madrid (73% lower). NO2 levels in Madrid and Barcelona are routinely above 40 micrograms per cubic meter, which is the maximum allowed by environmental regulations in the European Union.

“We were expecting to see similar results to the studies that have been made in China and Italy, but it’s still surprising,” said Elena Sánchez-García, a researcher at UPV and one of the scientists leading the effort to analyze the data of the new study. “These are preliminary results that will be updated in the following weeks.”

A World Without Traffic

Everything points to traffic reduction as the main culprit for the steep reduction in air pollution levels.

Everything points to traffic reduction as the main culprit for the steep drop in air pollution levels. Right after the lockdown started, the number of vehicles on the road declined by 90%. Fuel sales fell 83% for gasoline and 61% for diesel from the previous week, according to the Spanish Ministry of Transport.

The UPV team has also looked at other pollutants, such as carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide, which are also measured by Sentinel-5P, but the reductions aren’t as clear as they are for NO2, likely because other gases stay in the atmosphere for a longer period of time.

The dramatic reduction in atmospheric pollution shows the heavy impact that traffic has on urban air quality. “What we consider is that it’s actually possible to reduce air pollution to a large extent,” said Mark Nieuwenhuijsen, an expert in air pollution and urban planning at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health. “As you can see, if you take an important source [of air pollution] away, air pollution really decreases.”

The air pollution reduction could come as a beneficial side effect in the fight against the novel coronavirus. According to Nieuwenhuijsen, recent evidence points to a slower spread rate in cities with clean air, although the mechanism that produces the correlation is unknown. One possibility is that the viruses could hitch a ride in suspended pollution particles and thus remain in the air for longer periods and spread faster. Another possibility is that air pollution can weaken our natural defenses against infection. For instance, high air pollution levels can damage the lungs, making it easier for the virus to go through the lung’s epithelium.

To help unravel the relationship between the evolution of the pandemic and pollution levels, the European Union Earth Observation Programme has created a website with constantly updated information on pollution levels, maps, and forecasts for 50 major European cities that could be useful to researchers.

Pollution and Risk

The radical measures taken by governments worldwide to protect their populations from the coronavirus are also telling of how human societies respond to other health hazards.

“I think one of the reasons [the coronavirus response has been more immediate] is that with the virus you can see who actually dies, whereas with air pollution it is not so clear; it’s a lot about statistics,” Nieuwenhuijsen said. “We know that in Barcelona, 600 people per year die as a result of air pollution, but you don’t know exactly who the person who died from air pollution is.”

In Barcelona alone, the combination of air pollution and noise caused by traffic prematurely kills more than 1,000 people every year. A long list of health concerns, including child asthma, sleep alterations, mental health issues, cognitive decline in the elderly, and developmental issues in children, are related to traffic. However, they don’t prompt the same kind of swift and costly response that a threat perceived as imminent does.

“I’m hoping that there’s going to be an economic stimulus plan after this, and I hope it will account for the environmental consequences,” Nieuwenhuijsen concluded. “I hope that we are going to do investments in paths that make our society more sustainable, livable, and healthy.”

—Javier Barbuzano (@javibarbuzano), Science Writer

Citation:

Barbuzano, J. (2020), Coronavirus lockdown brings clean air to Spanish cities, Eos, 101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO142570. Published on 09 April 2020.

Text © 2020. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.