“All the indications are that we are at a decisive point in the long history of attempts to mine the deep seabed,” said Michael Lodge, secretary-general of the International Seabed Authority.

The world is “on the threshold of a new industry,” the head of an international body that governs deep-seabed mining said last week. At a 14 November forum in Washington, D. C., Michael Lodge, secretary-general of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), laid out environmental and other challenges to deep-sea mining while maintaining that a new regulatory system could allow the seabed operations to proceed in a sustainable manner. “All the indications are that we are at a decisive point in the long history of attempts to mine the deep seabed,” he said.

Although commercial exploitation of seafloor materials has not yet begun and could be years off, Lodge told the joint meeting of several boards of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) that ISA has approved 29 exploration contracts covering more than 1.3 million square kilometers of the seabed in the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic oceans. He distinguished deep-seabed mining from shallow-water mining for gold, sand, and other materials, which has gone on for centuries. Also, ISA distinguishes between exploration and exploitation activities.

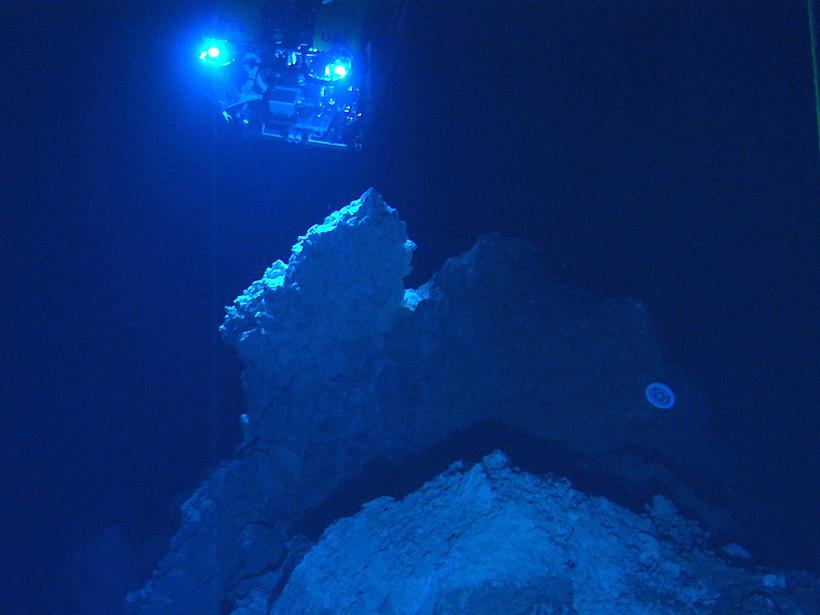

Technology for underwater mining, including remotely operated vehicles and other tools, has advanced enormously during the past few years, Lodge noted. Still to be developed, however, are a regulatory regime for mineral exploitation and reliable ways of knowing if a region of the seabed contains sufficient resources—such as manganese nodules, ferromanganese crusts, massive sulfides, or metal-rich muds—to support major capital investments, he said.

Developing New Regulations

ISA currently is crafting regulations, open for comment until 20 December, on the exploitation of deep-sea mineral resources.

Established under the 1982 United Nations (UN) Convention on the Law of the Sea, ISA oversees mining in the deep sea beyond the exclusive economic zone jurisdictions of individual countries. The organization currently is crafting regulations, open for comment until 20 December, on the exploitation of deep-sea mineral resources. Lodge said that ISA “must develop environmental regulations that ensure that exploration and exploitation take place in a manner that recognizes the need to protect the environment, both on the ocean floor and in the water column.”

Among those submitting comments, the Deep-Sea Minerals Working Group of the Deep-Ocean Stewardship Initiative (DOSI) called the consultative approach to developing ISA’s mining code “commendable” but urged more openness. “Exploitation of the Seabed will affect all nations in perpetuity. A clear, open process to develop these Regulations is necessary,” reads the 16 November comments from DOSI, a network of more than 700 experts from about 40 countries. DOSI’s letter, provided to Eos, also recommends that the regulation preamble reflect language from the UN convention about the need to “ensure effective protection for the marine environment from harmful effects which may arise from such activities.”

At the forum, Conn Nugent, director of the seabed mining project for Pew Charitable Trusts in Washington, D. C., said his group’s goal is to help ensure passage of a mining code that reserves large no-mining areas and adopts a precautionary code to govern activities where mining is allowed.

Environmental Issues

Other speakers in a panel discussion also addressed environmental concerns. “All mining has an impact,” said Mark Hannington, head of the marine mineral resources group at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research. “You’re either impacting society or land-based ecosystems or water quality or you’re affecting ecosystems on the bottom of the ocean.”

He said some mineral deposits should be off limits. “Obviously, the hydrothermal vents that are still active are unique ecosystems, and nobody intends to mine those,” Hannington noted. He said inactive hydrothermal vents might be attractive for mining but are harder to locate, and “we don’t know what kind of ecosystems might be associated with inactive vents.”

Dozens of scientists, however, last month expressed concern about a recent ISA decision to grant a contract for massive sulfide mineral exploration in a region of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge with active vents. “These unique hydrothermal vent sites”—known as Lost City, TAG, and Broken Spur—“are irreplaceable, and their vulnerability to nearby exploration, let alone seabed mining, is entirely unknown,” reads a 27 October letter, provided to Eos, which was signed by Beth Orcutt, senior research scientist with the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay, Maine, and cosigned by nearly 50 other scientists.

“A critical thing is to understand what our environmental goals are. Clearly, there is going to be habitat destruction, so what is it we are trying to protect?”

Cindy Van Dover, professor of biological oceanography at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment in Durham, N.C., and a panelist at the forum, said that it’s “upside down” for exploration contracts to be awarded “before we understand what our regional environmental management plans are.”

Van Dover, who said she is neither pro- nor anti-mining, noted that mining degradation won’t just include “what you scrape up.” She said a sediment plume could affect the benthic and pelagic environment, and sound and light disturbances and toxic heavy metals also could disturb the marine environment. “A critical thing is to understand what our environmental goals are. Clearly, there is going to be habitat destruction, so what is it we are trying to protect?” she said.

Moving Forward

Hannington cautioned that although the number of areas with evidence of some valuable minerals is “astounding,” there is a big difference between a potential mineral resource and just a mineral occurrence. Global mining companies, he observed, currently are on the sidelines and don’t necessarily view deep-seabed mining as something of immediate interest.

Once new regulations governing exploitation are approved, possibly within a few years, mining likely would start slowly at relatively small scales, according to Lodge and others. “I think it will start off with a few operators who are willing to take the risk and invest that capital,” said Lodge. However, at least one expert attending the seafloor mining forum disagreed with that forecast. Larry Meinert, deputy associate director for energy and mineral resources at the U.S. Geological Survey, told Eos that he doesn’t see “a viable way to develop deep-sea mining as an industry.”

“No company could afford to put in a billion dollars of assessment to figure out whether this could be done,” said Meinert, who spoke about minerals at an earlier session of the NASEM meeting. “There’s no economic model that could pay for that.”

—Randy Showstack (@RandyShowstack), Staff Writer

Citation:

Showstack, R. (2017), Deep-seabed mining may come soon, says head of governing group, Eos, 98, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO087489. Published on 22 November 2017.

Text © 2017. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.