On the night of 2 December 1229, the Japanese courtier and poet Fujiwara no Teika watched the Moon emerge above the Kyoto hills. It was partially eclipsed, and as totality approached, the bright disk darkened and seemed to disappear completely.

“The old folk had never seen it like this,” Teika wrote in his diary a few days later. “It was truly something to fear. Indeed, in my seventy years I have never heard of or seen [such a thing].”

Teika’s and others ancient observations of rare dark lunar eclipses have recently taken on new importance after scientists used the records to date notable volcanic eruptions that occurred nearly a thousand years ago. The findings, published in Nature, could help answer some big questions about volcanism and climate change.

“We had no idea that we would find this beautiful text—it was out of pure luck.”

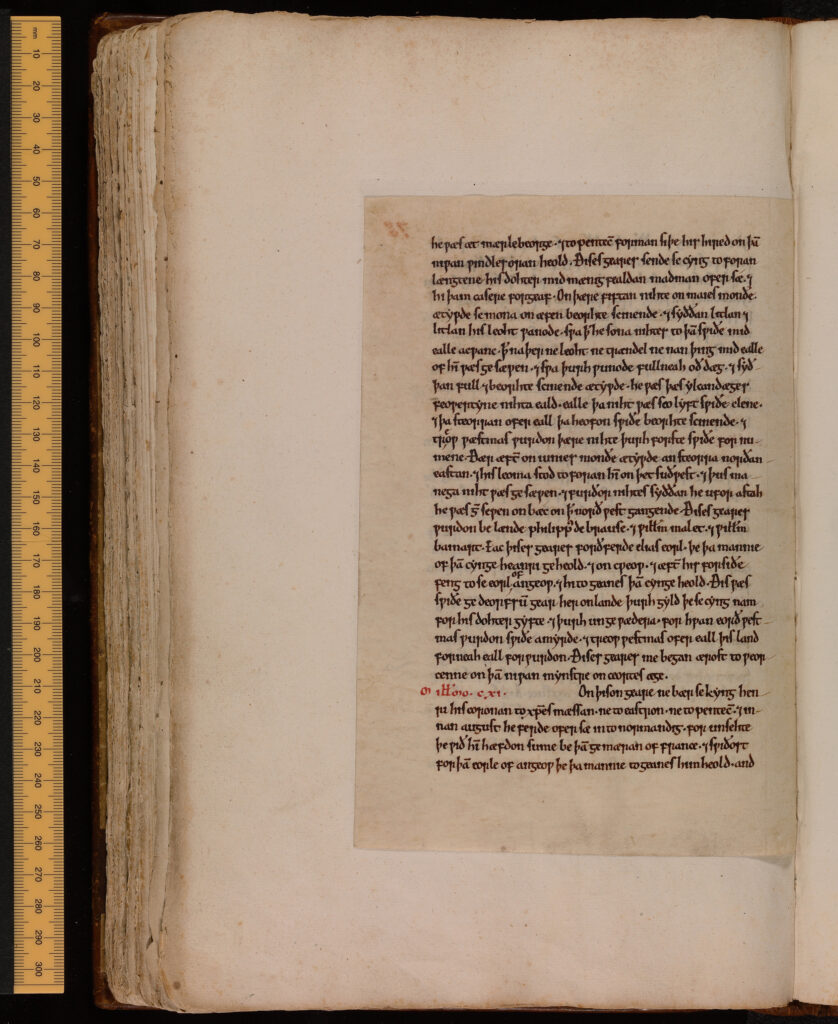

University of Geneva paleoclimatologist Sébastien Guillet first read a translation of Teika’s diary, called the Meigetsuki, during the COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020, and he was thrilled. “We had no idea that we would find this beautiful text—it was out of pure luck.” For years, he had been poring over hundreds of medieval manuscripts, searching for records of lunar eclipses that described the color of the Moon in totality.

If they gave any particulars at all, most of the accounts penned by clerics, monks, crusading soldiers, or urban laymen described a reddish “blood moon” typically seen during a total lunar eclipse on a clear night. A few, however, described eerie dark moons such as the one Teika saw.

The 12th and 13th centuries were among the most volcanically active of the past 2,500 years. Scientists know from telltale sulfate layers in Greenland and Antarctic ice cores that there were seven significant volcanic eruptions between 1108 and 1286. But only one of them—the eruption of Samalas on the island of Lombok in Indonesia in 1257—has been linked to a specific volcano or location.

“These eruptions are very interesting because they happen at a quite critical moment,” Guillet said: the transition from the warm Medieval Climate Anomaly to the much colder Little Ice Age. “Did they contribute to this transition? And if so, to what extent? I don’t think there is a clear consensus among scientists on these questions.”

To determine causation, scientists need precise dating. And though ice cores are invaluable records, the dramatic events they help document can’t confidently be pinned to a specific year. Ice can move around over the centuries, and sections can be lost during the drilling process.

“If you don’t get the date right, even within 1 or 2 years, then it’s quite easy to…attribute something to a volcano that could just be natural variability,” Guillet said. Or you could blame the wrong volcano, added study coauthor Clive Oppenheimer, a volcanologist at the University of Cambridge.

The beauty of eclipses is that we know exactly when they occurred. And crucially, the color of the Moon during totality turns out to be a good proxy for whether there’s been a massive volcanic eruption lately.

Many volcanic eruptions send sulfur gas and particles into the troposphere, but only the largest and most explosive events inject them into the stratosphere, where they are blown around Earth and form sunlight-blocking aerosol veils. These events can temporarily cool the climate—the 1815 Tambora eruption famously caused the 1816 “year without a summer”—and they affect eclipses, too.

In a normal total lunar eclipse, where Earth slides directly between the Sun and Moon, our atmosphere allows just the long red light waves to sneak around the planet and illuminate the lunar surface. But when the stratosphere is crowded with sulfate aerosols, even those ruddy rays are blocked from reaching the Moon’s face, rendering it dark.

From more recent major eruptions such as Krakatau in 1883 and Pinatubo in 1991, scientists know that this eclipse effect lasts about a year.

Records Revealed

In ancient manuscripts from Europe, the Middle East, and East Asia between 1100 and 1300, Guillet and colleagues found hundreds of accounts of total lunar eclipses. Aside from Teika’s diary, none of almost 200 Japanese, Chinese, and Korean sources made any comment on the Moon’s color.

“It’s a new, elegant approach, bringing together all these different lines of evidence.”

But medieval Christians, mostly in Europe, considered a blood-red moon to be a sign of the impending apocalypse, so they were paying particular attention and provided information about the color and brightness of the Moon for 36 eclipses—more than half of those that would have been visible during the period.

Records of dark lunar eclipses showed up in 1110, 1172, 1229, 1258, and 1276, contemporaneous with five of the seven largest volcanic sulfate signals recorded in polar ice cores. (Several records following the other two big eruptions described a typical red moon, leading Guillet and his colleagues to speculate that the plumes of those volcanoes reached only to the troposphere and were perhaps located close to Greenland, resulting in an exaggerated signal.)

The group then cross-referenced the eclipse data with global aerosol simulations, climate models, and summer temperature reconstructions from tree rings to date these five major eruptions to within a few months.

“It’s a new, elegant approach, bringing together all these different lines of evidence,” said Charlotte Pearson, a geoarchaeologist and dendrochronologist at the University of Arizona who was not involved in the study.

Volcanic eruptions and eclipses are anchor points that can help researchers to synchronize the chronologies excavated from different sources, such as ice cores and tree rings, she said. “The more you can put everything onto a single timeline, the better you can explore what these events meant to people.”

Medieval chroniclers recorded not just dark moons, but frosts, crop failures, and famines, she said. The eclipse records help to link these disruptions to large volcanic eruptions. If there is enough volcanic dust in the stratosphere to turn the eclipsing Moon black, there’s likely enough to cool the climate—something scientists can corroborate by checking tree rings for years of poor growth.

“These eclipse data provide a completely independent means to probe the atmospheric spread of the dust from these very large medieval eruptions,” Oppenheimer said. That knowledge may also help scientists to predict the effects of future volcanoes.

—Kate Evans (@kate_g_evans), Science Writer

This news article is included in our ENGAGE resource for educators seeking science news for their classroom lessons. Browse all ENGAGE articles, and share with your fellow educators how you integrated the article into an activity in the comments section below.