Fire rained from the sky. Avalanches coursed down a collapsing mountain. An island kingdom perished. These apocalyptic scenes likely describe the 1257 eruption of Samalas—the most explosive volcano you’ve never heard of—if historic records from the Indonesian island of Lombok are true.

In a new study, Panthéon-Sorbonne University doctoral student and geomorphologist Mukhamad Malawani and his colleagues used locally preserved historic records called babad to reconstruct what Lombok may have been like before, during, and after the Samalas eruption. Investigating the changes wrought by this catastrophe may help scientists understand ancient evacuation processes, posteruption recovery, and societal resilience.

Paradise Lost

Lombok is nestled between the islands of Bali to the west and Sumbawa to the east. These islands form part of the volcano-studded Indonesian arc, largely the product of subduction as the Australian tectonic plate’s northwestern oceanic edge dives below the Sunda plate. The Rinjani volcanic complex, crowned by a lake-filled caldera left by the Samalas eruption, reigns over Lombok’s landscape, according to Céline Vidal, a volcanologist at the University of Cambridge. During the past 10,000 years, large eruptions have punctuated Rinjani’s history, with the 1257 event ranking among the most explosive in recent times, said Vidal, who has worked on Samalas but was not involved in this study.

Like avalanches, these flows “destroy[ed] everything in their way.”

After the eruption, the island morphed from a lush paradise into a dry, ash-covered landscape, according to study coauthor Franck Lavigne, a geographer at Panthéon-Sorbonne University who has worked on the Samalas eruption for the past decade.

Prior studies of the meters- to tens-of-meters-thick deposits expelled from the volcano helped scientists such as Vidal reconstruct the eruption itself. Ash, pumice, and gas rose into the atmosphere as the eruption began. The cloud spread horizontally, raining ash and pumice onto, and even beyond, the island. Once the gas sustaining the plume was exhausted, the towering column collapsed, forming clouds of hot gas, ash, and other debris produced by the eruption that flowed along the ground, rapidly traversing the landscape.

Like avalanches, these flows “destroy[ed] everything in their way,” Vidal said. Soon after, mud flows called lahars, caused when rain follows such an eruption, capped the volcanic deposits, she said.

The Babad

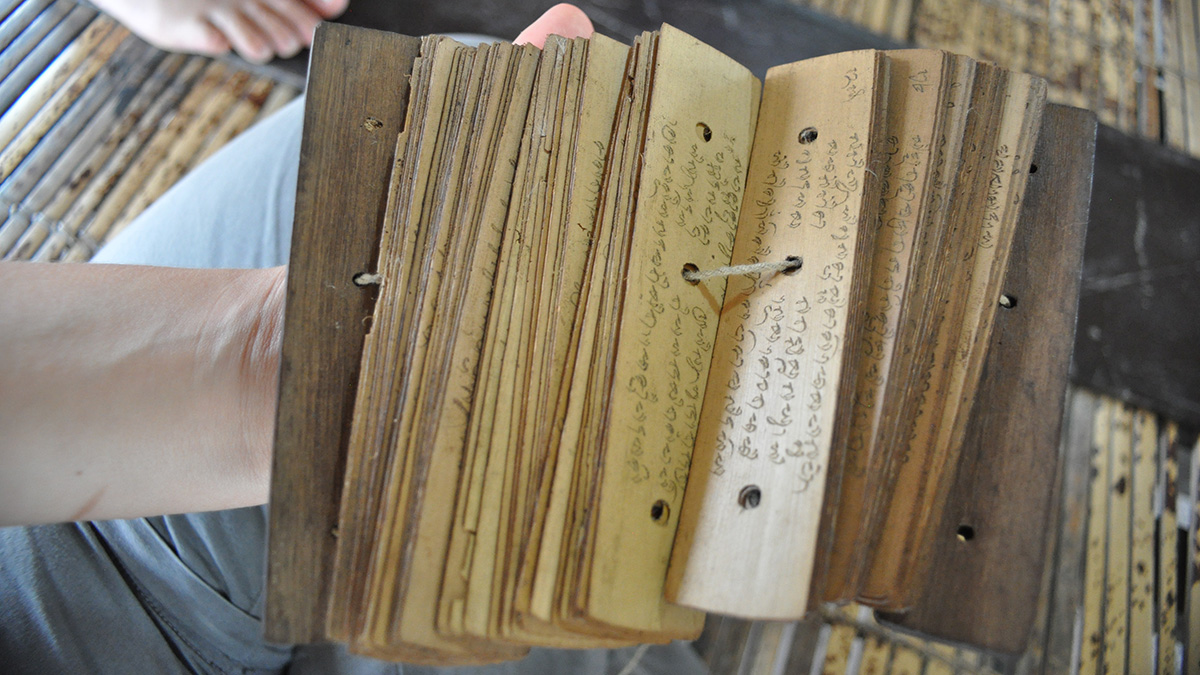

The babad examined in this study are written collections of oral traditions often transcribed in an Old Javanese script that few people can read. The sacred texts contain a mixture of legend and fact, said Lavigne. The reason is partly because oral traditions change as cultures do. The babad examined in this study were likely compiled in the 18th or 19th century—several centuries after the Samalas eruption.

The researchers focused on three babad. Babad Lombok had already been translated to modern Javanese and Indonesian and resides at the Museum of Nusa Tenggara Barat. Babad Suwung, also property of the museum, had yet to be translated from Old Javanese, so Lavigne and colleagues arranged for a translation to occur in a village where the person reading the babad sang from the palm leaves in a ceremony attended by all the residents. The third, Babad Sembalun, is familiar only to people who live in the Sembalun Valley on the northeastern flank of Samalas, where the original palm leaves remain.

With the translations, Malawani and Lavigne and their colleagues examined the three babad for any information pertaining to an eruption. Because the babad provide no absolute time constraints for the Samalas eruption, the researchers had to verify that these records truly describe the event. To do so, they relied on comparisons. For instance, Babad Lombok specifically mentions the Old Javanese word for pumice, which helped to confirm the link between the babads’ descriptions and the Samalas eruption. “We know that it’s this eruption because it’s the only [recent] eruption that produced pumice,” said Lavigne. “What we see in the field corresponds to the descriptions in the babad.”

In that context, Babad Lombok and Babad Sembalun describe the collapse of Mount Rinjani, along with debris flows and avalanches. Babad Suwung, which includes the story of a group that journeyed to the nearby island of Sumbawa just before the eruption, describes “fire-rain” and burning winds—likely a surge of hot gas and ash—that seared the village across the strait.

Before and After

Babad Lombok mentions a lost kingdom, Pamatan, in a lowland, coastal area, said Lavigne. With a bustling population of 10,000, the supposed city boasted infrastructure, agriculture, fishing, and commerce but was wiped out by an eruption, according to the text. If Pamatan exists below Samalas’s volcanic deposits, nobody knows where it lies, he said, though they have some educated guesses. Pumice quarries dot the island, trenched in deposits that can be as thick as 50 meters. Though no settlement has been found, Lavigne said he hopes that houses or temples might be unearthed in the future.

To extract what happened to the island’s inhabitants after the eruption, Malawani, Lavigne, and colleagues traced the paths of refugees by matching place-names listed in the babad with modern geography, as well as names taken from colonial-era maps. However, these paths could be describing either immediate evacuation or later migration, said Lavigne. “It’s not always clear.”

Resilience meant resettlement away from the pumice-coated plains.

Babad Lombok also records which leaders built new settlements. For example, important people of Pamatan, such as the governor, harbormaster, headman, and royal family, each oversaw construction of a new village. On Lombok, resilience meant resettlement away from the pumice-coated plains, said Lavigne.

Timelines

For the past few decades, knowledge of volcanic eruptions in general has come from detailed studies of volcanic deposits and monitoring of those sites, said Agung Harijoko, a volcanologist at Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, who was not involved with this study. Historical records, such as those described in the new study, may provide additional information about past eruptions and mitigation efforts that’s otherwise hard to find.

In particular, said Vidal, little-studied oral histories, common in Indigenous cultures, contain invaluable information. “This study was remarkable,” she said, because it uses local records, initially transmitted orally, after much of Lombok was destroyed.

However, because the babad do not include dates, reconstructing timelines is tricky. “Impacts immediately after an event are different from the long-term impacts, and people’s understanding of that impact changes with time,” said volcanologist Amanda Clarke, a professor at Arizona State University who was not involved with the study.

For instance, how long the recovery took is not mentioned in any documents from Lombok, said Malawani, who is also a lecturer at Gadjah Mada University. Fortunately, another document from Java, the Deśavarṇana, helped the researchers bracket the recovery efforts to about a century.

Many babad still need to be translated and studied, said Lavigne. “Some of them still may have some interesting information.”

—Alka Tripathy-Lang (@DrAlkaTrip), Science Writer