A presumed pause in the rise of Earth’s average global surface temperature might never have happened, according to new research published this week. Instead, the apparent hiatus, first reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2013, resulted from a shift during the last couple of decades to greater use of buoys for measuring sea surface temperatures. Buoys tend to give cooler readings than measurements taken from ships, explained Thomas Karl, director of the National Centers for Environmental Information of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and lead author on the research paper. Uncorrected, those discrepancies led to the apparent slowdown since 1998 in the long-observed rise of Earth’s average surface temperature.

Global warming over the past 15 years is the strongest it’s been since the latter half of the 20th century.

“The biggest takeaway is that there is no slowdown in global warming,” Karl said. Global warming over the past 15 years is the strongest it’s been since the latter half of the 20th century, he added.

Measurement Bias

To measure how Earth’s average global temperature is changing, scientists combine hundreds of thousands of measurements from Earth’s surface, taken by land instruments, ships, buoys, and orbiting satellites. Scientists must comb through these data to eliminate random errors and correct for differences in how each type of instrument measures temperature.

In a new paper published Thursday in Science, Karl and his colleagues report that they dug into NOAA’s global surface temperature analysis to examine how sea surface temperatures (SSTs) were being measured. Scientists measure SSTs in several ways—by collecting ocean water in a bucket and measuring its temperature directly, measuring the temperature of water taken in by a ship’s engine as a coolant, or using floating buoys moored at locations scattered around the planet’s oceans.

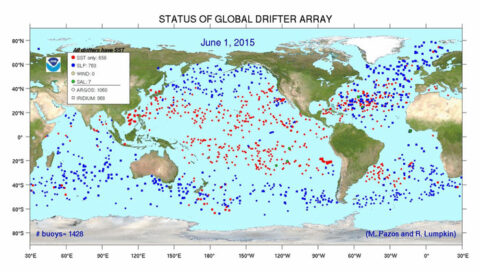

Each technique records slightly different temperatures in the same region, so scientists have to adjust the data. In the last couple of decades, the number of buoys has increased, Karl explained, adding coverage to 15% more of the ocean. Because buoys tend to read colder temperatures than do ships in the same places, Karl and his team corrected for this bias by adding 0.12°C to each buoy measurement.

By combining the ocean data with improved calculations of air temperatures over land around the world, Karl and his colleagues found that overall global surface warming during 2000–2014 was 0.116°C per decade, more than twice the estimated 0.039°C per decade, starting in 1998, that IPCC had reported. Further, having reexamined global temperatures as far back as 1880, Karl and his team found that from 1950 to 1999, the rate of warming was 0.113°C per decade.

“The [new] data still show somewhat slower warming post-2000 than in the preceding decades, but the difference is no longer statistically significant, which means it is no longer justifiable to say that there was a ‘hiatus,’” said Steven Sherwood, director of the Climate Change Research Centre at the University of South Wales, Australia. He was not involved in the study.

“The fact that such small changes to the analysis make the difference between a hiatus or not merely underlines how fragile a concept [the hiatus] was in the first place,” said Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City.

Faux Pause?

Since the IPCC report came out, scientists have been investigating what was causing the supposed hiatus. Some studies found evidence that the leveling of global temperature rise resulted from absorption of the “missing” heat by the world’s oceans.

Other research indicated that although there was no pause in global temperature rise, there might have been a temporary slowdown of warming for the Northern Hemisphere. Michael Mann, director of the Earth System Science Center at Pennsylvania State University, and his colleagues found earlier this year that natural fluctuations in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans led to cooling of the tropical Pacific, driving down average temperatures for the northern half of the globe. Mann calls this phenomenon a “faux pause.”

Even as perceptions of a global warming pause remained widespread, some scientists were finding evidence to the contrary.

”The slowdown, which appears to relate to internal oscillations with an origin on the tropical Pacific, primarily impacts Northern Hemisphere mean temperature and is barely evident in global mean temperature,” Mann told Eos.

Even as perceptions of a global warming pause remained widespread, some scientists were finding evidence to the contrary. A paper in Nature Climate Change last year reported that there was “no pause” in heat extremes around the world. What’s more, NOAA concluded that 2014 was the planet’s hottest year on record.

According to the new analysis, Karl said, global average temperature rise between the years 2000 and 2014 is virtually indistinguishable from that which occurred over the latter half of the 20th century.

—JoAnna Wendel, Staff Writer

Citation: Wendel, J. (2015), Global warming “hiatus” never happened, study says, Eos, 96, doi:10.1029/2015EO031147. Published on 5 June 2015.

Text © 2015. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.