At several points in the past half million years, the Arabian Peninsula—a vast desert today—was dotted with grasslands, rivers, and even a population of water-loving hippos. This humid climate triggered “pulses of occupation,” according to a recent paleoclimate study published in Nature, as early humans settled along the shores of the ancient lakes. Whenever the land was wet, humans migrated in.

“These lakes are opening up a whole new window on our past.”

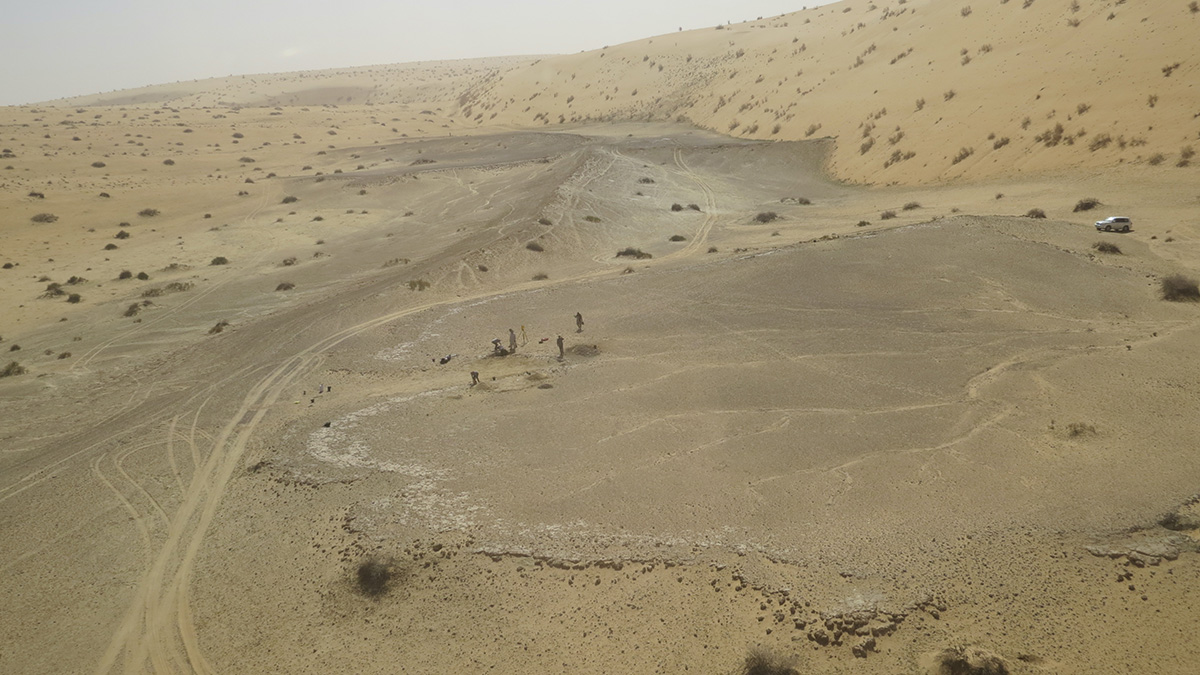

The new study combines geologic dating, fossil records, and archaeological evidence to trace the history of human occupation in the region, specifically at a basin in the Nefud desert called Khall Amayshan. The site has hosted several ancient lakes in the past 400,000 years, each with a unique record of ancient technology.

“It’s only on this one spot where we have the sequence of ecosystems and the sequence of archaeology,” said Michael Petraglia, an archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History who has worked in the region for the past 10 years with the Palaeodeserts Project group. By excavating near the ancient lakes, archaeologists can explore how the cycle of green Arabia and dry Arabia helped humans disperse around the world.

“These lakes are opening up a whole new window on our past,” said Petraglia.

A Stack of Ancient Lake Pancakes

Until recently, archaeology in the region has concentrated on the caves of the eastern Mediterranean while overlooking the nearby desert. Work from the Palaeodeserts group showed that the desert was also a key region for human migration out of Africa.

Satellite imagery helped narrow the search for evidence in the arid Arabian Peninsula. A Palaeodeserts doctoral student used overhead images to identify the possible outlines of 10,000 ancient lakes in the region.

So far, Khall Amayshan is the only site where five ancient lakes have overlapped. “Imagine a stack of pancakes that has fallen over,” Petraglia said of the lake outlines. Whenever the lakes dried up, a conveyor belt of migrating sand dunes covered the area, preventing erosion of lake borders and keeping each distinct lake assemblage intact.

The researchers dated the overlapping lakes to several distinct periods: 400,000; 300,000; 200,000; 130,000–75,000; and 55,000 years ago. These wetter intervals acted like an “engine,” Petraglia said, with “lakes turning on and turning off.” When the lakes were on, plant and animal life proliferated and human hunter-gatherers moved in. Excavations confirmed this outcome, turning up the bones of sizable animals like hippos and early horses, as well as stone tools.

Researchers used luminescence dating to identify the age of each lake. The method measures the rate of absorbed radiation in sand and can identify when a single grain was last exposed to sunlight. Using visible and infrared light, researchers can date quartz to the past 250,000 years and feldspar to the past half million years, respectively. That’s limited for geology research but useful in archaeology.

“The last 1 million years is crucial for human evolution,” explained Bo Li, an associate professor at the University of Wollongong’s Centre for Archaeological Science not involved in the research.

“It’s very rare to have several continuous layers contain different assemblages from the same site,” Li said of Khall Amayshan. “This kind of work can add significantly to our understanding of how humans can migrate between continents [and] utilize the humid conditions in this region.”

Hand Axe History

Stone tools excavated at the site expand the map of human migration routes. The earliest tools, dated to 400,000 years ago, are now the oldest on the Arabian Peninsula and are similar to those used elsewhere by Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis. The most recent lake assemblage, 55,000 years old, could be Neanderthal. If that’s true, it would be the southernmost recorded movement of Neanderthals.

The results indicated that human migration wasn’t just out of Africa. “This is a crossroads, it’s not one direction,” said Petraglia. Continuous research could turn up fossils that connect the migration routes. “We have their tool kits but not their fossils,” he said.

With thousands of lakes to excavate, there’s likely more evidence of migration buried under the sands. The Palaeodeserts group has excavated only a few hundred lake targets so far, but 70% of those excavations have produced archaeological material.

“The discoveries in Khall Amayshan and other sites in the Nefud and beyond are just the tip of the sand dune.”

“Historically, Arabia’s role in prehistory was put in the shadow in spite of its central geographical location in relation to Africa,” said Abdullah Alsharekh, an archaeologist at King Saud University and a coauthor of the paper. “The discoveries in Khall Amayshan and other sites in the Nefud and beyond are just the tip of the sand dune, and I believe there are more impressive discoveries to be unfolded in the near future.”

As archaeologists uncover more sites in the understudied region, they’ll create a clearer picture of paleoclimate and its role in early humans’ march across the continents.

“Knowledge is cumulative, and with more research we have no doubt that the record will show the bigger role Arabia played than previously thought,” said Alsharekh.

—J. Besl (@J_Besl), Science Writer