See more Eos coverage of the California power outages to learn about science’s flickering future.

The same week that scientists at the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California (UC), Berkeley planned to launch a satellite with NASA, lab director Steve Beckwith got news that the power might go out.

California was in the midst of its fall fire season, and the utility that delivers power to UC Berkeley’s campus, Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E), feared that high winds, hot air, and dated equipment could spark a fire. Just in case, the utility sent out word: They’d preemptively cut power to 800,000 customers the following day, Wednesday, 9 October 2019. The outage would be the largest in the state’s history.

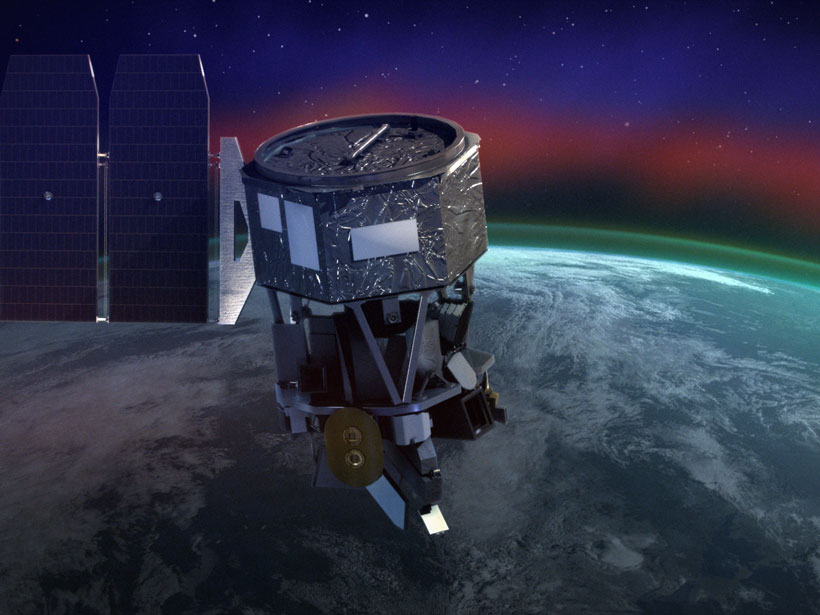

Beckwith knew his team had a problem. The spacecraft carrying the Ionospheric Connection Explorer (ICON) satellite was scheduled to launch from Cape Canaveral, Fla., that week, and Beckwith’s lab needed to be online to act as mission control when the spacecraft deployed the instrument in orbit. To do that, they’d need not only power but also a viable source of backup power. “At first, I didn’t think we could do it,” Beckwith said.

Low-tech infrastructure, long transmission lines, limited personnel, and a myriad of other problems have left PG&E vulnerable.

The power shutoffs were a Hail Mary from a utility plagued by a laundry list of safety issues. PG&E provides power to 16 million household customers across central and Northern California, but its low-tech infrastructure, long transmission lines, limited personnel, and a myriad of other problems have left it vulnerable. The investor-owned utility sparked the Camp Fire in 2018, which left 85 dead and destroyed the town of Paradise. In January 2019, a judge suggested the utility preemptively cut power to customers during high winds as a stopgap effort while the company fixes its larger, more systematic safety concerns.

Ten months later, California residents in 34 counties felt the consequences when the utility shut off power. Those living or working in the footprint of PG&E’s grid had to answer new questions about how to be resilient: How long could they go without power? What backup power did they have? Beckwith needed something more concrete: extension cords. High-capacity, heavy-duty, 50- to 100-foot (15- to 30-meter) extensions cords. And he needed them immediately.

Time to Improvise

The Space Sciences Laboratory sits on a hill in the Silver Lab Addition Building, on the northeastern corner of UC Berkeley’s main campus. The lab had emergency power outlets, located in each floor’s clean rooms. The trick would be connecting the emergency outlets with workstations in the building’s library, where scientists would crunch numbers in real time as the satellite made its first pass over California. After dropping about a thousand dollars on extension cords from Home Depot, Beckwith said, they had the library powered.

The team lined up a contact in San Jose with a truckload of diesel fuel ready to drive their way at a moment’s notice.

The next step was determining where the power would come from. The team had one backup generator, but they ordered a second and lined up a contact in San Jose with a truckload of diesel fuel ready to drive their way at a moment’s notice. “We were confident we could pull it off on generators if we had to,” Beckwith said. But they had another option, a backup power source that could become a lifeline for UC Berkeley in years to come: the school’s cogeneration plant.

Originally a boiler plant to send steam to the campus’s buildings, the university expanded the plant to burn natural gas for electricity. The plant operates around the clock but can supply only part of the campus’s electricity demand.

Fortunately for Beckwith’s team, the Space Sciences Laboratory was on the shortlist of emergency labs that stayed on power. Once PG&E shut off power on Wednesday night—after delaying much of the day—the campus’s cogeneration plant picked up the slack.

As the makeshift mission control at the Space Sciences Laboratory counted down to deployment on Thursday night, fueled by Costco snacks and 400-gallon water tanks, the team could rest easy with two sources of power to rely on: the cogeneration plant and their extra generators. Under a watchful team of electricians, “we were able to acquire the satellite that night and verify [its] health and safety,” said Beckwith.

Pulling off the launch was “like watching a choreographed performance turn into a jazz improvisation as problems came up and the individual team members solved them in real time feeding off one another’s talent and energy,” said Beckwith.

Future Questions

The launch’s success relied in part on the campus’s cogeneration plant, which has an uncertain future.

University chancellor Carol Christ said at a graduate student assembly meeting in 2019 that the aging facility needs to be replaced in the next 10 years. PG&E has said the power shutoffs are likely to occur over that time period.

In addition, the cogeneration plant burns natural gas, and the University of California system is just 5 years away from reaching its sustainability pledge of carbon neutrality.

The sustainability plan, announced in 2013, declares that UC buildings and vehicles must have net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2025. Presently, three quarters of UC Berkeley’s emissions come from powering the campus’s buildings, according to the university’s Office of Sustainability. For the university to reach carbon-neutral levels, it would need to reduce total emissions by 80%.

Replacing natural gas is the “hardest nut to crack to achieve carbon neutrality.”

Replacements for natural gas are expensive and hard to come by. As E&E News reported, the university’s sustainability director, Matthew St. Clair, called replacing natural gas the “hardest nut to crack to achieve carbon neutrality.”

UC Berkeley spokesperson Janet Gilmore said that the university has convened a task force for addressing future power shutoffs. UC Berkeley declined to comment on long-term plans for the cogeneration plant or the impacts of burning natural gas on the 2025 carbon-neutral pledge.

Beckwith said that for his team, the experience made them more resilient. “If we had another blackout,” he said, “I don’t think [working through it is] going to take an enormous effort on my part.”

As to the launch? “We never had a power glitch,” Beckwith said.

—Jenessa Duncombe (@jrdscience), News Writing and Production Fellow

See more Eos coverage of the California power outages to learn about science’s flickering future.

Citation:

Duncombe, J. (2020), How to launch a satellite during a blackout, Eos, 101, . Published on 29 January 2020.

Text © 2020. AGU. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.