A translation of this article was made possible by a partnership with Planeteando. Una traducción de este artículo fue posible gracias a una asociación con Planeteando.

The article also may be read in Portuguese.

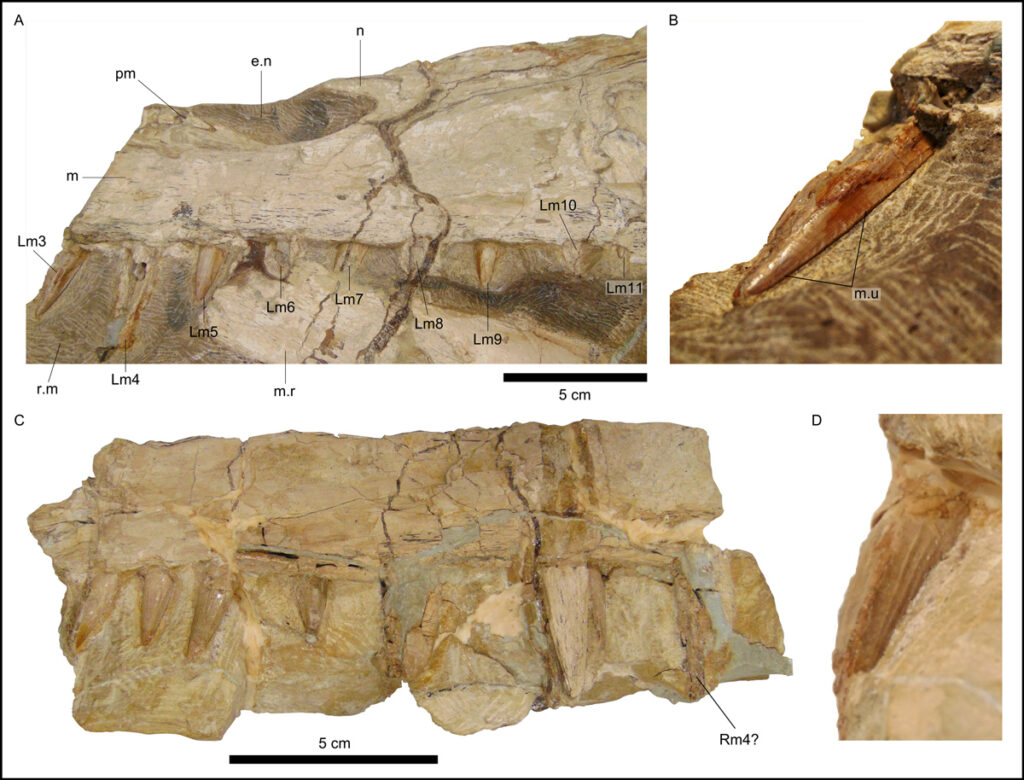

In 1995, British paleontologist David Martill and his German colleague Eberhard “Dino” Frey looked closely at the skull of a 110-million-year-old dinosaur fossil found in northern Brazil. They noticed something curious. A computerized tomography (CT) scan revealed the animal’s snout had been elongated by fossil dealers, presumably to fetch a better price.

Irritated with the situation, Martill and Frey named the new species Irritator challengeri.

But frustration with the fossil, now part of the collection of Germany’s State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, didn’t stop there.

“Unfortunately, there is this general impression that the countries from the Global South are some sort of an amusement park for researchers from the North.”

Today, more than 2,000 paleontologists and other supporters have signed an open letter requesting the fossil’s repatriation to Brazil. This week, they sent the letter to Petra Olschowski, the minister of science, research and arts for the state of Baden-Württemberg, where the museum is located.

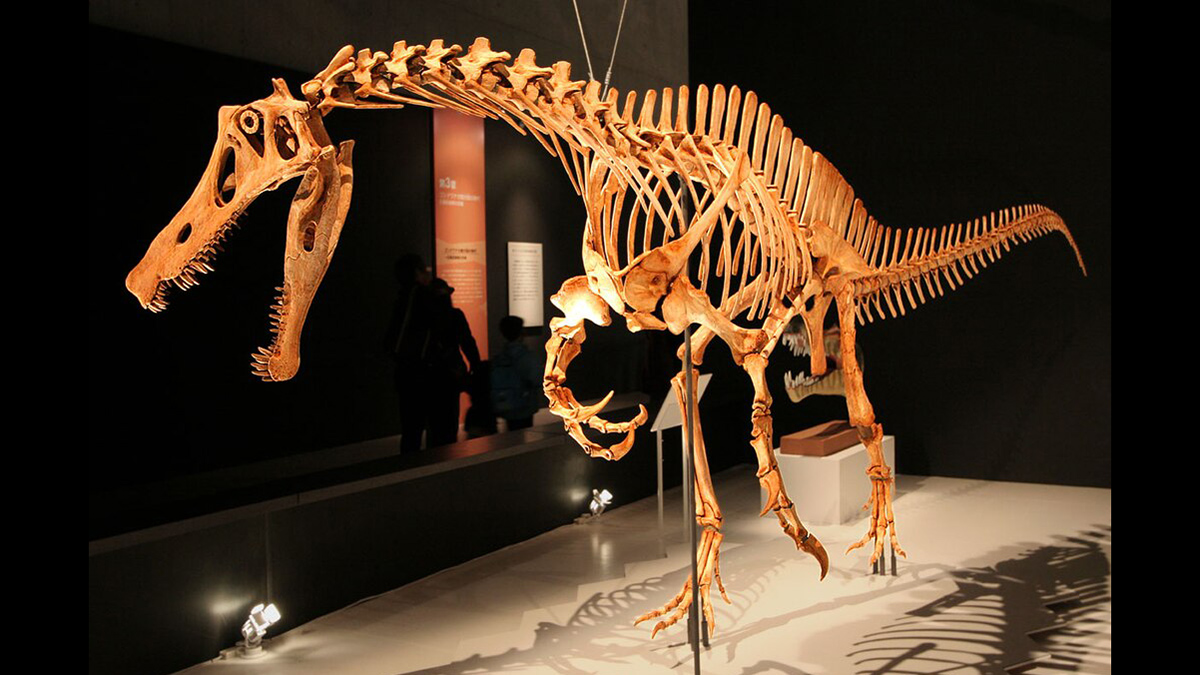

“The Irritator is one of the most important fossils from Brazil because it is the best-preserved skeleton of a rare group of dinosaurs worldwide,” said Aline Ghilardi, a paleontologist at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, who is helping to lead the repatriation effort.

The repatriation request is based on Brazilian legislation enacted in 1942 declaring that fossils found in the country are the state’s property and cannot be traded or exported without authorization. A 1990 law also mandates that any holotype (a fossil representing a new species) remain in the country.

“Basically, we want the Brazilian law to be respected,” Ghilardi said. “Unfortunately, there is this general impression that the countries from the Global South are some sort of an amusement park for researchers from the North who can come here, take our fossils, and put them in their museums to get academic prestige. This is neocolonialism.”

Ethical Statement

Irritator got the attention of academia in May of this year after a new analysis of the skull was published in Palaeontologia Electronica.

The publication contained an ethical statement acknowledging “the possibly problematic status” of the fossil, raising significant criticism about how the museum acquired it. According to the authors, a German dealer likely purchased the fossil from local collectors and took it out of Brazil before 1990. The museum bought the specimen from the dealer in 1991.

The study’s lead author, paleontologist Serjoscha Evers at the University of Fribourg, wrote in an email to Eos that he recognized that he and his colleagues did “a poor job on the statement,” calling it an ethics statement, when, according to him, the issue with the fossil is instead a legal claim.

“Just because a fossil is in a museum and thus available for study, it is not always fair or ethical to work on it.”

Evers, who has signed the letter supporting the Irritator repatriation, decided to halt his work on other Brazilian fossils until there is legal clarification about their origin or unless the research is done under the leadership of a Brazilian colleague.

“I am more aware of provenance issues than before—just because a fossil is in a museum and thus available for study, it is not always fair or ethical to work on it,” Evers wrote. “I think that everything shown to be illegal should, of course, be returned.”

Evers’s paper on the Irritator was taken down for 2 days while Palaeontologia Electronica assessed the matter. The journal’s editor, Matúš Hyžný, wrote in an email to Eos that the journal’s editorial board decided to keep the article available as they found no wrongdoing from the authors.

Michael Rasser, deputy head of the Department of Paleontology of the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, wrote in an email that the institution “takes the open letter and the demand for the return of the fossil seriously” and is working with the Ministry of Science, Research and Arts of Baden-Württemberg to clarify all facts and reach a legal assessment.

Not an Isolated Case

The Irritator case follows a successful campaign from paleontologists in Latin America who requested another German museum in Baden-Württemberg return the fossil of another dinosaur to Brazil. The Ubirajara jubatus fossil left the country illegally sometime between the 1990s and 2000s and was described by Martill and Frey in a 2020 paper in Cretaceous Research.

In June, the Ubirajara fossil became the first dinosaur fossil to be repatriated to Brazil. Editors retracted the Cretaceous Research paper, and the director of the State Museum of Natural History Karlsruhe, where the fossil was held, resigned.

“These cases are not isolated, but the consequence of a systematic scientific colonialism that persists in the field of paleontology to this day.”

“These cases are not isolated, but the consequence of a systematic scientific colonialism that persists in the field of paleontology to this day,” said Juan Cisneros, a paleontologist at the Federal University of Piauí, Brazil, and one of the leaders of the repatriation campaigns.

In a 2022 study, Cisneros, Ghilardi, and colleagues analyzed all published research on new fossil species from two important geological formations in northeastern Brazil and Mexico in the past 3 decades and found that 80% of them did not disclaim whether the authors had permission to collect or export the specimens, a statement requested by both nations. In the Brazilian case, about 90% of the specimens were described by foreign researchers, even though the country prohibits the export of holotypes.

Currently, Ghilardi and her colleagues are compiling a list of more than 500 holotype fossils in museums in Germany, Japan, and the United States that may have been illegally taken from Brazil.

Recognizing the issue, paleontological societies in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru formed a consortium to work together in future repatriation cases and help fight scientific colonialism. One of their first actions was publishing an article in PaleoAmerica suggesting journals require authors to disclose the origin of fossils and include fossil permits in the “materials and methods” sections of academic papers.

“Journals have an important role in blocking scientific colonialism,” said Herminio Araújo Júnior, president of the Brazilian Society of Paleontology.

Martill, a paleontologist at the University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom, said museums are justified in buying pieces from sellers who acquired them illegally if the purchase helps preserve the fossil for academic study. “All paleontologists all over the world should be grateful to curators because they bought those fossils and stopped them from going into private collections where they are available to nobody,” he said.

Martill has criticized national laws, such as Brazil’s, that don’t allow such sales. Still, he said he supports the repatriation of the Irritator fossil.

The return of fossils is more than just a legal issue, Ghilardi said; it is also an ethical imperative. Repatriation can help socioeconomically disadvantaged communities in the Global South.

“It is also a cultural violence to take these fossils from these people,” Ghilardi explained. She hopes the return of the Irritator fossil to Brazil’s Araripe region, where it was found, will help foster the local economy via paleontological tourism and inspire a new generation of scientists. “Through fossils, we can transform a place.”

—Sofia Moutinho (@sofiamoutinhoBR), Science Writer

This news article is included in our ENGAGE resource for educators seeking science news for their classroom lessons. Browse all ENGAGE articles, and share with your fellow educators how you integrated the article into an activity in the comments section below.