Around 5 years ago, Capt. Joey Angnatok, an Inuit fisher and researcher, lowered his fishing nets from his boat, FV What’s Happening, into the Labrador Sea near Makkovik, a town in eastern Canada. Seafloor data suggested that the ocean should be 700 meters deep. But when he let out that much net, he still had several hundred meters of slack floating on the surface, indicating the nets had hit bottom earlier than expected. As he tried to reel the nets back in, they got snagged.

“We ruined, I think, six or seven nets,” Angnatok said.

Wanting to protect his gear in the future, Angnatok said he wrote “Don’t ever come back here again” in his notebook.

Not long afterward, however, Angnatok’s colleague David Cote, an ecologist at Fisheries and Oceans Canada who was searching for unknown areas of marine biodiversity, asked him whether he’d come across anything interesting recently. Angnatok is often consulted on research projects, because as a lifelong fisherman who has been collecting climate data with researchers and fellow Inuit for more than 30 years, he has a strong knowledge of the sea bottom. “Over the years, you have a little dictionary in your head of what certain places look like,” he said. Angnatok told Cote what happened with his nets, and the pair suspected coral might have been the culprit.

That event, combined with other local ecological knowledge, spurred the discovery of an unknown trove of coral biodiversity and helped improve seafloor maps of the Labrador Sea, according to a new study published in Ecology and Society. “The benefits of working together are really illustrated in this project,” Cote said.

Clues from the Deep

Cold-water corals are sensitive creatures, slow to recover from damage by deep-sea trawlers, oil and gas exploration, and climate change stressors such as rising water temperatures. They are also a priority for conservation because they provide vital habitats for many species. But to protect coral ecosystems in Labrador, the researchers first needed to find them.

Researchers knew from past studies that many coral species thrive on underwater rocky slopes rather than in mud. But they had one big problem: The seafloor maps for the Labrador Sea are notoriously inaccurate, meaning they couldn’t be used to identify patches of steep seafloor to start the search.

“What helped is that local people pinpointed where things were. They identified the haystack to look in instead of having a barn full of hay and looking for the needle.”

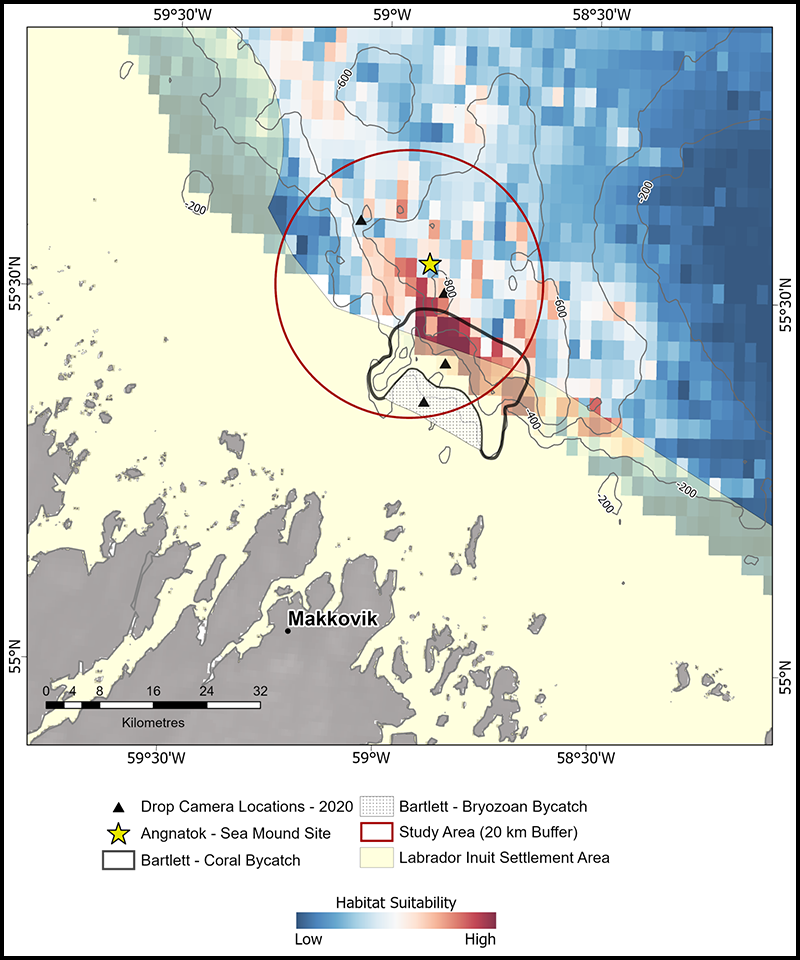

The rise on the seafloor that Angnatok found was a clue for where coral might be, because seamounts often slope off steeply on all sides. A different local fisher, Capt. Bartlett, had discovered coral in his fishing nets a few kilometers away from Angnatok’s seamount.

“What helped is that local people pinpointed where things were,” said Vincent Lecours, a geographer at Université du Québec à Chicoutimi who wasn’t involved in the study. “They identified the haystack to look in instead of having a barn full of hay and looking for the needle.”

Computer models that predict the locations of coral habitats using fishing and environmental data also pointed to locations close to Bartlett’s and Angnatok’s points of interest. Using these data, the team triangulated an area to search for coral.

Improving Seafloor Maps to Refine the Hunt

“That’s when these beautiful corals appeared on the control room screen.”

Aboard CCGS Amundsen in 2020 and 2021, the researchers surveyed the target region with a multibeam sonar to improve the existing seafloor maps.

Within the maps, they could pick out an area of sloping bedrock—a good candidate for coral growth. To get a better view, the researchers piloted a remotely operated vehicle into the depths and faced the cliffs. “That’s when these beautiful corals appeared on the control room screen,” Cote said. “Everybody was pretty excited.”

From the video, they could see a whole host of species of coral anchored to the cliffs, with the types of species changing at different depths. They had discovered an area of high biodiversity in the black box that is the Labrador Sea. They named the area the Makkovik Hanging Gardens.

In addition to identifying biodiversity hot spots for conservation, discoveries like this one can also help local fishers avoid areas of the ocean that can potentially damage fishing gear. “I try to share information with other fishermen and say, ‘If you want to keep your nets fishable, avoid this spot,’” Angnatok said.

By improving the maps of this part of the Labrador Sea, the researchers have also identified new cliffs to explore. “It’s an area that we probably wouldn’t have surveyed for a long time had we not learned from this particular exercise,” Cote said. They already think they’re on to something. Angnatok and several other researchers dropped a camera into the water off his boat. “We just got a glimpse of it,” Cote said, “but we caught another coral garden that we’re hoping to explore soon.”

—Andrew Chapman (@andrew7chapman), Science Writer

This news article is included in our ENGAGE resource for educators seeking science news for their classroom lessons. Browse all ENGAGE articles, and share with your fellow educators how you integrated the article into an activity in the comments section below.