Accurate forecasting of volcanic eruptions is life-saving science: Millions of people worldwide live in the shadow of a volcano.

Researchers have now analyzed precise records of tens of thousands of earthquakes in Iceland and produced one of the most detailed pictures of how seismicity traces the movement of magma deep underground. These kinds of measurements, which reveal the location of molten rock, can be used to better predict when and where eruptions will occur, the scientists suggest.

Lucky Placement

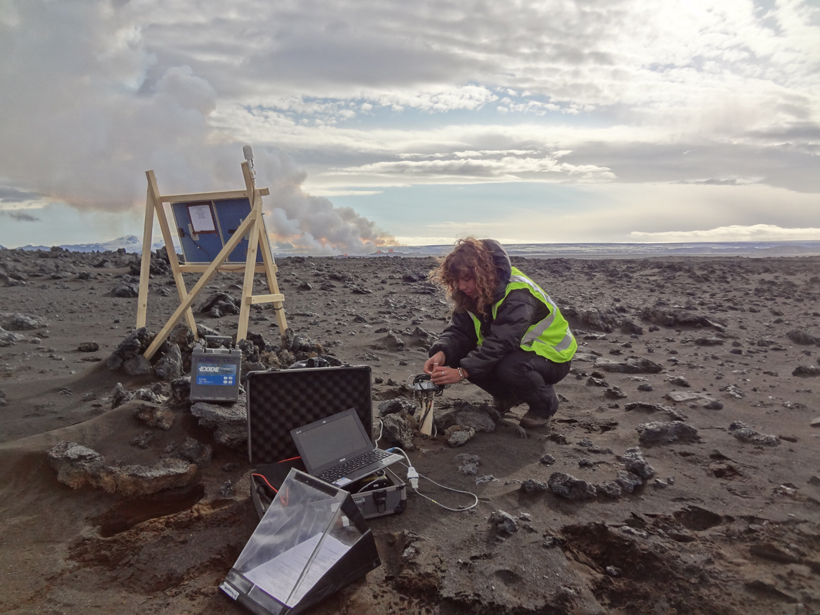

Robert White, a geophysicist at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, admits he was lucky. He and his colleagues on the Cambridge Volcano Seismology team had already installed over 60 seismometers near Iceland’s Bárðarbunga volcanic system when magma began moving underground in 2014.

The instrumentation was intended for a neighboring volcano, but White and his collaborators soon realized the seismometers were perfectly placed to capture the rumblings of Bárðarbunga. “They were in just the right place,” said White. (The researchers also rushed to place 10 additional seismometers.)

Bárðarbunga would go on to belch 1.6 cubic kilometers of molten rock, dwarfing the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull. The first eruption occurred for a few hours on 29 August, and the next one came on 31 August, this time lasting 6 months.

Earthquakes and volcanic eruptions often go hand in hand: The movement of molten rock underground—a magmatic intrusion—triggers ground shaking as it deforms the surrounding rock.

The Bárðarbunga magmatic intrusion cut a 48-kilometer-long path through Earth’s crust over the course of 2 weeks. And earthquakes were plentiful: White and his colleagues recorded over 30,000 ranging in magnitude from 0.5 to 3.5.

Precise Triangulation

White and his colleagues pinpointed the locations of the earthquakes in three-dimensional space by triangulation. By very precisely measuring—to within 0.001 second—how long it took the earthquake waves to travel to different seismometers, the researchers estimated locations with uncertainties of only about 100 meters. That’s about 10 times better than most other studies, said Jenny Woods, a volcano seismologist at the University of Cambridge and member of the research team.

“Monitoring microseismicity is one of the most important tools we have for tracking intrusions of magma in real time.”

Using the locations of the recorded earthquakes, the researchers inferred that Bárðarbunga’s magma moved in fits and starts—sometimes it stalled, and sometimes it moved forward at nearly 5 kilometers per hour (roughly human walking speed).

These kinds of measurements make it possible to track the path of magma underground, said Woods. “Monitoring microseismicity is one of the most important tools we have for tracking intrusions of magma in real time.”

Their results were published earlier this year in Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

This study highlights the importance of having a dense monitoring network, said Luigi Passarelli, a volcanologist at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia not involved in the research. “[It] can lead to better understanding of physical processes and eventually to improved real-time risk mitigation.”

White and his colleagues will be returning to Iceland this July to download data from the 27 seismometers still deployed around Bárðarbunga. Collecting these measurements is crucial because the volcano appears to be refilling with magma underground, said White. “It’s still active.”

—Katherine Kornei (@katherinekornei), Freelance Science Journalist

Citation:

Kornei, K. (2019), More than 30,000 earthquakes trace the movement of magma, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO123459. Published on 14 May 2019.

Text © 2019. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.