Groundwater comprises a third of all freshwater on Earth and provides humans with a necessary source for irrigation and drinking water. However, until recently, the only groundwater supply estimates relied on rough calculations dating back to the mid-1970s. A new study provides the first data-driven calculations of the total supply and uncovers how much usable groundwater we have left.

If the total volume of groundwater in the top 2 kilometers of crust were extracted and pooled across the continents, it would be about 180 meters deep.

To perform their calculations, researchers drew from a wealth of existing geochemical, geologic, and hydrologic data. “In the past, all of this data was kind of hidden in books and maps, and now it’s much more readily available for these kinds of novel science questions,” said Tom Gleeson, a hydrogeologist at the University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, and the lead researcher of the study, which was published Monday in Nature Geoscience.

The study revealed that if the total volume of groundwater in the top 2 kilometers of crust were extracted and pooled across the continents, it would be about 180 meters deep. But the quantity of what the researchers call “young” groundwater is far smaller.

Young Groundwater

Gleeson defines young groundwater as groundwater that has been recharged within the last 100 years. Although some regions—for instance, California—can use older groundwater, it is far too brackish in most places. So communities generally rely on young groundwater sources, he said. “If you take all that young groundwater out of the Earth, it would only be 3 meters high. So about the height of a stop sign,” Gleeson said.

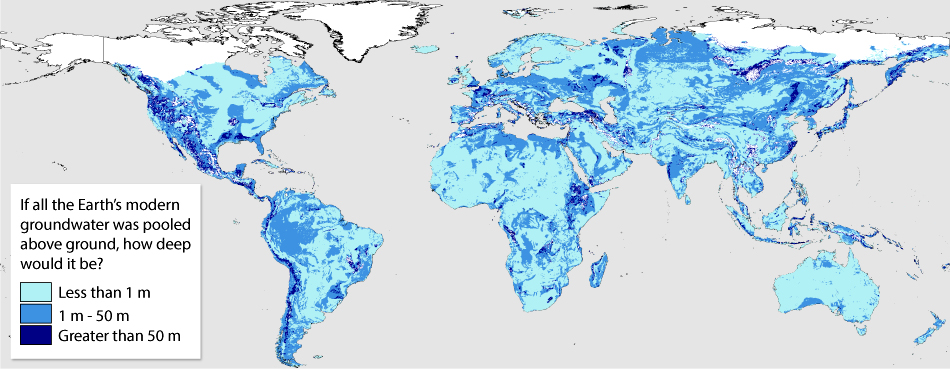

Of that young groundwater, he and his team have further focused on groundwater that accumulated in roughly the past 50 years, which they called “modern” groundwater. This analysis showed that very little—only 6%—of total groundwater gets replenished in roughly a human lifetime. “We’re using our groundwater resources too fast—faster than they’re being renewed,” Gleeson said in a press release.

The researchers identified the modern groundwater by how much tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, the water contains. Modern groundwater contains higher concentrations of tritium than older groundwater because tritium fallout from thermonuclear tests in the mid-20th century spiked the water. Gleeson and his colleagues developed a database of tritium measurements, which they used with watershed models to estimate the volume of the modern groundwater.

The new study provides the first estimate of the volumes of young and modern groundwater and a map of the distribution of modern groundwater across the globe, Gleeson said. The team’s estimate for total global groundwater closely matched the total groundwater calculations from the 1970s, he added.

Going Deep

“The depth of the groundwater is really important to know in terms of how deep we need to drill and how costly that would be.”

Gleeson said he hopes the team’s new findings will enable policy makers to make more informed decisions about groundwater use in the future. “The depth of the groundwater is really important to know in terms of how deep we need to drill and how costly that would be,” he said. The new maps might also prove useful for locating regions where industry and agriculture are putting usable groundwater at risk.

The team plans next to map the amount of time it will take before groundwater extraction around the world begins to affect the flow of the life-supporting rivers fed by groundwater, Gleeson said.

—Shannon Kelleher, Writer Intern

Citation: Kelleher, S. (2015), New study reveals how much groundwater remains, Eos, 96, doi:10.1029/2015EO040089. Published on 20 November 2015.

Text © 2015. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.