Namaqualand, an arid region along the southwestern coast of Africa, sits at the confluence of two prevailing winds: westerlies from the Atlantic Ocean and easterlies from the Indian Ocean. That makes it tricky to model the region’s response to climate change.

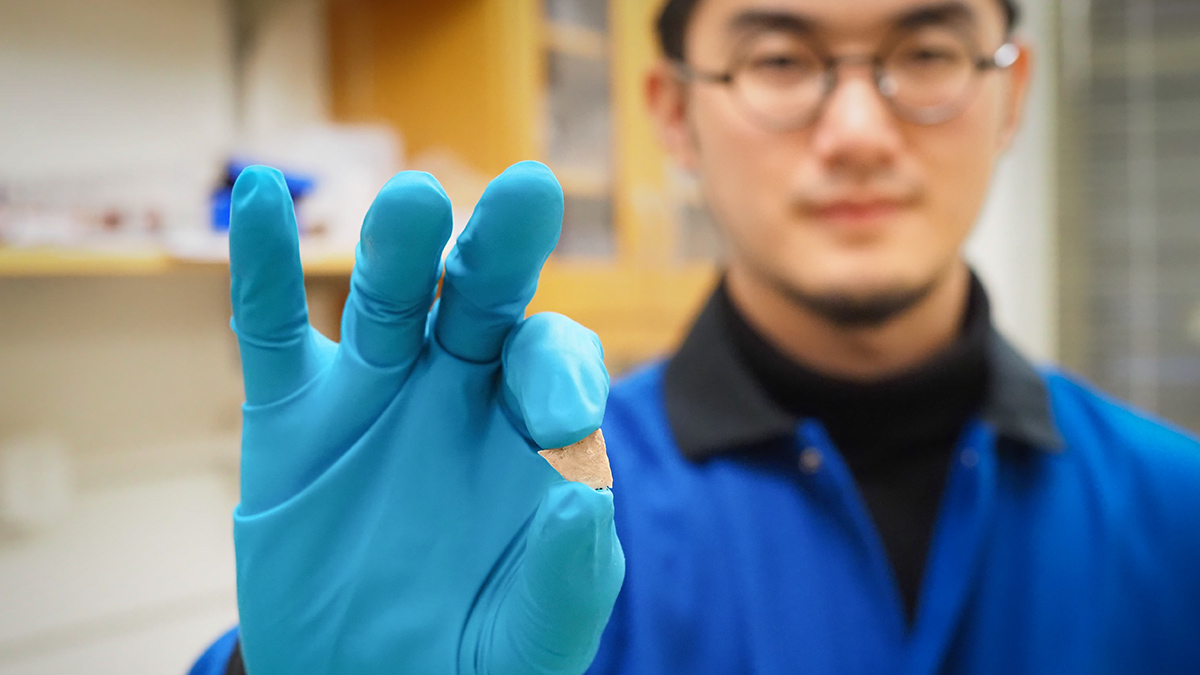

Scientists can turn to its past climate to anchor models. And a new study looks to a unique source of data: ostrich eggshells. Geochronologists analyzed fragments of ancient eggshells collected at an archaeological site in Namaqualand. Their nitrogen isotope analysis verified that the region was wetter leading up to the end of the last glacial period 11,700 years ago.

“Global warming is going to reshape and redistribute precipitation around the world,” said lead researcher Mingzhe “Damon” Dai, a geoscience graduate student at Princeton University in New Jersey. Data such as these can inform changes in hydrology that we might soon experience, he explained.

From Rain to Eggshells to the Lab

“Observations on the paleoclimate and paleoenvironment of southern Africa…are in short supply.”

“Observations on the paleoclimate and paleoenvironment of southern Africa…are in short supply,” said Warren Sharp, a geochronologist at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved with this research. Ostrich eggshells, which are regular archaeological finds in the region, “are archives for such information,” he said.

Damon and his team partnered with archaeologists studying Spitzkloof A, an ancient human settlement site in northern Namaqualand that dates to the middle Stone Age.

The archaeologists supplied the team with dozens of small ostrich eggshell fragments collected at the site that were carbon dated at 17,000–51,000 years old. People of the time used the shells as containers and an art and language medium and to create social networks.

Drier conditions remove nitrogen (N) from soil, preferentially eliminating the lighter isotope, 14N, over the heavier isotope, 15N. Studies have found that a soil’s 14N to 15N ratio (known as δ15N) is recorded by growing plants, which are eaten by creatures. That ratio is then incorporated into any animal by-products, including eggshells.

Ostrich eggshells therefore store a record of rainfall at the time they were made. Measuring δ15N in several eggshell fragments of different ages can create a timeline of Namaqualand’s past precipitation, Damon said.

For each of the 79 samples, the team cleaned, crushed, and dissolved the eggshells, then extracted the organics in the shell fragments, oxidized the sample into nitrates, and converted the nitrates into nitrous oxide (N2O). They then measured the ratio of N2O made with 14N versus 15N with a mass spectrometer to calculate δ15N.

From these values, the researchers calculated that the mean annual precipitation while the eggs were forming was about 175 millimeters per year, averaged across the sample period. That’s 1.6–3.5 times higher than it is today.

Though there was a lot of variation in the rainfall amounts calculated from the shells, the youngest samples suggested that precipitation increased near the end of the last glacial period and leading up to earliest deglaciation, with possibly up to 300 millimeters of rainfall per year.

This research, which has not yet been peer reviewed, will be presented today at AGU’s Annual Meeting 2023 in San Francisco.

Small Shell Shards

Brian Chase, a paleoclimatologist at Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and Université de Montpellier in France, said that this research seems in-line with existing rock records suggesting that Namaqualand was slightly wetter at the end of the Pleistocene (2.58 million to 11,700 years ago) than it is today.

Chase, who was not involved with the research, cautioned that because each eggshell records such a short period of time, we can expect a lot of variability in calculated rainfall amounts. That noise can highlight how stable (or not) the climate was over that period, he said, but “it means that large data sets are required to construct coherent, reliable time series.”

Sharp agreed. “Each eggshell records the diet of only a single ostrich for a short period,” he said. Ten to 20 samples from the same time would be needed to average out year-to-year variations and an individual’s foraging habits, he explained.

Damon said his team has a possible way to overcome that noise. Previous analyses of nitrogen isotope ratios required large shell fragments—which are hard to find—because the analyses tracked the isotope fractions within molecular nitrogen (N2). That gas is also the primary constituent in Earth’s atmosphere, so N2 contamination from modern air adds more noise to each sample, Damon said. “We need larger samples to produce enough N2 to get a measurement.”

“But now we are measuring the N2O. We don’t have so much N2O in the air,” so very small quantities of eggshell can produce detectable signals, Damon continued. The team needed only 3–5 milligrams of eggshell for each measurement, rather than the 300 milligrams that would have been needed had they looked at N2. Archaeological sites are more likely to have small shell fragments, so it’s easier to collect enough samples to create a precipitation time series.

This technique could potentially be applied at other archaeological sites where large shell pieces are rare but small shards are abundant. Damon said the team is looking to analyze more samples from Spitzkloof A and older archaeological sites in Namaqualand to improve the accuracy of their analysis and fill in more of the region’s precipitation timeline.

—Kimberly M. S. Cartier (@AstroKimCartier), Staff Writer