In 1991, the U.S. General Services Administration unearthed a staggering archaeological find during construction of a federal office building in lower Manhattan. While digging the building’s foundations, construction crews stumbled upon skeletal remains from the “Negroes Buriel Ground,” the largest and oldest burial site of free and enslaved Africans in what is now the United States.

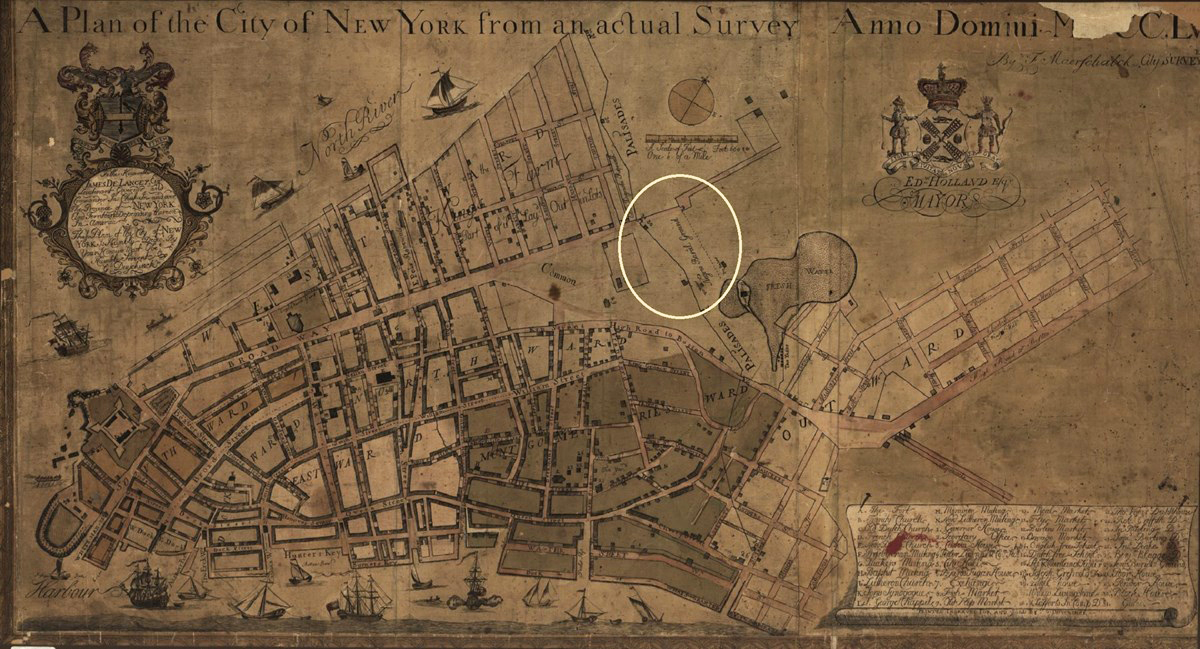

Historians knew the burial ground to be a 2.7-hectare (6.6-acre) cemetery of more than 15,000 Africans and their descendants who lived in New York during the 17th and 18th centuries. Africans were not allowed to bury their dead in church cemeteries in colonial New York, so colonists gave them a swath of undesirable land outside the original city walls in which to bury their dead.

The burial ground was filled in and covered over in the early 19th century, and it lay mostly forgotten under 9 meters (30 feet) of earth until the construction of that office tower in 1991.

Anthropological Research

Rediscovery of the burial ground changed anthropologists’ understanding of slavery in New York City, according to Michael Blakey, an anthropologist at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Va., and formerly of Howard University in Washington, D.C.

Skeletal remains and burial artifacts of more than 400 individuals were exhumed upon discovery of the site, which was renamed the New York African Burial Ground. Thanks to a concerted effort by then New York City mayor David Dinkins and the local African American community, in 1993 the excavated remains were brought to Howard University, the country’s leading African American research university.

Blakey, then director of Howard’s W. Montague Cobb Research Laboratory, led efforts to analyze the skeletal remains and reconstruct the lives of the individuals interred in the cemetery.

The remains and burial artifacts provided remarkable insight into the lives of Africans in colonial New York.

The remains and burial artifacts provided remarkable insight into the lives of Africans in colonial New York. Bones and teeth showed evidence that the enslaved Africans often performed hard manual labor, suffered from malnutrition, and had short life spans. Artifacts showed anthropologists evidence of the African cultures and tribes from which the individuals came. The burial ground site was designated as a national historic monument in 1993, and the remains were ceremoniously reburied in 2003.

Although the remains were reburied, samples of grave soil from the burial ground remained at the Cobb Research Lab. In 2015, Carter Clinton, then a graduate student at Howard, began analyzing the soil samples to see if they could tell him more about the lives and deaths of the individuals interred in the burial ground.

Carter’s work, some of which was recently published in Scientific Reports, sheds more light on the diet of enslaved Africans in New York and some of the infectious diseases they suffered from.

In this podcast episode, Carter recounts the history of the New York African Burial Ground and describes what he has learned about the lives of Africans in colonial New York from the grave soil samples. Carter discusses how his work helps shape the narrative of slavery in New York and how it fills in a piece of American history long forgotten.

—Lauren Lipuma (@Tenacious_She), Public Information Program Manager, AGU

Citation:

Lipuma, L. (2020), Podcast: Exhuming a buried piece of American history, Eos, 101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO140349. Published on 18 February 2020.

Text © 2020. AGU. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.