Microplastics seem to be everywhere these days. From remote mountaintop glaciers to human guts, tiny pieces of plastic appear in the most unexpected places.

In aquatic environments, microplastics have been a known pollutant since the 1970s, when several studies found large quantities of synthetic fibers and plastic fragments in the North Atlantic Ocean. However, little is known about how and where these particles originate. For a long time, researchers thought they were fragments from larger plastic objects that broke off at sea, but recent studies show that reality might be more complex.

The researchers looked for microplastics in surface waters, along sandy beaches near the delta, and in the sediments at the bottom of the estuary.

A group of researchers from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in Spain has measured the concentration of microplastics in the delta of the Ebro River, one of the largest rivers on the Iberian Peninsula. The researchers looked for microplastics in surface waters, along sandy beaches near the delta, and in the sediments at the bottom of the estuary.

Their findings confirm what other researchers have been suspecting for a while: Rivers are highways that microplastics generated inland follow to the ocean.

At a rate of 3.5 particles per cubic meter of water, the Ebro River dumps 2.2 billion pieces of microplastic into the Mediterranean Sea every year. This number is actually in the medium-low range of what’s been found in other rivers in Europe and elsewhere. In extreme cases of heavily polluted rivers near densely populated areas, such as the Pearl River delta near Guangzhou in China, researchers recently reported concentrations ranging from 379 to 7,924 pieces per cubic meter of surface water. In the Seine River near Paris, another study reported 3 to 108 particles per cubic meter in 2015.

The new study is one of the few that paints a global picture of microplastic distribution in river estuaries, which are key transition zones where fresh water and seawater meet.

“Most studies report concentration in surface water, or sediments, or in the seafront of the river, but it’s really hard to make a global diagnostic of the situation with that approach,” says Laura Simon-Sánchez, a researcher and doctoral student at the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and first author of the study.

Simon-Sánchez and her colleagues found that microplastics tend to accumulate in sediments at the bottom of the delta, where in the Ebro they found a mean concentration of 2,052 particles per kilogram of sediment. Prevailing currents can also transport many particles that wash ashore on beaches north of the delta. On these beaches, the team found around 400 particles per kilogram of sand. Their work was published in July in Science of the Total Environment.

“What researchers have finally realized is that all that plastic pollution is mainly coming from land-based sources, so, of course, it makes sense to look at rivers first.”

“We’ve seen that bottom sediments are clearly where most plastics accumulate, but we think that storms can remobilize them and push them out to sea,” says Simon-Sánchez. “Our next goal is to try to understand for how long these plastic particles stay in each environmental matrix.”

Where Do Microplastics Come From?

Today, there aren’t many studies that can shed light on how microplastics get into rivers.

“The problem is that everybody is so concerned about microplastics and plastic pollution in marine systems that we have very little knowledge about microplastic contamination in freshwater systems,” says Martin Wagner, an environmental toxicologist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. Wagner was not involved in the Ebro River study. “What researchers have finally realized is that all that plastic pollution is mainly coming from land-based sources, so, of course, it makes sense to look at rivers first.”

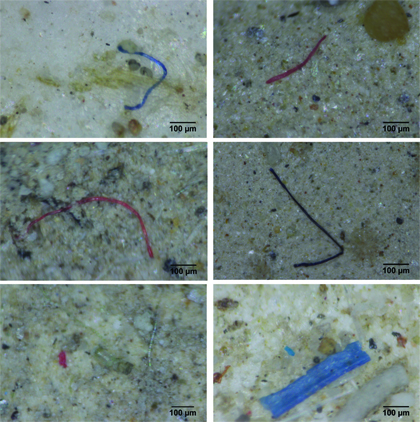

Overall, 70% of the microplastics found in the Ebro River delta are synthetic fibers, followed by plastic fragments and films. Simon-Sánchez thinks that these fibers probably come from domestic and commercial laundry that wastewater treatment plants fail to remove. However, Wagner disagrees and points out that there are many diffuse sources and probably even more fibers reach the rivers through their surface than from wastewater.

According to Wagner, it will be very hard to reduce the amount of synthetic fibers in the rivers unless more studies look into how they get there in the first place. This is one of the main challenges with microplastics because they have many diffuse sources, he says.

Even without knowing how these particles get into rivers, it’s becoming clear that rivers are not only the first transport road for plastic pollution to the ocean but also an important sink for plastic pollution.

The processes of accumulation and degradation of microplastics in river sediments are still poorly understood, and little is known about how they affect aquatic life and maybe human health.

“It might still be early to ring a big alarm bell,” Wagner says. However, he adds that in a business-as-usual scenario, “we will see a risk to aquatic environments very soon.”

—Javier Barbuzano (@javibarbuzano), Freelance Science Journalist

Citation:

Barbuzano, J. (2019), Rivers are a highway for microplastics into the ocean , Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO130375. Published on 09 August 2019.

Text © 2019. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.