Tumbling boulders have etched trails on the lunar surface and left a record of recent seismic activity at Mare Orientale, a large lunar basin straddling the nearside and farside of the Moon.

The trails were spotted by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC), a system of cameras orbiting the Moon and capturing detailed images of its surface. Researchers led by P. Senthil Kumar of the National Geophysical Research Institute (NGRI) in Hyderabad, India, previously analyzed such images to characterize seismic activity at Schrödinger and Laue craters. Last month, in work presented at AGU’s Fall Meeting 2019 in San Francisco, the research group reported on recent activity at Mare Orientale.

Information about where moonquakes occur and how often they rattle the lunar landscape will be crucial for NASA’s Artemis program.

“Recently means around 35,000 years ago,” said Rupali Mohanty, a planetary scientist at NGRI, “which is very recent for the Moon.”

Additional information about where moonquakes occur and how often they rattle the lunar landscape will be crucial for NASA’s Artemis program, which plans to land humans on the Moon by 2024.

Moonquakes: Past

Seismometers placed during the Apollo missions—starting with Apollo 11—provided the first evidence of seismic activity and detected multiple types of moonquakes. Shallow moonquakes occur between 20 and 30 kilometers below the lunar surface and are relatively rare: The Apollo era instruments captured only five per year. But these rare occurrences were also the strongest examples of seismic activity on the Moon. For example, the 1975 moonquake at Laue crater registered a magnitude of 4.1.

Researchers are actively exploring what causes shallow moonquakes. A study published in May 2019 suggested that they occur as the Moon’s interior cools and shrinks, leaving lunar surfaces wrinkled up like a raisin. However, the Apollo seismometers also detected moonquakes where there aren’t telltale ridges, indicating that further research is required.

Moonquakes: Present

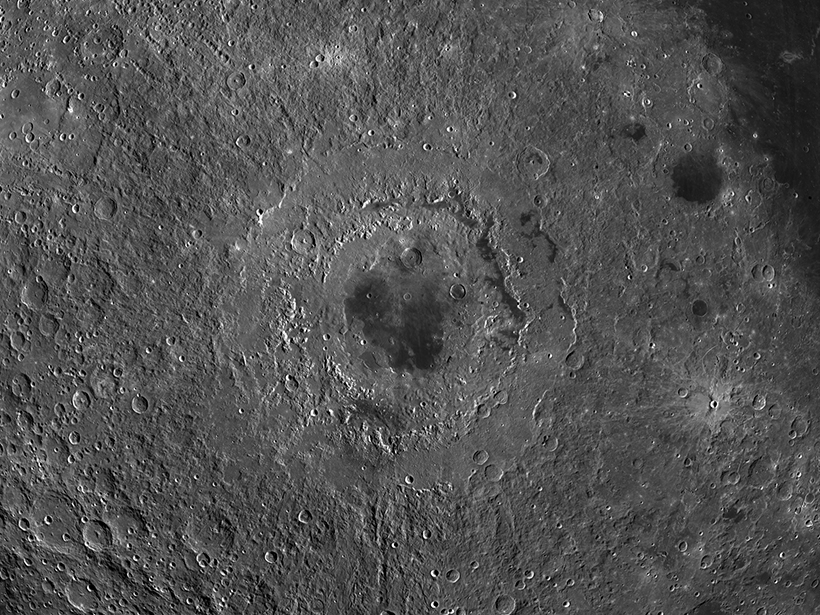

In the current study, Mohanty and colleagues visually inspected the lunar surface at Mare Orientale, a lunar basin measuring 950 kilometers in diameter. The researchers analyzed LROC images and counted over 6,000 boulder falls at 141 sites.

They observed a variety of boulder trail patterns imprinted on the lunar surface, including sliding, rolling, and bouncing. Trails were perfectly preserved because the Moon lacks an atmosphere. The slope of the examined areas was less than 30°, meaning that the areas weren’t steep enough for boulders to just roll down by themselves, Mohanty said. Some kind of seismic activity had to kick-start these boulders into motion.

Mohanty and her colleagues were also able to estimate when the boulders tumbled by checking which came first: the trail or the crater. If the trail overlapped an impact crater, which could be dated using conventional crater counting techniques, the boulder started rolling after the crater formed. The researchers found trails superimposed on craters formed 35,000 years ago, indicating that seismic activity occurred recently. They also found trails where there weren’t any impact craters—these trails must have occurred even more recently, potentially as a result of a magnitude 2.7 moonquake that was detected in the region in 1972.

“I really like the way the group has done this detailed mapping of all the different boulders and shown where they fall from,” said Ceri Nunn, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., who was not involved in the study. “They even seemed to suggest, I think very convincingly, that there were different events, possibly millions of years apart.”

Moonquakes: Future

The goal is to develop a moonquake “signature” based on boulder trail measurements.

Mohanty’s goal is to develop a moonquake “signature” based on boulder trail measurements, including the size of the boulders that moved, the distance they traveled, and the slope of the underlying terrain. Such signatures could help identify new moonquake epicenters.

However, more data may be needed before researchers are able to make such predictions. “If you had new seismic data and cameras going over the surface, then yes, I think that’s a possibility,” Nunn said.

The Indian Space Research Organization planned to place additional seismometers on the Moon as part of its Chandrayaan-2 mission, which launched in July 2019. Unfortunately, the Vikram Lander experienced a “hard landing” and wasn’t able to safely deliver instruments to the lunar surface. Mohanty is hopeful that Mare Orientale may still be a place to study moonquakes, perhaps even with the upcoming Chandrayaan-3 mission planned for 2020.

—Jack Lee ([email protected]; @jackjlee), Science Communication Program Graduate Student, University of California, Santa Cruz

Citation:

Lee, J. (2020), Rolling rocks reveal recent moonquakes, Eos, 101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO138383. Published on 08 January 2020.

Text © 2020. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.