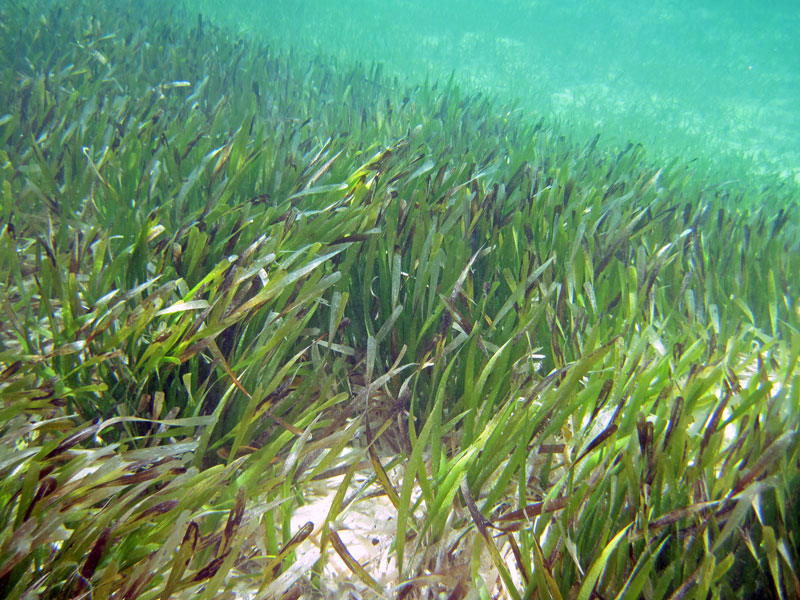

The Bahamas is friendly to tourists and seagrass for the same reasons: Its islands enjoy a warm climate and clear ocean waters.

The Atlantic waters off the coast of the Bahamas are home to up to 41% of known seagrass meadows in the world, and new research published in Communications Earth and Environment shows that these meadows accumulate roughly 2–3 billion kilograms of carbon annually. Though that’s less carbon than sequestered by mangrove stands (22–24 billion kilograms) or salt marshes (13 billion kilograms) globally, for seagrass in the Bahamas alone, it’s a significant reserve.

But it’s not as much as researchers expected to find.

Until recently, scientists hadn’t measured how much seagrass surrounds the Bahamas, much less its carbon storage capacity.

Carbon is stored in the plants as they grow and is released to seafloor sediment through their roots or debris. Locking away carbon in this detritus prevents it from being released into the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas, at least for a time.

In the new study, a team of scientists measured the amount of organic carbon stored in sediment beneath 10 Bahamian seagrass meadows. Divers gathered sediment cores of different lengths, and scientists dried each core’s contents. They then removed inorganic material to determine the density of organic carbon in the sediment.

Using carbon-to-nitrogen ratios as well as carbon isotopes as tracers, the researchers calculated how much organic carbon came from each source in the sediment, including macroalgae, cyanobacteria, phytoplankton, and seagrass. Longer sediment cores, up to 56 centimeters (26 inches) long, were analyzed for lead isotopes, which helped researchers pinpoint sediment age and extrapolate how quickly sediment accumulated over time.

Seagrass contributed roughly a quarter of the total organic carbon stored in the sediment, but the other sources were also significant. This finding “really struck me,” said Dan Friess, a coastal scientist at Tulane University who was not part of the new research, pointing to a need for conservation efforts that go beyond seagrass alone.

Although the carbon storage potential in seagrass is startling, Friess was quick to put it in perspective. “The scale of climate change challenges is huge,” he said. “Seagrasses alone are not going to solve it.”

The data also showed that denser meadows stored more carbon than sparse ones and that meadows with both Thalassia testudinum (turtle grass) and Syringodium filiforme (manatee grass) locked away more carbon than single-species meadows.

Diving Deep

Researchers estimate the meadows cover 67,000 to 93,000 square kilometers (26,000 to 36,000 square miles) of seafloor, making them the largest in the world.

But this “substantial global blue carbon hotspot” is not as carbon rich as scientists predicted. “The seagrass is quite dense,” said coauthor and marine ecologist Chuancheng Fu from King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia. “So I expected the carbon content to be higher.”

Fu traces this lower-than-expected carbon content to several factors.

“This emphasizes the importance of conserving the seagrass to [mitigate] more carbon emissions.”

First, clay particles, which efficiently cling to carbon, are less common in the Bahamas than in marine sediment elsewhere, such as the east coast of Africa or Scotland. The lower clay content contributes to seafloor sediment in the region being relatively coarse, which makes it harder for organic carbon to become trapped in the sediment and linger in the ecosystem.

Phosphorus in Bahamian seafloor sediment is also relatively scarce. Without this nutrient, seagrass grows more slowly, and there is less plant matter to decompose and settle on the ocean floor.

Finally, carbon storage in Bahamian seagrass meadows may also be limited “due to human activities that disturb the seagrass, which can lead to a reduction of the carbon stock,” Fu said. The researchers saw a decrease in organic carbon coming from seagrass starting in the 1980s and noted that the decline is likely due to growth in boating traffic and tourism.

“This emphasizes the importance of conserving the seagrass to [mitigate] more carbon emissions,” Fu said. Honing estimates of seagrass’s carbon storage potential, he said, may bolster such conservation efforts.

—Robin Donovan (@RobinKD), Science Writer