Bobbing in the waters off New York City is an unusual sight: a double-hulled Polynesian voyaging canoe, its red sails furled. The Hōkūle‘a is on a mission to sail around the world, navigating by the methods that ancient sailors used. Stars, the Sun, and ocean swells serve as the navigator’s tools when land vanishes over the horizon.

As scientists look at how traditional sailors learned to sail, they’re finding that humans can be remarkably good at learning to feel swells and navigate by them. In fact, ancient navigators may have relied on wave patterns that modern scientists are still working to model.

Navigating the Seas

The Hōkūle‘a began its journey in Hawaii in May of 2014. Although the 12-person crew of the Hōkūle‘a does carry a GPS for emergencies (and to broadcast their location to fans), the navigators are forbidden from looking at it. They don’t need to: In unfamiliar waters, the Sun and stars act as a compass. So the crew must learn the names and positions of hundreds of stars.

On a cloudy night, that aid vanishes. Instead, the navigator uses ocean swells, which travel in a consistent direction. If the crew already knows the direction they should be heading in relation to the ocean swells, the navigator can keep the boat on its previous path, even over great distances.

“The waves are pretty much the same the whole way, so you’re just maintaining the direction,” said Kālepa Baybayan, captain and navigator of the Hōkūle‘a.

A Swelling Mystery

The regularity of the swells may have helped ancient Polynesian voyagers, but to modern oceanographers, the waves pose a puzzle. These ocean swells are long-lived—they do dissipate over time as they travel across the sea, but “we still don’t know why the swells are dissipating,” according to Justin Stopa, a physical oceanographer at the French Research Institute for Exploration of the Sea (Ifremer).

The longevity of [ocean] swells may have helped ancient Polynesian voyagers, but to modern oceanographers, it still poses a puzzle.

Current theories hold that turbulent interaction between the air and waves may eventually slow the water down, said Stopa. But because the waves only gradually decay, oceanographers’ current tools aren’t precise enough to easily capture a single swell’s dissipation, according to Stopa.

Oceanographers usually use a combination of satellite images of waves as they travel across the ocean, altimeter data from those satellites, data from buoys in the waves’ path, and computer models of the waves’ behavior—but until better satellites are launched in the coming years, Stopa said, his colleagues will struggle to find the data that give a definitive answer.

Studying how swells travel and transfer energy is important: When swells interact with islands, winds, and each other over distances, some of them can become massive rogue waves that can damage ships and drown beachgoers. On the other hand, proposed ocean-based generators could rely on swells to generate electricity—and finding the right place to put them is an important early step.

An Ancient Advantage

Some researchers have theorized that humans on boats like the Hōkūle‘a may even be better able to detect some types of waves than modern scientific instruments. A team of scientists has been working with traditional navigators in the Marshall Islands to hunt down the di lep, a type of wave that the islanders say marks out a “highway” between islands.

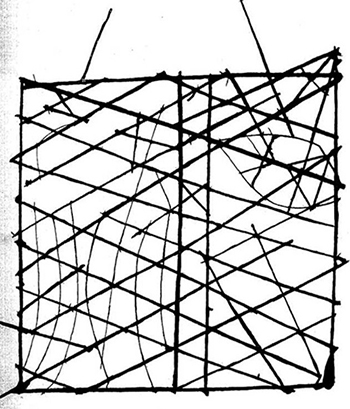

Navigators study wave maps made out of bent sticks and lie down blindfolded in canoes until they can sense the di lep. (Read an explanation of how such charts work here.) Marshallese navigators do seem to be able to make their way between islands in the chain with good accuracy, but the scientific team has thus far been unable to use buoys and models to definitively pin down the di lep.

[public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

The di lep, the team suspects, is caused by disruptions in long-lived swells as they are blocked by the islands and bounce off of them. “They’re very subtle,” said Joseph Genz, an anthropologist at the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo who worked with the Marshallese navigators.

The sailors on the Hōkūle‘a use similar techniques as they navigate near land, feeling the disruptions in the rocking of the boat to sense the shoreline, even when it’s out of sight. “There’s an observable change in the sea state as you approach islands,” said Baybayan. “The sea gets calmer as you get into the lee of the islands…and the quieting down of the ocean is a technique that you can use to identify the location of islands.”

Yachters and boaters of other cultures are also picking up these traditional navigational methods, according to Genz. In an emergency, being able to steer toward land without the aid of a GPS could save sailors’ lives, he said.

Cultural Pride

For the voyagers on the Hōkūle‘a and in the Marshall Islands, being able to navigate by environmental cues is also a matter of cultural pride. These groups are reviving practices that went extinct centuries ago in the case of the Hawaiian Islands and just over 60 years ago in the Marshall Islands, when nearby atomic testing irradiated and then exiled whole communities from their island homes.

“This revival is all about relearning how to navigate, but it’s also about this community regaining a sense of who they are,” said Genz.

After the Hōkūle‘a leaves New York City, its crew will travel up to the St. Lawrence Seaway before making their way back down the East Coast, stopping to share their navigational knowledge along the way. The crew plans to travel through the Panama Canal to the Pacific before winter hits. After that, they’ll be sailing home for Hawaii by way of Rapa Nui and Tahiti.

—Elizabeth Deatrick, Writer Intern; email: [email protected]

Citation:

Deatrick, E. (2016), Stars and swells guide a Polynesian canoe around the world, Eos, 97, https://doi.org/10.1029/2016EO054521. Published on 22 June 2016.

Text © 2016. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.