Rolf Hut owns the world’s only pair of temperature-sensing fisherman’s waders. Although, at the moment, they’re a tad primitive, held together with only epoxy and duct tape, they can send accurate temperature readings to a smartphone when the person wearing them stands in water.

In a paper published late last month in Geoscience Instrumentation, Methods and Data Systems, Hut and his colleagues document how they built and tested the temperature-sensing waders.

Birth of the Waders

To measure the temperatures of creeks, streams, rivers, and other bodies of water, scientists usually have to take data manually or use expensive equipment and repeatedly return to the area to set up and manage sensors, said Hut, an engineer at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands who specializes in hydrological data. He is lead author on the paper.

Scientists and fishermen would log a constant stream of digital information and store it online as they walked up and down streams.

As they were talking about hydrological sensing one night, Hut and his colleagues came up with the idea to affix temperature-sensing equipment to a pair of fisherman’s waders, which look like wet suit overalls attached to Wellington boots. The group imagined that an ideal pair of commercially manufactured temperature-sensing waders would connect to a smartphone app that would tag the temperature data with GPS coordinates and upload it to a repository on the Internet. This way, scientists and fishermen would log a constant stream of digital information and store it online as they walked up and down streams. Simultaneously, they could share the information with their fishing friends or scientific colleagues, said Scott Tyler, a hydrologist who studies environmental fluid dynamics at the University of Nevada, Reno, and coauthor on the paper.

Months later, Hut cobbled together a pair of temperature-sensing waders in his hotel room at the 2015 European Geosciences Union General Assembly in Vienna. He soldered wires to the tiny temperature sensor and inserted it into a hole drilled into the left boot. The waders did well at the meeting in demonstrations during which Hut stood in tubs of water, so he and his team decided to submit the novel pants to a real test.

Testing the Waders

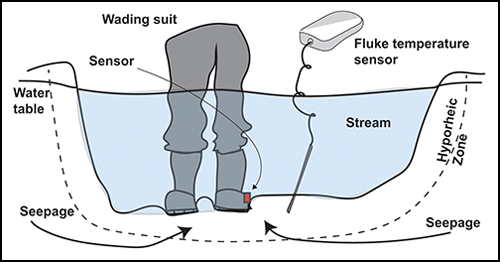

Usually, people wearing waders splash through “pristine alpine creeks,” Hut said. Not so lucky in the Netherlands, he noted, “what we have is 5-meters-below-sea-level ditches”—called polders—into which groundwater regularly seeps. On a sunny day in July 2015, adorned in the temperature-sensing waders, Hut sloshed through one of these muddy ditches, his boots sinking into the mud with every step. Wires soldered to the sensor ran up the side of the leg and attached to a small piece of electronic equipment in the chest pocket that Hut programmed to send temperature data to his phone. To compare, he also collected data with a handheld temperature-sensing probe.

In this test, the researchers wanted to find out if the waders could detect a quick change in temperature as well as a separate instrument does. In particular, Hut investigated if the waders could sense his stepping into the typically cooler area of a polder where cold groundwater seeps in. In fact, the boot sensor took longer to adjust than did the separate instrument.

Despite the waders’ less than perfect temperature sensitivity, Hut remains optimistic about their potential use in the field. “If every fisherman suddenly walked around with these, [the data] would be a highly valuable additional source of information” for scientists studying the dynamics of flowing bodies of water, he said.

The Future of Waders

Hut and his colleagues are currently in talks with a wader manufacturer to fabricate more-carefully assembled prototypes to share with scientists who would like to try out the temperature-sensing waders. The instrumented pants have sparked interest, particularly at the U.S. Forest Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the inventors said.

The waders could prove useful not only for studying temperature aspects of stream flows, Tyler said, but also for investigating how water temperatures affect populations of fish, like salmon and trout. As a potential area of study, the current drought in the western United States has decimated fish populations that depend on cool water to survive, Tyler noted.

“We could turn every fly fisherman into a mobile sensor.”

Waders could be used for citizen science, added Tyler, who likes to fish himself and knows how much time avid fishermen spend in waders. Hut agreed. “We could turn every fly fisherman into a mobile sensor,” he said.

—JoAnna Wendel, Staff Writer

Citation: Wendel, J. (2016), Temperature-sensing overalls offer scientific promise, Eos, 97, doi:10.1029/2016EO049119. Published on 28 March 2016.

Text © 2016. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.