More than 10,000 years ago, when the Sahara was still green, people living near the Nile migrated hundreds of kilometers from the river’s fertile banks.

During this African Humid Period, the frequency of heavy rainfall events rose fourfold, increasing flooding of the Nile. The flooding forced populations to migrate out to fossil rivers—smaller rivers shooting off from the Nile, less prone to such extreme water rises whose paths line southern Egypt and northern Sudan.

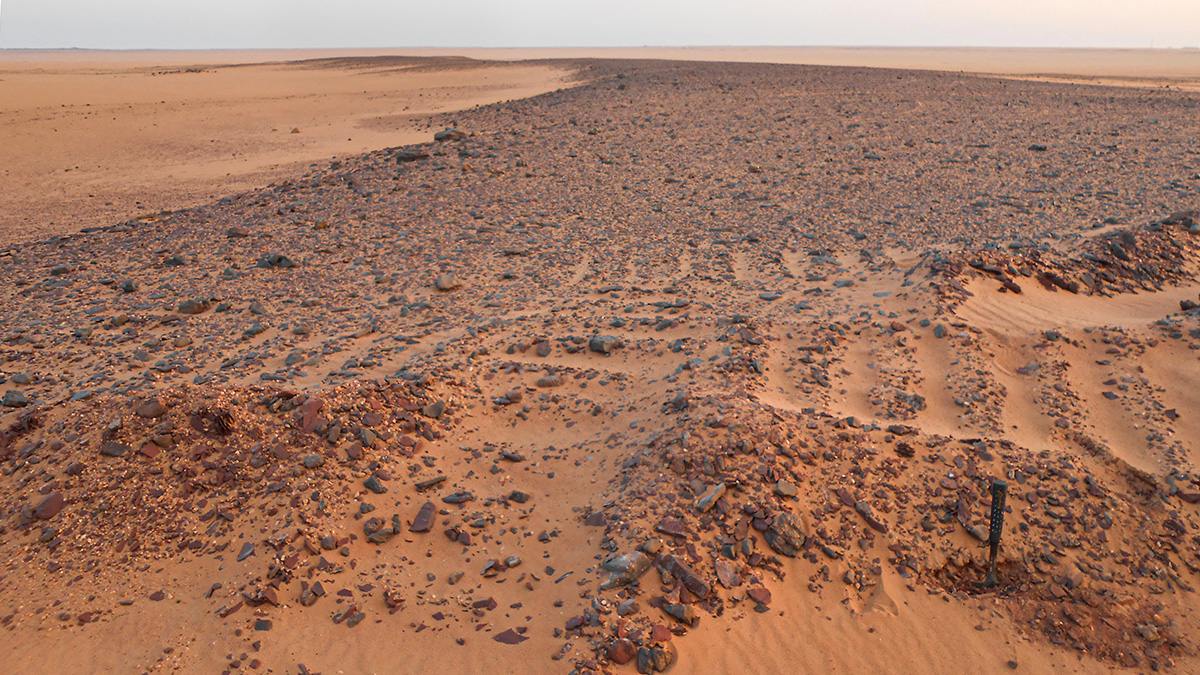

Recently, geologists led by researchers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) in Switzerland reconstructed the paleohydrology of six fossil rivers distributed across 38,000 square kilometers of the region. Satellite imagery was used to trace and map the rivers from source to sink, and this information was compared with known patterns of human migration in the region.

“We decided to conduct this research because the presence of Acheulean artifacts [hand axes] within one of those rivers suggested their sedimentary record would potentially yield interesting data about humid periods during the middle Pleistocene 800,000 years ago, an important climatic window with links to human expansion ‘out of Africa’ through the Nile corridor,” explained Abdallah Zaki, a Ph.D. researcher in the Department of Earth Sciences at UNIGE and lead author of the study.

Reconstructing Rivers

To reconstruct the paleohydrology of the entire region, researchers started small—by measuring pebbles.

Coarser clasts and “large pebbles indicate a high water discharge” because only high volumes of water could transport them, explained Sébastien Castelltort, an associate professor at UNIGE and a coauthor of the study.

Geologists also had to determine the surface area of the drainage basin, the area that connects water flowing upstream to the main stem of the river itself. “By combining these figures, we obtain the precipitation rate responsible for transporting the studied sediments,” Castelltort explained.

The age of the rivers was calculated using two different techniques. The first was carried out in collaboration with the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zürich using carbon-14 dating of organic matter from the fossil rivers. The second technique was optically stimulated luminescence, which measures the last time a quartz sediment was exposed to light. These calculations were made with specialists from the University of Lausanne.

Human Migrations

“The most significant surprise was to find that the ages of gravel deposits in these rivers clustered in the period of time corresponding to the so-called ‘African Humid Period,’” said Zaki. “We found that our paleohydraulic estimates indicated rainfall intensities in the range of 55–80 millimeters per hour—[that’s] 3–4 times more than before and after the African Humid Period.”

“The Nile was perhaps not a mere conduit for people fleeing Africa during the middle Pleistocene but also a source of the population that fled away into a greener Sahara during the African Humid Period.”

Such extreme conditions seemed to have forced people to abandon the Nile area for 3,000 years, said Zaki. The migration itself is well documented in analyses of archaeological occupation of the Nile Valley during the African Humid Period. The push and pull factors for this migration are debated.

The current “results suggest that the Nile was perhaps not a mere conduit for people fleeing Africa during the middle Pleistocene but also a source of the population that fled away into a greener Sahara during the African Humid Period,” Zaki said.

The results were published in Quaternary Science Reviews in November.

Documenting “Some Very Wild Rivers”

Reaction to the study has been mixed. “This is an important study because we knew that there were some very wild rivers in the Sahara during the African Humid Period, but we had until now no estimation of flow rate or rainfall intensity,” said Cecile Blanchet, a sedimentologist at the Helmholtz-Centre Potsdam–GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences not involved in the study.

“And these numbers tell us that the tributaries of the Nile that [Zaki and coauthors] studied were under similar rainfall regimes as what we know in the Mediterranean region, prone to generating flash floods. So one can well imagine that people might not deem the Nile banks a nice place to live if they experience flash floods on a regular basis while being surrounded by a lush Sahara,” Blanchet said.

If temperature and extreme rainfall events both increase (as forecasted by climate models in the last Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report), we can envisage that the Nile River and its drainage area might again turn into a hazardous place to live, she continued. Some hints of this change may have been given by the huge flooding in Sudan in 2020, she added.

Unprecedented Warming

Overall, the study is interesting, as it brings in additional information regarding the African Humid Period, said Francesco S. R. Pausata, director of the master’s program in atmospheric science at the University of Quebec in Montreal who was not involved in the research.

“It’s an important study, as it advances our understanding of past human response to climate change,” he said. Pausata was surprised, however, about the authors’ use of the Clausius-Clapeyron relation in explaining changes in precipitation at the regional scale. Although the Clausius-Clapeyron relation shows that the water-holding capacity of the atmosphere increases by about 7% for every 1°C rise in temperature and may be applied when considering global precipitation, he explained, it is not applicable to changes in rainfall at the regional scale that are, rather, driven by large-scale circulation changes. Therefore, Pausata said, the authors would have benefited from incorporating climate models instead of the Clausius-Clapeyron relation to explain rainfall changes.

Furthermore, “while this study tells a narrative of a multimillennial experiment in human ecodynamics, the sedimentary record cannot be used to infer anything about future climate. What we are experiencing does not have any precedents, and the warming is currently global, while in the African Humid Period it was confined to one hemisphere,” Pausata said.

Zaki said this study can be used to illustrate the tangibility of the impact of climate change on populations as it conveys the risks and challenges associated with global warming.

He does not anticipate similar internal migration from the Nile, however. “Actually, I wouldn’t expect a [modern] migration like what happened during the African Humid Period because the Sahara is currently hyperarid with no other water resources in the deep Sahara to sustain life.”

Instead, Zaki said, the findings ring true to Richard Pancost’s 2007 commentary in Nature Geoscience that the “past does not necessarily predict risks associated with climate change but it assures us that they are real.”

—Munyaradzi Makoni (@MunyaWaMakoni), Science Writer

This news article is included in our ENGAGE resource for educators seeking science news for their classroom lessons. Browse all ENGAGE articles, and share with your fellow educators how you integrated the article into an activity in the comments section below.