Toxic airborne emissions from volcanoes in Iceland may be dangerous even when pollution-monitoring instruments indicate that the air is safe, according to a new study. Volcanologists observing a 2014–2015 eruption in Iceland have found that even when air quality detectors had determined that sulfur dioxide (SO2) gas had fallen to acceptable levels in the air downwind from an eruption, another form of contamination known as sulfate aerosols had sneaked back, sullying the air.

The aerosols’ ingredients, tiny particles of sulfuric acid and trace metals, likely also harm people, but less is known about their toxicity than about the health consequences of SO2. Although Iceland’s public and environmental health agencies do not track sulfate aerosol concentrations, those pollutants contain “heavy metals found in human-made air pollution that are linked to negative health effects,” said Evgenia Ilyinskaya, a volcanologist at the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom, who led the study.

The findings by Ilyinskaya and her colleagues will appear in the August edition of Earth and Planetary Science Letters, which posted the results online in early June.

Record-Breaking Sulfur Dioxide Release

More than a cubic kilometer of lava gushed from the rift, along with record-breaking amounts of sulfur dioxide gas.

For 6 months spanning the end of 2014 and the beginning of 2015, an eruption from the Holuhraun fissure in the Bárðarbunga volcanic system of southeastern Iceland captivated the world. More than a cubic kilometer of lava gushed from the rift, along with record-breaking amounts of SO2, a common volcanic emission that can be extremely harmful to humans. The gas can damage the lungs, and it causes irritation of the nose and throat. Other scientists have estimated that the Holuhraun eruption emitted 1130 kilograms of SO2 every second.

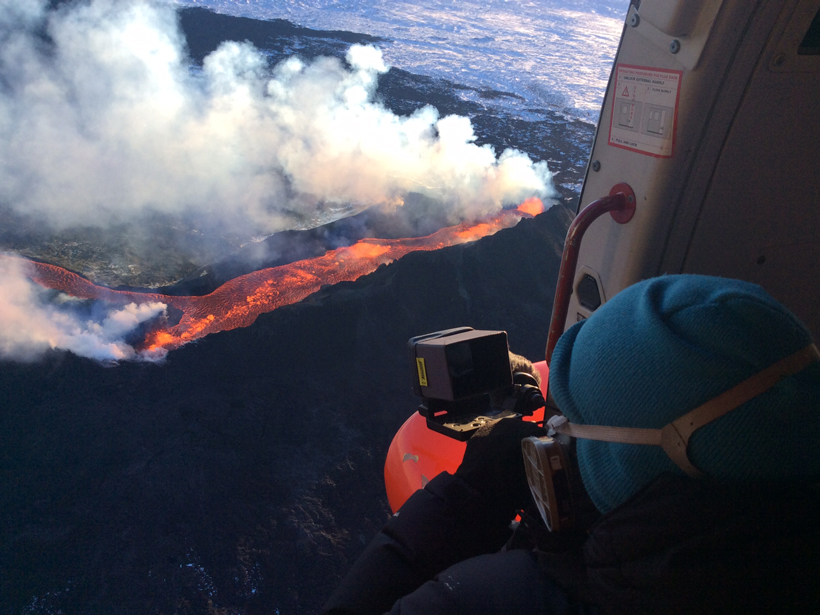

During the eruption, the Environment Agency of Iceland (EAI) and the Icelandic Meteorological Office (IMO) issued regular warnings about SO2 pollution and encouraged residents to remain indoors during times of heightened levels. Readings came from the volcano site and monitoring stations in cities downwind from the eruption. Also during the eruption, Ilyinskaya and her collaborators collected their own gas samples from a helicopter hovering just tens of meters above the fiery rift.

Long after the eruption had ended, when the researchers started analyzing their data along with data from monitoring stations in areas surrounding the volcano, something odd stuck out. In two cities, a small town called Reykjahlíð, 100 kilometers downwind from the eruption, and Iceland’s capital, Reykjavík, 250 kilometers downwind, the researchers noticed that on some days when monitoring stations detected low levels of SO2, their data indicated simultaneous high levels of sulfate aerosols, which arise from sulfur dioxide cooling in the air while reacting with other airborne molecules with the help of sunlight.

On those days, IMO characterized SO2 levels as safe but did not issue warnings for aerosols. The particles in aerosols are fine enough to deeply penetrate lungs, and airborne particulates may contribute globally to millions of deaths every year, the researchers noted.

“Plumerangs”

Ilyinskaya and her team found that a plume of sulfur dioxide would evolve into aerosols and travel back toward Iceland in a matter of days—they dubbed these secondary plumes “plumerangs.”

By comparing their direct observations to models of how sulfur dioxide converts into sulfate aerosols, Ilyinskaya and her team found that a plume of sulfur dioxide would evolve into aerosol particles and travel back toward Iceland in a matter of days—they dubbed these secondary plumes “plumerangs.” The researchers were stunned to see that the SO2 plumes could last long enough to “mature,” or fully convert into plumes of aerosols, Ilyinskaya said.

When Ilyinskaya mentioned the data to a colleague at EAI, he offered some anecdotal evidence: On one particular day in Reykjavík, when SO2 levels were reportedly low, residents still reported burning eyes and throats. The day was 20 September 2014. The researchers checked their data and found that a plumerang had blown in that very day.

“On at least 18 days during the 6-month-long eruption, the plumerang was in the capital city of Reykjavík, while the official forecast showed ‘no plume,’” Ilyinskaya said in a press release.

Public Health Follow-Up

The researchers are currently conducting a follow-up study to determine what kinds of health effects resulted from the plumerangs, Ilyinskaya said. In the meantime, the researchers suggest that SO2-to-aerosol conversions should be considered in future air pollution forecasts, especially considering the profuse SO2 emissions known to come from Iceland’s volcanoes.

“Now we know what to look out for, not if, but when, we get the next eruption,” Ilyinskaya said.

—JoAnna Wendel (@JoAnnaScience), Staff Writer

Citation:

Wendel, J. (2017), Volcano’s toxic plume returns as stealth hazard, Eos, 98, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO078265. Published on 20 July 2017.

Text © 2017. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.