Billions of years ago, rivers flowed on Mars through meandering streams and fanning deltas. But something happened in the planet’s history to turn it into the parched landscape it is today.

A new study published on 27 March in Science Advances reveals that Mars was wetter than previously thought just 1 billion years ago, challenging scientists’ beliefs about Mars’s climate evolution.

Water’s Imprint

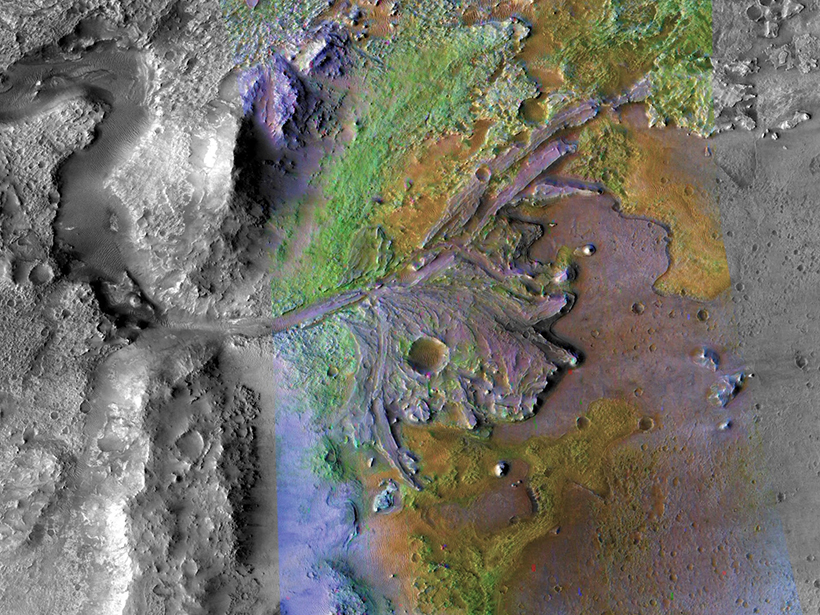

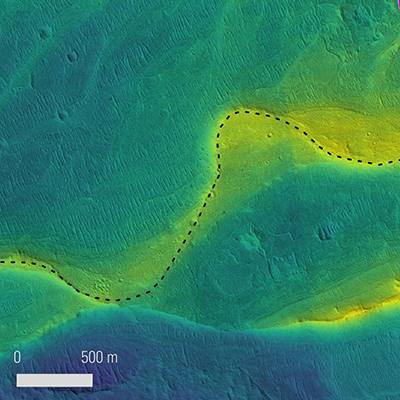

Ancient water on Mars left its mark, and the latest study makes use of these records etched into the landscape. The scientists peered at images of dried-up river and delta channels and measured their channel widths. They also traced the rivers’ shapes and calculated the distances between their meanders. Using these metrics, they inferred that Mars’s rivers once roared with intense runoff events.

Mars used to have a much thicker atmosphere, which scientists think kept the planet warm enough to have running water at the surface. But the atmosphere slowly thinned as the planet lost its protective magnetic field, and rivers that flowed later in the planet’s life, between roughly 3 billion and 2 billion years ago, probably didn’t have as much running water, the thinking goes.

Yet the new study reveals that Mars had either “intense rain or intense snowmelt” late in the planet’s history, lead author Edwin Kite from the University of Chicago told Eos.

The youngest rivers in the data set, the preserved river channels in Lyot crater, had water as recently as 1 billion years ago. The intense precipitation wasn’t just a local phenomenon, either: The study found evidence of the late-stage rivers spread around the planet.

“It’s not what we expected, and I’m not sure what it means,” Kite said of the findings.

The authors write in the paper that these results pose as a “challenge” for most existing climate models of Mars.

Thinning Atmosphere, Thickening Questions

How can scientists reconcile the new findings? One explanation, said Kite, is that Mars managed to keep water on its surface through a powerful greenhouse effect.

“Maybe there is some way of making rivers and lakes on Mars with a thin atmosphere that we’ve overlooked,” Kite noted. Possible culprits could be clouds of ice in the atmosphere or high levels of methane, he said.

The logical next step toward finding answers is to measure the size of sediment grains in ancient rivers and deltas, which will help determine more about the exact factors that shaped the channels, explained Kite.

Erin Kraal, a professor at Kutztown University of Pennsylvania who was not involved in the research, said the study reveals “another important and complex” clue of past climate.

“Determining the water budget and timing is a linchpin in establishing the climate history,” she explained. She calls for the results to be integrated into atmospheric models of Mars and compared with geochemical data at its surface.

Timothy Goudge, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin not involved in the study, told Eos that the research gives scientists “testable questions” for future studies. He’s particularly interested in future plans by NASA to visit ancient riverbeds, like the planned exploration of Jezero crater by a rover in 2020.

—Jenessa Duncombe (@jrdscience), News Writing and Production Intern

Citation:

Duncombe, J. (2019), What ancient rivers on Mars reveal about its “great drying”, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO119487. Published on 27 March 2019.

Text © 2019. AGU. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.