More than 1 million metric tons of discarded munitions lie scattered across the floors of the North and Baltic seas. As these devices corrode, they are releasing carcinogens and other toxic chemicals into the marine environment. Scientists monitoring pollution have found that these chemicals are now ubiquitous in some German Baltic waters.

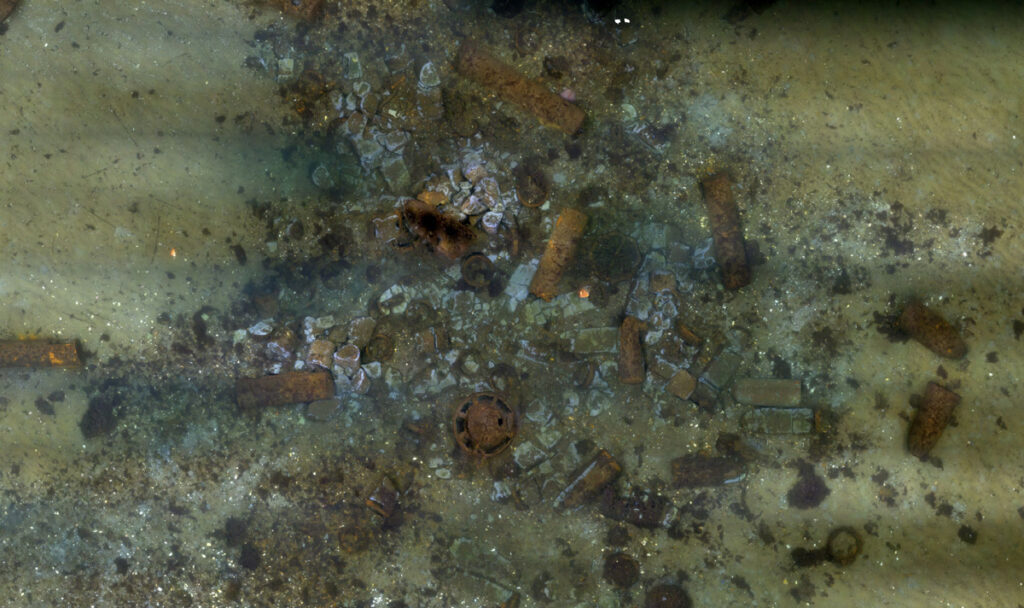

Most of the explosives were dumped intentionally at the end of World War II, when Allied nations, burdened with massive stockpiles from both the defeated Axis and their own arsenals, found the fastest and cheapest demilitarization solution in the sea. Aerial bombs, torpedoes, depth charges, and small-caliber munitions were dumped overboard at designated sites. In German waters alone, 1.6 million metric tons of ordnance were discarded. Roughly 300,000 metric tons lie in the German Baltic Sea and the rest in the German North Sea.

In a recent study, researchers found that the chemicals not only are escaping their enclosures, but also are spreading beyond the original dump sites. Analysis of water samples collected in 2017 and 2018 from the Bay of Kiel and the Bay of Lübeck in the German Baltic revealed ammunition-related chemicals in nearly every sample tested, even those collected tens of kilometers away from the main dump sites. Pollution was also present in sediments and suspended particles closer to the most polluted areas.

The levels of pollutants, in the range of tens of nanograms per liter, are not considered toxic for humans or marine life, but scientists anticipate an increase in the future. The findings were published in Chemosphere.

“This is the first time we’ve seen such a large-scale spread of contamination from dumped chemicals, whether munitions or industrial waste,” said marine scientist Aaron Beck of the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, in Germany. Beck, the first author of the study, added that he was surprised by how pervasive the pollution is.

Beck and his colleagues applied geophysical techniques including underwater sonar to map the dump sites and locate the explosive devices with accuracy. The maps helped the team analyze pollution distribution and could be used to plan the recovery and disposal of the devices.

From Actual Bombs to Ecological Time Bombs

Most of the dumped explosives contain TNT (2,4,6-trinitrotoluene), RDX (1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine), and DNB (1,3-dinitrobenzene). “The problem with these ammunition compounds is that they are not only toxic but also carcinogenic,” said Edmund Maser, a toxicologist at the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein in Kiel, who wasn’t involved in the new study. For toxic substances, it’s relatively easy to define a threshold at which they aren’t harmful. For cancer-causing compounds, risk definition isn’t as clear, because though the probability of developing cancer increases with exposure, a totally safe level cannot be defined. Technically, “one single molecule could cause cancer,” Maser explained.

“The situation may become different if corrosion continues.”

Monitoring programs in the Baltic have shown that near sunken ships loaded with explosives, fish have much higher rates of liver cancer and liver anomalies—up to 60%, compared with an average of around 1% for the general population.

At this point, however, the pollutant levels found in seafood in the region are still considered safe for human consumption. “The situation may become different if corrosion continues,” Maser said. “Maybe then it can reach levels where the human seafood consumer might be affected.”

The situation is different for marine life, which is chronically exposed to these pollutants. “We know that exposure during the whole life or during several years can cause toxic effects even at lower concentrations,” Maser said. Research has shown that mussels in the dumping areas suffer from oxidative stress and have activated defense genes to protect against it.

Continued corrosion could become an ecological threat, decreasing marine populations and diversity. The explosives add to an existing cocktail of pollutants that routinely make their way into the sea, including microplastics, pharmaceuticals, and endocrine disruptors.

Long-Lasting Pollution

Given the known inventory of explosives, if release rates are maintained, “we’ve calculated that these levels [of toxic chemicals] could be sustained for the next 800 years,” Beck said.

“I don’t see much of a scenario where the problem improves.”

However, most evidence suggests that the release rate will increase as the munitions’ metal casings continue to degrade. The researchers observed a variety of preservation states of these casings. Some appear entirely intact, whereas others have corroded rapidly and virtually disappeared. Beck thinks that changes in the quality of the steel used in casings contributed to this variability. As the war progressed, quality materials became scarce, and it’s hard to know now the exact recipes which with these housings were made. That contributes to the unpredictable state of the munitions’ deterioration.

The team noted that an increase in water temperatures due to climate change could lead to faster dissolution of the explosives and corrosion of the casings. An increased number of storms could also contribute to the dissemination and faster degradation of the munitions.

“I don’t see much of a scenario where the problem improves,” Beck said.

—Javier Barbuzano (@javibar.bsky.social), Science Writer

8 April 2025: This story has been updated to correct the type of ordnance in an image and clarify chemicals coming from ordnance in the Baltic Sea.