The greenhouse gas, methane, is produced by both natural processes and human activities. While there has been much attention paid to curbing anthropogenic emissions, a changing climate will likely increase the production of natural methane. In an open access article recently published in Reviews of Geophysics, Dean et al. [2018] describe the ways in which biological, geochemical, and physical systems influence methane concentrations and explore how methane levels in natural systems may alter in a warming climate. Here the authors answer some questions about the sources and significance of methane, and indicate some future research directions.

How does methane effect the Earth’s climate?

Methane (CH4) is a greenhouse gas that is much stronger than carbon dioxide (CO2), 34 times stronger if compared over a 100-year period. While concentrations of methane in the atmosphere are about 200 times lower than carbon dioxide, methane was responsible for 60% of the equivalent radiative forcing caused by carbon dioxide since the onset of the Industrial Revolution. Methane’s presence in the atmosphere can also affect the abundance of other greenhouse gases, such as ozone (O3), water vapor (H2O), and carbon dioxide.

What are the primary natural and anthropogenic sources of methane?

The main natural sources of methane are wetlands and freshwater systems (rivers and lakes). The main sources of anthropogenic methane are agriculture (such as cattle farming) and waste (such as landfills), and methane derived from the fossil fuel industry. Anthropogenic sources are slightly larger emitters of methane to the atmosphere compared to natural sources.

How have methane levels in the atmosphere changed over time?

Direct records of atmospheric methane concentrations only go back about 800,000 years. During this time methane concentrations have generally varied between 300 and 800 parts per billion. Since the onset of the Industrial Revolution in about 1750, however, atmospheric methane concentrations shot up to about 1800 parts per billion and are continuing to rise.

Between 2000 and 2007, atmospheric methane concentrations appeared to stabilize, leading to sustained debate regarding the main drivers of atmospheric methane. Crucially, after 2007 atmospheric methane concentrations began to rise again and current measurements suggest that atmospheric methane concentrations will continue to increase.

It remains vital that we are able to identify the cause(s) of this rise in order to address emissions of this critical greenhouse gas. Particularly important is curbing emissions from human activities, namely agriculture and the fossil fuel industries. One key example of this, currently, is the identification and mitigation of leaking natural gas infrastructure.

Which natural systems are most vulnerable to climate change and may significantly influence methane emissions?

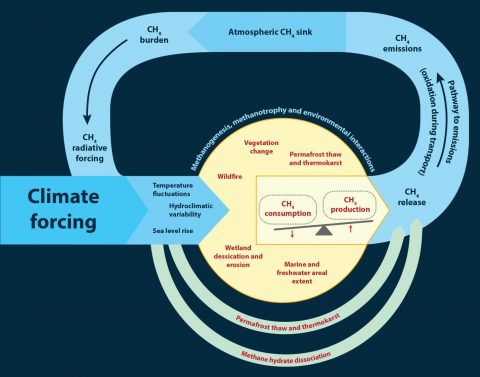

The biggest natural emitters of methane are wetlands and lakes, both of which are affected by the impacts of climate change, namely increased temperatures and changing hydrology. The balance between methane production and its oxidation within these environments before it can be released to the atmosphere, both of which are affected by temperature and hydrology, is crucial to understanding the response of these systems to climate change.

While not the largest emitters, permafrost systems (underlain by soils that remain frozen throughout the year due to cold local temperatures) are highly vulnerable to climate change. The proportion of methane emitted from such systems may increase significantly in a warmer future as the previously frozen organic carbon-rich soils are thawed out, making this material available for methane producing microbes.

What are some of the unresolved questions in this field where additional research, data or modeling is needed?

In the short-term, a key issue that needs resolving is the mismatch between global methane budgets from top-down (derived from atmospheric measurements) and bottom-up (derived from measurements of methane emissions at the land surface from different methane producing environments) approaches. This requires collecting more data at high resolution in time and space, and the use of isotopes to bridge top-down and bottom-up observations to identify methane sources across these measurement scales.

In the longer-term, a crucial question that remains is whether methane oxidation in natural environments can match potentially increased methane production in response to predicted climate change. Answering this question requires observations and modeling at a wide range of scales from the microbial- to the global-scale. This should also involve bringing together researchers across these disciplines, particularly linking geophysicists and geochemists with microbiologists.

—Joshua Dean, Department of Earth Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, The Netherlands; email: [email protected]

Citation:

Dean, J. (2018), Methane, climate change, and our uncertain future, Eos, 99, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EO095105. Published on 11 May 2018.

Text © 2018. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.