This year marks the sesquicentennial anniversary of the end of the American Civil War, a conflict that Abraham Lincoln called a “mighty scourge.” It was one of the most poignant periods in U.S. history, laying bare political, economic, social, and moral divergence between Northern and Southern states. The cause of the divergence that led to war was slavery [e.g., McPherson, 1988, chap. 3]—an institution that, by the 19th century, had been effectively abolished in the North but remained firmly entrenched in the South.

War erupted in 1861 after a confederacy of Southern states declared secession from the Union of the United States. When the war finally ended in 1865, the Union had prevailed, and afterward, slavery was abolished throughout the United States. This outcome was obtained at the cost of 750,000 American lives and substantial destruction, especially in the South [e.g., Gugliotta, 2012].

In 1865, the same year the war ended, the American landscape artist Frederic Edwin Church unveiled Aurora Borealis (pictured above), a dramatic and mysterious painting that can be interpreted in terms of 19th century romanticism, scientific philosophy, and Arctic missions of exploration. Aurora Borealis can also be viewed as a restrained tribute to the end of the Civil War—a moving example of how science and current events served as the muses of late romantic artists [e.g., Carr, 1994, p. 277; Avery, 2011; Harvey, 2012].

Background and Style

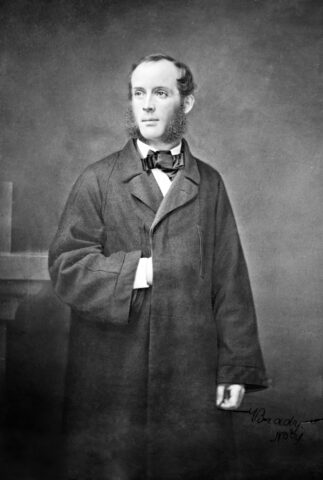

Frederic Edwin Church was born in 1826 in Hartford, Conn. His family’s wealth enabled him to pursue his interest in art from an early age. When Church was 18, a family friend introduced him to Thomas Cole, a prominent landscape painter who had founded an important American romantic artistic movement known as the Hudson River School [e.g., Howart, 1987; Warner, 1989].

With Cole as his tutor, Church learned to paint landscapes in meticulous detail, emphasizing natural light. Other prominent artists within the Hudson River School included Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran, but Church became perhaps the school’s most technically accomplished artist [e.g., Huntington, 1966]. In 1849, Church became the youngest artist ever elected as an associate of the National Academy of Design. Public showings of Church’s major works were often accompanied by advance publicity and fanfare.

Church was well known for painting large panoramas with waterfalls, sunsets, and high mountains—scenes that appealed to many Americans of the 19th century. The United States was, at the time, seemingly destined for territorial expansion. And although the vastness of untamed wilderness was slowly diminishing, daily life for most Americans remained relatively close to nature. The majority of Americans lived in the rural countryside and worked on farms. Even for those living in cities, the starry beauty of the nighttime sky had not yet been completely obscured.

The Influence of Humboldt

Church’s attentive depiction of nature on canvas was inspired in no small part by Alexander von Humboldt, the great Prussian geographer and explorer, who promoted a holistic view of the universe as one giant interacting system. In the early 19th century, Humboldt was a celebrity, and it is noteworthy that Church’s personal library included a copy of Humboldt’s masterwork Kosmos [e.g., Baron, 2005]. A multivolume treatise, Kosmos covers an amazing diversity of subjects, many of them scientific but some also historical and cultural. There is even a section devoted to aurorae, which Humboldt understood (correctly) to be related to magnetic storms.

Like other romantic intellectuals of the 19th century, Humboldt believed that one could obtain inspiration and understanding of one’s place in the world by studying the cosmos and reflecting on its grandeur [e.g., Walls, 2009]. Humboldt devoted an entire chapter in Kosmos to landscape painting, which he said “must be a result at once of a deep and comprehensive reception of the visible spectacle of external nature, and of [an] inward process of the mind” [Humboldt, 1850, part I.II]. In other words, landscape painting can facilitate a contemplation of nature that Humboldt believed could be personally beneficial.

In his own continuous search for the sublime, Church turned his attention northward.

From 1799 to 1804, Humboldt traveled extensively in South America, mapping rivers, measuring mountains, and cataloging flora [e.g., Gillis, 2012]. Half a century later, Church followed some of Humboldt’s journeys, visiting many of the places Humboldt had visited, painting many of the same mountains and waterfalls that Humboldt had seen and sketched. Subsequently, in his own continuous search for the sublime, Church turned his attention northward, visiting Labrador, Canada, in the summer of 1859, where he sketched and painted icebergs and, not surprisingly, witnessed beautiful aurorae [Noble, 1861].

The Scene of Aurora Borealis

After the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, it would have been reasonable to predict Union victory in the American Civil War [e.g., McPherson, 1988, chap. 21]. In that same year Church began working on Aurora Borealis, assembling elements taken from different sources to form what is essentially a fictional scene [e.g., Truettner, 1968]. The painting, oil on canvas, is physically large: 143 × 212 centimeters. From an elevated and exhilarating perspective, we look out over a far northern, nighttime scene. Auroral light casts a pale illumination across a still world of barren mountains and a broad expanse of frozen sea. In the foreground, we see a small boat and a man with a dog-drawn sled.

Church never saw the landscape presented in Aurora Borealis. As it happened, Church taught the arctic explorer Isaac Israel Hayes the fine arts of drawing and painting. Church and Hayes became close friends, and the landscape in Aurora Borealis is based on drawings made by Hayes during an 1860 expedition [e.g., Truettner, 1968]. The ice-locked boat is Hayes’s schooner, the United States [Hayes, 1867, p. 211]. The mountains are a depiction of those on Ellesmere Island, the northernmost land in Canada. And in the background is a sharp peak that Hayes called Church Peak (81.26°N, 65.62°W), named in honor of his friend and art instructor [Hayes, 1867, p. 351] .

With respect to the auroral light depicted in Aurora Borealis, Church might very well have recalled the brilliant displays of aurora borealis that came before the war in August and September 1859. These were caused by solar and magnetic storm events that are now collectively called the Carrington event [e.g., Clark, 2007].

The 1859 aurorae were widely reported in newspapers and seen across the United States, even in the South, where some observers interpreted them as portending war [e.g., Love, 2014]. Still, it is worth recognizing that Church would have seen aurorae many times while living in New England and New York and during his trips to Labrador. Indeed, the shape of the auroral arc in Aurora Borealis is taken from a sketch that Church made in September 1860 while visiting Maine [e.g., Truettner, 1968, note 36].

Artistic License

When Aurora Borealis was first publicly displayed in March 1865, a reviewer described its depiction as “beauteously strange aerial phenomena … rendered with wonderful vividness and delicacy of feeling” [Bayley, 1865, p. 266]. Church’s artistic abilities were certainly impressive, but we can recognize that Church did not necessarily strive to depict nature with rigorous accuracy. He was an “interpreter of nature, rather than a transcriber” [Warner, 1989, p. 185].

Church was an “interpreter of nature, rather than a transcriber.”

Church painted the rays of the aurora converging toward a vanishing point on the horizon. Normally, auroral rays result from charged particles descending from the magnetosphere into the atmosphere, guided along the field lines of the Earth’s magnetic field. On their way down, collisions between these particles and atmospheric molecules cause the charged particles to glow. The magnetic field lines descend at high latitudes and converge toward the magnetic poles. Thus, normal artistic perspective would show aurorae near the horizon as curtains with vertical rays; otherwise, auroral rays would appear to converge to a vanishing point high overhead, essentially orthogonal to the depiction chosen by Church.

Perhaps Church was using the rays of the auroral arc to convey the sense of a broad panorama, with us, the observers, at its center. Or he may have simply intended to draw our attention from the heavens above down to the Earth and humankind below.

Some of Church’s manipulation of form might reflect the fact that Aurora Borealis was executed simultaneously with another painting, Rainy Season in the Tropics, which shows a double rainbow over a Central American mountainscape. The two paintings, both crowned by curving arcs of light, are complementary [e.g., Avery, 2011; Harvey, 2012]—one shows night, the other day; one depicts a high-latitude scene, the other low; one is cold, the other warm.

Another curiosity is the color palette of Aurora Borealis. The dominant color in auroral light is usually green, emitted by atomic oxygen at a wavelength of 557.7 nanometers. Yet Church largely omits green from Aurora Borealis, placing emphasis on red, blue, and yellow light. Furthermore, auroral light is usually seen as a sort of vertical stack of colors, with red light on top, blending into green and then blue and sometimes dark red on the bottom. In contrast, Church shows an auroral arc with red light at the same horizontal level as blue.

Interpreting Aurora Borealis as a Civil War Icon

Aurora Borealis is thick with symbolism. The auroral arc of light encompasses a dark void in the sky that might represent the uncharted north or some greater unknown. Below this, and at the foot of dark mountains, Church depicts humanity—the forlorn man with his sled dogs—as tiny and seemingly insignificant (see detail). The challenge of exploring the unknown is represented by the placement of the schooner: locked in the ice, facing a vast frozen sea. Its crew might be in search of the Northwest Passage or the mythical ice-free polar sea [Hayes, 1867]. They may or may not succeed in their search; regardless, the universe will carry on. Still, despite seemingly overwhelming challenges, there is a small sign of optimism: light shines through a window on the ship.

It is not much of a stretch to interpret the painting as a tribute to an expected end of the American Civil War.

Such a summary is straightforward and consistent with traditional romantic ideas, but it is possibly not the whole story behind Aurora Borealis. Some art historians see the social and political tension and turbulence in mid-19th century America reflected in landscape paintings of the era [e.g., Harvey, 2012]. Although Church never commented on the meaning of his paintings and he left few written records, we can contemplate the possibility that Church intended to paint something rather profound in Aurora Borealis. Considering the circumstances of the time, it is not much of a stretch to interpret Aurora Borealis as a tribute to an expected end of the American Civil War.

If Church meant the light in Aurora Borealis to be a metaphor for the end of the Civil War, then he was in the company of poets. Herman Melville, author of the epic novel Moby Dick, penned a melancholy poem on the course of the war entitled “Aurora-Borealis” [Melville, 1866], writing of a supernatural march of a “million blades that glowed” and which had been disbanded with the rising Sun of the war’s end. Christopher Cranch, a preacher and fellow painter from the Hudson River School, wrote of the injury and seeming necessity of the war in “The Dawn of Peace” [Cranch, 1890]: “We wake to see the auroral splendors stream across the battle smoke from opening skies. The demon, shrieking, tears us as he flies exorcised from our wrenched and bleeding frame. O costly ransom!”

Church certainly harbored nationalistic feelings. This is vividly demonstrated in his 1861 painted sketch entitled Our Banner in the Sky, where an American flag is seen as a miraculous materialization in the sky from white clouds, the red light of a sunrise, a convenient patch of blue sky, and a bright star. It was an unsophisticated, but popular, piece, resonating with the flag adulation emotion that had swept through the North soon after the war started [e.g., Burke, 1982; Avery, 2011]. But the war did not, as many had hoped, come to a quick and tidy end. Instead, it continued on until 1865, after the toll of destruction and death had reached frightening levels.

The message of Church’s painting is subdued, even ambiguous.

In contrast to the overtly nationalistic Banner, the message of Aurora Borealis is subdued, even ambiguous [e.g., Avery, 2011]. A visitor to Church’s studio who saw Aurora Borealis in March 1865 likened it to the frozen ninth circle of Dante’s Inferno, a terrible place for those who have committed treachery; the same visitor even suggested that such might be the fate for the entire nation [Barbone, 1865]. Some have suggested that the drapery of light in Aurora Borealis represents the American flag [e.g., Carr, 1994, p. 277]. If so, then it has been unfurled across a cold and barren landscape, not in extravagant celebration of the war’s anticipated end, but in subdued and somber recognition of the reality of postwar desolation and an uncertain future.

Acknowledgments

I thank C. A. Finn, E. J. Rigler, J. McCarthy, and J. L. Slate for reviewing a draft manuscript. I thank W. S. Leith for useful conversations.

References

Avery, K. J. (2011), Rally ’round the flag: Frederic Edwin Church and the Civil War, Hudson River Valley Rev., 27(2), 66–103.

Barbone (1865), Art in New York, March 18, Daily Evening Bull. (Philadelphia), 21 March, 8.

Baron, F. (2005), From Alexander von Humboldt to Frederic Edwin Church: Voyages of scientific exploration and creativity, Int. Rev. Humboldtian Stud., 6(6), 1–15.

Bayley, W. P. (1865), Mr. Church’s pictures, Art J., 4, 265–267.

Burke, D. B. (1982), Frederic Edwin Church and “The Banner of Dawn,” Am. Art J., Spring, 39–46.

Carr, G. L. (1994), Frederic Edwin Church: Catalogue Raisonne of Works of Art at Olana State Historic Site, vol. 1, Text, 565 pp., Cambridge Univ. Press, New York.

Clark, S. (2007), The Sun Kings: The Unexpected Tragedy of Richard Carrington and the Tale of How Modern Astronomy Began, 211 pp., Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, N.J.

Cranch, C. P. (1890), The Bird and the Bell, 327 pp., Houghton, Mifflin, Boston, Mass.

Gillis, A. M. (2012). Humboldt in the New World, Humanities, 33(6), 18–21, 41.

Gugliotta, G. (2012), New estimate raises Civil War death toll, New York Times, 2 April.

Harvey, E. J. (2012), The Civil War and American Art, 352 pp., Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, Conn.

Hayes, I. I. (1867), The Open Polar Sea, 407 pp., Sampson Low, Son, and Marston, London.

Howart, J. K. (Ed.) (1987), American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School, 347 pp., Metropolitan Mus. of Art, New York.

Humboldt, A., von (1850), Cosmos, English translation of Kosmos by E. C. Otté, vol. 2, Harper, New York. [Reprint, Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, Md., 1997.]

Huntington, D. C. (1966), The Landscapes of Frederic Edwin Church, 210 pp., Braziller, New York.

Love, J. J. (2014), Auroral omens of the American Civil War, Weatherwise, 67(5), 34–41, doi:10.1080/00431672.2014.939912.

McPherson, J. M. (1988), Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, 952 pp., Oxford Univ. Press, New York.

Melville, H. (1866), Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War, 272 pp., Harper, New York.

Noble, L. L. (1861), After Icebergs with a Painter, 336 pp., D. Appleton, New York.

Truettner, W. H. (1968), Genesis of Frederic Edwin Church’s Aurora Borealis, Art Q., 31, 266–283.

Walls, L. D. (2009), Introducing Humboldt’s Cosmos, Minding Nat., August, 3–15.

Warner, C. D. (1989), An unfinished biography of the artist, in Frederic Edwin Church, edited by F. Kelly, pp. 174–199, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Author Information

Jeffrey J. Love, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colo.; email: [email protected]

Citation: Love, J. J. (2015), Aurora painting pays tribute to civil war’s end, Eos, 96, doi:10.1029/2015EO035713. Published on 24 September 2015.

Text not subject to copyright.

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.