Geoscientists know well the value of their work and their discipline. Innovative geoscience research and education are critical to addressing the major societal challenges we face today, from sustainably producing sufficient energy and resources, to building communities resilient to natural hazards, to adapting to and mitigating the effects of climate change [Summa et al., 2017; Tewksbury et al., 2013]. And geoscientists bring a unique set of tools to these challenges, including methods for testing hypotheses against Earth observations, capabilities for spatial and temporal reasoning across scales, and systems thinking that recognizes interconnections among Earth system processes [Manduca and Kastens, 2012].

Unfortunately, the value of geoscience is not always as obvious to others. Because it is often absent from high school curricula, geoscience is a discipline that many people discover for the first time in college [Levine et al., 2007; Stokes et al., 2015]. Geoscience departments work hard to attract students through introductory courses that focus on popular subjects such as volcanoes and earthquakes, dinosaurs, and what makes our planet habitable. Still, these departments are typically smaller than other science departments.

Twenty years ago, Lisa Rossbacher and Dallas Rhodes described a tension on college campuses between groups of departments considered essential (such as English, math, biology, and history) and those whose existence requires continual justification. Rossbacher and Rhodes, both geologists themselves, put geoscience departments in the second category because they are relatively small, expensive to run (think of the high costs of field trips, equipment, and sample storage space), and sometimes wade into topics that turn out to be controversial in the public eye (e.g., climate change, hydrofracking, and water quality).

The geosciences have evolved substantially in the past 20 years, but the perception that geoscience programs are nonessential to universities remains.

Long-standing links between geoscience programs and the extractive industries that have traditionally hired many geoscientists—along with the boom-and-bust cycles of this hiring—also influence perceptions of the discipline. These links can cause large swings in the number of students interested in taking introductory courses and pursuing geoscience degrees, as seen in the 1980s and again in recent years [Keane, 2022].

The geosciences have evolved substantially in the past 20 years, fueled by technological advances, interdisciplinary approaches, and a rapidly changing planet, but the perception that geoscience programs are nonessential to universities remains. As a discipline, geoscience also continues to struggle to attract and retain a diverse range of students and to overcome an emphasis on ableism and a history of exclusion. These issues pose challenges to geoscience departments, programs, and courses (both undergraduate and graduate), leaving them vulnerable to restructuring or elimination—especially as many universities face declining enrollments and shrinking budgets—and creating pressure to rebrand to attract more students.

But it does not have to be that way. Departments that not only know their value but also can communicate it within and beyond their respective campuses; that have well-designed courses and curricula that support their students’ interests, growth, and success; and that have a clear vision of what they do well and how they can improve are far better positioned to adapt and thrive in changing academic climates.

Such departments provide models of success for others in their institutions and in the discipline. Achieving these aspirations, however, often requires examining deeply entrenched habits and implicit biases and building a common vision and a will to act. Those processes can be difficult even when time is set aside for them. So where can departments turn for help?

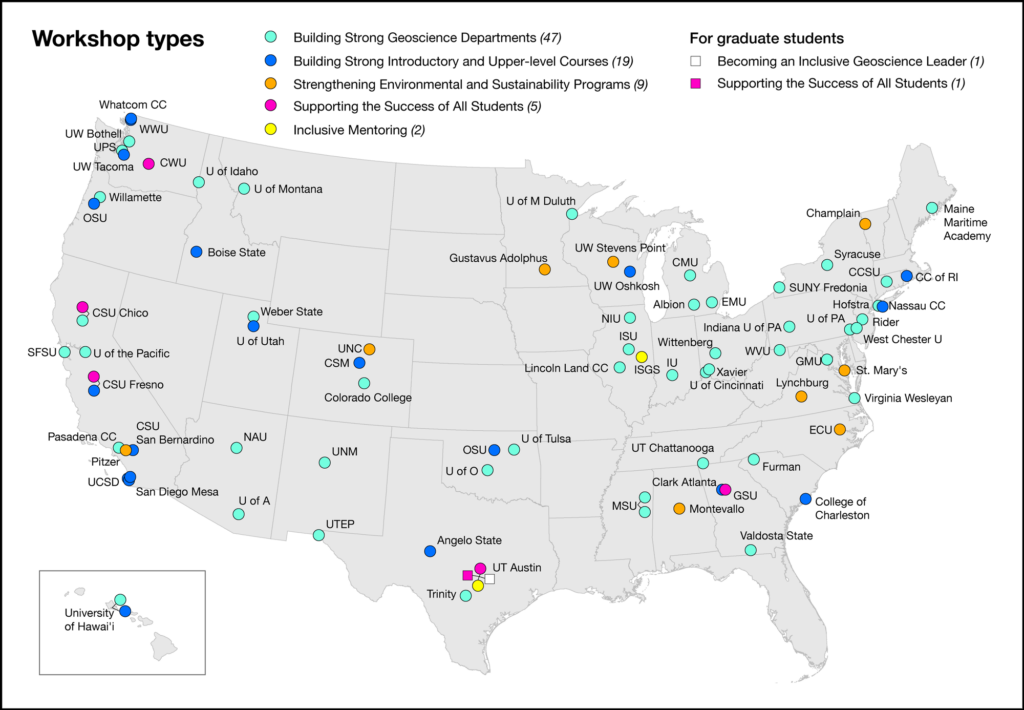

Since 2014, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers’ (NAGT) Traveling Workshops Program (TWP) has run workshops for more than 80 departments and programs at many types of higher education institutions in 33 U.S. states (and one other country) to support them in building stronger and more inclusive cultures, curricula, and courses (Figure 1). The TWP, one component of NAGT’s long-running professional development programming, relies on educators with diverse expertise and experience to lead participants through a highly customized facilitation process that better enables them to navigate change.

As leaders of the TWP and facilitators ourselves, we find that supporting individuals and departments through this process is fulfilling and rewarding. More important, however, we have seen that the TWP works—participants leave the workshops energized and motivated, with clear and achievable plans for strengthening their programs.

Building Potential for Successful Change

The impetus for change and the need for support within departments can stem from a variety of sources. In our experience, we have seen interest in the TWP come from the following sources:

- programs needing to restructure after several faculty retired and/or new faculty arrived

- programs facing shifts in student interest from traditional geology topics to environmental geoscience and sustainability

- departments under pressure to increase course enrollments and numbers of majors

- a system of community colleges wanting to improve the quality and student appeal of its geoscience instruction

- a cross-departmental environmental sciences program seeking to demonstrate its value to students, parents, faculty, and its institution

A program leader’s commitment to support—and to colead—change efforts is critical to success.

Anyone from a department, program, or institution can request assistance from the TWP by providing information about their group and what they hope to accomplish. The applicant need not have a formal leadership role, although their department chair (or other relevant leader) must play a role in the process. Indeed, a program leader’s commitment to support—and to colead—change efforts is critical to success [e.g., Graham, 2012].

The TWP management team matches facilitators to a request on the basis of availability and relevant expertise and experience. Facilitators are themselves geoscience or environmental science faculty who are brought into the program because of their wide-ranging experience in successfully navigating changes in their own institutions and in supporting others in their planning.

The matched facilitators, who work in pairs, meet with the applicant and department leader to begin planning the workshop, which typically takes place over 2 days. They use a backward design approach [Wiggins and McTighe, 2005], first defining desired outcomes and learning about the department’s culture and history before determining what steps are needed for the program to achieve those outcomes.

In these initial discussions, facilitators also learn more about the broader institutional forces at play. They typically meet with a dean, provost, or other leader to better understand the administration’s perspective on the department, how it is perceived within the college or university, how its challenges fit into the bigger picture of the institution, and what the hopes are for change. In our experience, these conversations are highly productive and positive: Deans and provosts want their departments to thrive and are encouraging of outside facilitation—frequently even footing the bill ($5,000 plus travel for the facilitators) for the workshop.

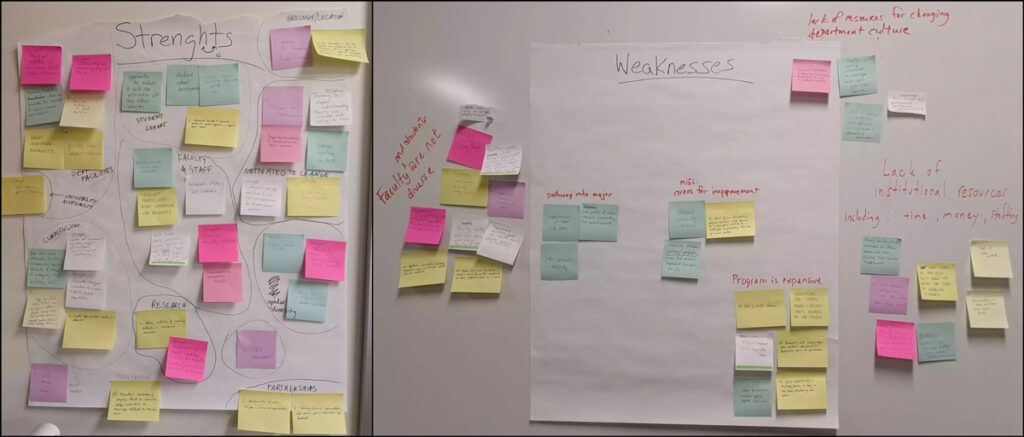

These planning conversations help the facilitators develop a customized workshop agenda that meets the needs of the department or program through engagement in time-tested activities. Examples of activities that TWP leaders have developed include a strengths-weaknesses-opportunities-threats (SWOT) analysis, a process for developing course- and program-level learning outcomes that begins by envisioning a successful student, and a reflection about identity and implicit bias that leads into developing strategies for attracting and supporting all students.

How the Workshops Work

A key focus of the TWP is bringing everyone in a department or program together to develop a shared vision and goals from which actions can emerge. This critical level of engagement is why we travel to bring the workshop to the program in need. (Most workshops happen in person, although we also offer virtual programming for dispersed groups.) Having departmental representatives attend an off-site workshop and then report back to their larger group does not achieve the same result, primarily because there is no opportunity to build a common vision, which can leave many uninvested in the process.

The needed conversations can be difficult and fraught, surfacing deeply entrenched feelings and power dynamics.

In addition, the needed conversations can be difficult and fraught, surfacing deeply entrenched feelings and power dynamics. It is common for department chairs to tell us ahead of time of distinct groups in their departments that do not see eye to eye. Or sometimes we learn that newer faculty don’t contribute in faculty meetings or are talked over by longer-tenured colleagues. These dynamics are why we facilitate workshops: We provide objective leaders who ensure that everyone is heard and that discussion remains collegial and productive.

To lay the groundwork for a productive workshop, participants complete “homework” in advance so they are prepared for the discussions ahead and so that during the workshop, they can focus on the group interaction. For workshops focused on strengthening departments overall, the homework might entail exploring demographic data about their institution and program, revisiting their program’s mission and goals, and reflecting on the impacts they want to have on students. We often ask individuals to complete a self-assessment about their department that is designed around established characteristics of a thriving department. With these results, we can highlight where there is agreement and disagreement and use those insights as starting points for discussion. For workshops focused on course design, we also ask participants to reflect on demographic data about their students, the learning outcomes of their courses, and how their courses fit into the curriculum.

Workshop activities are interactive and discussion rich, and we apply many of the same strategies we use in our own teaching to ensure that all participants have the opportunity to contribute. Specifically, we create small groups to work on and report out on tasks; we ask everyone to reflect on activities, write down their thoughts, and then share them; and we limit individual contributions so that people who are more talkative cannot dominate conversations. In one case in which we knew a department was feeling collectively pessimistic, we held up an image of a downward spiral when the conversation was going in a negative direction. Gently calling out nonproductive discussion allowed us to get back on track.

Facilitators help participants clarify and prioritize concrete steps—and who will take them—that will most effectively contribute to the group’s desired outcomes.

Following the first day of discussions, participants complete a “road check”—an anonymous three-question evaluation so the facilitators can get a sense for how participants feel the workshop is going, respond to concerns, and adjust the plan for the next day if needed.

Regardless of the workshop theme, a major focus of the second day is on action planning: The facilitators help participants clarify and prioritize concrete steps—and who will take them—that will most effectively contribute to the group’s desired outcomes. Examples of such actions include updating a department’s website and social media presence to increase program visibility; creating or restructuring an advisory board to better represent current job opportunities and priorities; and submitting a proposal for new program learning outcomes and a major curriculum to an institution’s curriculum committee.

Measures of Success

At the end of the scheduled agenda, participants complete an end-of-workshop evaluation that asks respondents to rate aspects of the workshop and their overall satisfaction and to answer open-ended questions that allow for more explanation. The feedback we have received from more than 500 of these evaluations has been overwhelmingly positive (an average overall satisfaction rate of 8.9 out of 10), with comments often focusing on the benefits of the facilitation and how it enabled input from everyone involved.

One participant commented, “Having attempted to steer strategic planning discussions and action planning in our department for a while, it was tremendously helpful to have skilled facilitators, knowledgeable about the issues we are facing, to guide us.”

Another said, “The workshop provided the (very) necessary space for my [department] to focus on future hires, curriculum change, and relevance within our institution. All of the [department] faculty were able to agree on specific goals and actions related to these themes…which definitely feels like progress.”

Unfortunately, we do not have a formalized way to track long-term outcomes of individual workshops, nor can we directly compare the efficacy of the TWP with other interventions (our knowledge of higher education and discipline-specific professional development suggests that these comparisons are hard to come by). However, informal follow-ups and other kinds of feedback from participating programs have provided additional confirmation of the program’s efficacy.

A number of programs have requested multiple workshops, sometimes the same type of workshop after several years have passed, sometimes a different type (Figure 1). In such requests, applicants typically mention how valuable the first workshop was to their department or program and that they knew where to turn for additional support.

When opportunities arise, we also check in informally with departments (perhaps connecting with a department chair at a meeting) to learn how they are doing in implementing their action plans. Almost universally, the institutional landscape has continued to change, but they frequently report being better equipped to navigate and respond to that change because of the work their members did together in the workshop and that building a shared vision was key to their success.

Adapting to Meet Needs

By analyzing the participant evaluations and facilitator reflections together, we can identify common themes and make changes as needed, creating a process of continuous improvement in the Traveling Workshops Program.

Facilitators also share their own reflections on workshops with the TWP leadership team, focusing on what worked well, what didn’t quite go as planned, and what could be improved to better support the group they worked with. By analyzing the participant evaluations and facilitator reflections together, we can identify common themes and make changes as needed, creating a process of continuous improvement in the TWP. As a result, our offerings evolve, much as departments and programs must, with changes in scientific disciplines, student demographics and interests, and institutional contexts. We are also responsive to community members’ input about the challenges they are facing and requests for support.

The TWP’s initial efforts were focused on strengthening departments and teaching in courses, and these two themes underlie the most common workshops we’ve offered (Figure 1). Starting in 2017, with funding from the Interdisciplinary Teaching about Earth for a Sustainable Future (InTeGrate) project, we developed two new themes: one that broadened the focus from a single department to building strong cross-campus environmental and sustainability programs and another focused on department culture and inclusivity and supporting the success of all students. At the same time, we refined and added to the two main themes to expand their relevance beyond traditional geoscience courses and programs.

More recently still, we developed two more workshops—both representing new directions and approaches—in response to community requests. In 2020, we received a request to offer programming for graduate students, with the idea of supporting future faculty in developing skills that they can bring with them. That request resulted in the development of TWP’s “Building Inclusive Geoscience Leaders” workshop designed specifically for students (Figure 1).

Then in 2023, we were asked to develop a workshop focused on inclusive mentoring. Unlike most of our workshops, which benefit from being offered in person, the “Inclusive Mentoring” workshop works very well as a virtual offering, allowing us to bring together mentors who may all be involved in a single program but are widely dispersed physically. The virtual offering also allows time between sessions for participants to enact and get feedback on some of the strategies we discuss. This past May, we expanded beyond our typical audience base at academic institutions to offer this new mentoring workshop for a state geological survey that is hosting several summer interns and sought additional support for their scientists.

As we look to the future, the TWP will continue to work with programs to address common challenges and build skills. Given our recent positive experiences with new workshop themes and repeat customers, we also plan to promote these options more specifically and add opportunities for graduate students and postdocs. We encourage anyone interested to reach out to discuss how we can provide support. By continuing to facilitate difficult discussions about needed changes and how to achieve them, NAGT’s traveling workshops are helping the geoscience community adapt to changing academic and workforce climates, giving departments and programs the tools they need to demonstrate their value and provide welcoming experiences for all students.

References

Graham, R. (2012), Achieving Excellence in Engineering Education: The Ingredients of Successful Change, 70 pp., R. Acad. of Eng., London, rhgraham.org/resources/Educational-change-report.pdf.

Keane, C. M. (2022), Geoscience enrollment and degrees continue to decline through 2021, Data Brief 2022-010, Am. Geosci. Inst., Alexandria, Va., americangeosciences.org/geoscience-currents/us-geoscience-enrollments-and-degrees-through-2021.

Levine, R., et al. (2007), The geoscience pipeline: A conceptual framework, J. Geosci. Educ., 55(6), 458–468, https://doi.org/10.5408/1089-9995-55.6.458.

Manduca, C. A., and K. A. Kastens (2012), Geoscience and geoscientists: Uniquely equipped to study Earth, Spec. Pap. Geol. Soc. Am., 486, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1130/2012.2486(01).

Stokes, P. J., R. Levine, and K. W. Flessa (2015), Choosing the geoscience major: Important factors, race/ethnicity, and gender, J. Geosci. Educ., 63(3), 250–263, https://doi.org/10.5408/14-038.1.

Summa, L., C. M. Keane, and S. Mosher (2017), Meeting changing workforce needs in geoscience with new thinking about undergraduate education, GSA Today, 27(9), 60–61, https://doi.org/10.1130/GSATG342GW.1.

Tewksbury, B. J., et al. (2013), Geoscience education for the Anthropocene, Spec. Pap. Geol. Soc. Am., 501, 189–201, https://doi.org/10.1130/2013.2501(08).

Wiggins, G., and J. McTighe (2005), Understanding by Design, Assoc. for Supervis. and Curric. Dev., Alexandria, Va.

Author Information

Anne E. Egger ([email protected]), Central Washington University, Ellensburg; also at the National Association of Geoscience Teachers, Northfield, Minn.; and Walt Robinson, North Carolina State University, Raleigh