The urgency of the climate crisis grows every year; meanwhile, disinformation and politicization have made communicating the science of climate change increasingly challenging. For the past 2 decades, such communication efforts have focused mainly on convincing people that climate change is real while also combating organized campaigns of denialism [Mann, 2012]. These efforts have largely succeeded: Polls show that the public now overwhelmingly accepts the reality of climate change. In one recent example in the United States, Leiserowitz et al. [2022] found that three quarters of those surveyed were “alarmed,” “concerned,” or “cautious” about climate change, whereas fewer than 20% were “dismissive” or “doubtful.”

Students are a vital demographic to reach as we shift the prevailing messaging of climate communication.

So although challenging climate change denial may still be necessary in some contexts, scientists, educators, and others who communicate about climate science face a new challenge: the clear gap between the public’s concern over climate disruptions and its understanding of what can be done today to affect our tomorrow. We must better convey to audiences the needed changes—in energy sources and land use, for example—and that humanity can, indeed, influence the scale of disruptions that unfold [Marris, 2021; Mann, 2021]. It is time to reorient our messaging, focusing less on predictions of future hazards as though they are foregone conclusions and instead communicating a “hopeful alarm” that simultaneously stresses the urgency of the situation and instills a sense of agency in guiding the future.

Students are a vital demographic to reach as we shift the prevailing messaging of climate communication. Not only do they represent the next generations who must face the challenges of climate change, but also when they are surveyed, students and younger people generally profess concern about the issue and interest in climate action at higher rates than older segments of the population.

Indeed, young people, including many of our own students, are hungry for information: In a 2023 survey, for example, 30% of U.S. teenagers expressed an interest in learning more about jobs related to sustainability and climate change. Meanwhile, hiring for “green jobs” has already been outpacing overall hiring in recent years, and transitioning from fossil fuels to clean energy is forecast to generate millions of jobs in coming decades. Educators and climate communicators can help meet these demands and empower students by providing specific examples of useful actions and relevant tools and opportunities to help them act constructively.

The Hopeful Alarm Approach

We must be a beacon of hope, because if you tell people there’s nothing they can do, they will do worse than nothing.

—Margaret Atwood, The Year of the Flood

If hopeful alarm sounds like Pollyannaism, rest assured it is not. We can communicate the seriousness of potential perils to humanity and nature from climate change while also offering examples and resources that model constructive engagement, much as a physician would communicate the urgency of a cancer diagnosis while outlining a path forward. That is not heedlessly optimistic—rather, it is simply pragmatic.

Worry, not fear, has been shown to encourage protective, adaptive behaviors [Marx et al., 2007]. Despair and hopelessness, meanwhile, have been documented to lead to “climate anxiety” and to sap motivation to act—indeed, fossil fuel interests deliberately promulgate widespread cynicism and “doomism” among the public as a strategy to prevent meaningful action [Coan et al., 2021].

Any message of hopeful alarm should begin by emphasizing that people have agency, both individually and collectively, to shape the future. The die is not cast: Any actions that reduce carbon emissions today will improve our future, and there are not just two possible outcomes—success or failure. Instead, there is a continuum of potential outcomes, and where we land along that continuum depends on decisions we make now and in the years to come.

Technologies and policies with the potential to reduce atmospheric carbon emissions and greatly moderate the consequences of climate change exist [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023]. Adaptation measures can also be undertaken so that future impacts are more manageable. Yet it is rare that these messages are presented clearly to the public.

Implementing these technologies, policies, and measures will be difficult and likely involve discussions, negotiations, and, ultimately, widespread buy-in, not only from lawmakers but also from the public. But if much of the public isn’t aware of the options available for dealing with the climate crisis, how are the needed conversations even to begin?

As a part of the effort to broadcast hopeful alarm, educators should reconsider climate-related content in their courses. For example, how much focus is put on messages like “Climate change is happening, and it is serious” versus “Here are solutions and ways to get involved”? We argue that in most curricula, not enough time is devoted to discussing solutions and, especially, to providing students with examples of productive action on behalf of the climate to inspire their own participation.

Bringing Climate Action into the Classroom

Many options exist by which educators can incorporate discussions of climate action into courses of different sizes, durations, and levels.

Many options exist by which educators can incorporate discussions of climate action into courses of different sizes, durations, and levels (see sidebar). Even single class sessions that include sharing examples of role models and mitigation actions can make a difference for students.

One of the easiest, yet still impactful, ways to broaden presentations of climate change is to highlight people and institutions involved in climate action: for example, activists influencing public policy, entrepreneurs bringing new products to market, and municipalities building climate resilience.

| Time Available and Course Format | Ideas for Incorporating Climate Action |

|---|---|

| Single class, lecture courses | ● Spotlight a specific person or an example of action or mitigation ● Highlight other large-scale problems that have been effectively addressed through science-based action and policy (e.g., the ozone hole via the Montreal Protocol and its amendments, which have also helped mitigate global warming) ● Invite students to pose questions about climate change |

| 1–3 classes, lecture courses | ● Detail a case study of a potential mitigation action, such as one outlined by Project Drawdown ● Have students contribute to a class-wide slide presentation of people taking action to confront or manage climate change ● Discuss jobs and careers related to climate adaptation and mitigation |

| 2–3 weeks, lecture courses | ● Have students prepare reports about a specific action or solution (see Project Drawdown for examples) ● Demonstrate effects of various potential policies on climate change projections using Climate Interactive’s EN-ROADS tool ● Guide students to contact local leaders or engage family members about issues related to climate action |

| 2–3 weeks in courses with small-class sessions | ● Visit and discuss climate action with local stakeholders, such as municipal officials, entrepreneurs, and activists ● Direct a climate negotiation simulation, using Climate Interactive’s World Climate Simulation |

| >3 weeks in a small course or a large course with lab sections | ● Calculate campus emissions budget from campus data, including for electricity, heating/cooling, and transportation ● Develop proposals to reduce campus carbon emissions, following examples such as the Shut the Sash! project |

| Entire semester in a small class | ● Facilitate internships or service learning with local stakeholders, municipal officials, or environmental organizations |

Among the individuals we highlight are Swedish activist Greta Thunberg and scientist Dr. Katharine Hayhoe, whose identification with the evangelical Christian community resonates with a particular segment of students. We share resources such as the edited volume All We Can Save [Johnson and Wilkinson, 2020] and the Not Too Late project to help show the range of people involved in climate solutions, and we encourage students to participate in youth movements such as Zero Hour and the Sunrise Movement. We also describe steps that local municipalities have taken, such as instituting climate action plans and projects to confront flooding risks exacerbated by extreme weather and sea level rise.

Classroom discussions of these individuals, movements, and institutions can be tailored to a wide variety of audiences, including students in many non-STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fields such as business, sociology, and even the arts. Such stories are empowering and breed a willingness to engage [Sabherwal et al., 2021].

Such projects make discussions of carbon emissions more concrete because they are centered around students’ own experiences.

Instructors can offer students more in-depth analysis of how carbon emissions can be targeted. For example, students can evaluate carbon-emitting activities and consider how those activities could be more efficient. Project Drawdown, which highlights dozens of specific actions across a range of sectors that reduce emissions or enhance natural carbon sinks, and Project EDDIE, which provides curricular modules and teaching activities (e.g., exploring green roofs as a solution to climate-induced precipitation increases), are great resources from which to draw. Instructors can also emphasize the rapid growth in emissions-reducing technologies using business-focused analyses to counter perceptions that controlling carbon emissions is dependent solely on government largess.

In courses in which more time is available to focus on climate action (e.g., in courses featuring supplemental laboratory sessions), students could investigate climate action plans and emissions data from their own campuses to determine where cuts could be made or propose initiatives to reduce emissions. We have, for example, directed students to calculate campus carbon emissions related to electricity, heating and cooling, and transportation. They can also compare the energy provided via conventional versus renewable sources. Such projects make discussions of carbon emissions more concrete because they are centered around students’ own experiences while also giving them valuable tools of analysis and even policy action.

The activities described above are largely directed at undergraduate and graduate students, but they can also be undertaken in secondary school classrooms and laboratories. Many, if not all, of them support education standards related to analyzing and interpreting data, using mathematical and computational thinking, and constructing explanations and designing solutions. In addition, the National Center for Science Education offers a “Climate Super Solutions” module for grade 9–12 classes that supports various Earth and space sciences core ideas.

Simulations and Service Learning

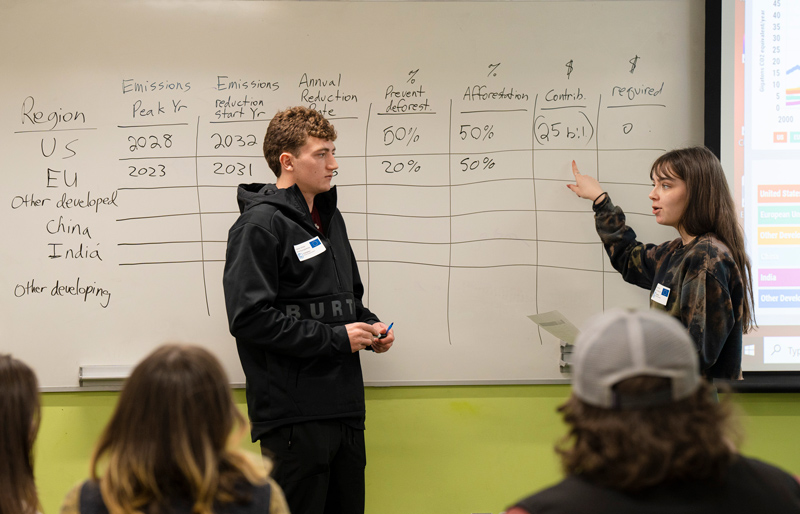

Educators can engage students in immersive simulation exercises that illustrate emissions policies and their consequences. For example, in Climate Interactive’s World Climate Simulation, students act as climate negotiators representing one of six major nations or nation blocs at a United Nations conference where the goal is to reach an agreement that keeps global average temperature increases “well below 2 degrees Celsius” above the preindustrial average.

Students carrying out a World Climate Simulation review briefing papers with information about their bloc’s economic and emissions profiles and negotiation goals before adopting any of a variety of pledges to control future emissions and deforestation. Pledges are entered into the associated C-ROADS climate simulator, which provides real-time feedback on how the pledges will affect future climate.

The simulation activity usually involves multiple rounds of negotiations among the different blocs, in which participants refine their pledges and develop a deeper understanding of the timelines and commitments necessary to achieve the climate goal and of the competing interests among countries. Surveys of more than 2,000 participants in the World Climate Simulation have shown that it effectively promotes feelings of both urgency and hope among participants, as well as an intent to learn more and a desire to act [Rooney-Varga et al., 2018]. Our own experience is that the simulations are engaging, lively sessions that result in realistic and unpredictable outcomes.

Internships and service learning opportunities can be among the most impactful experiences for students. Instructors can help by publicizing and helping students pursue such experiences. Students who work directly in city or state agency offices, organizations, or companies that do local and regional work on climate solutions, emissions reductions, and mitigation planning gain valuable connections for future employment and action. They also gain an understanding of how concrete policies can make a difference in real-world settings [Coleman et al., 2017]. Seeing how such internships have influenced students’ future career paths has been among our most rewarding mentoring experiences.

Finally, educators should encourage students to share with others what they’ve learned about the urgency of climate change and about ways to combat it. For example, students can email or write postcards to local stakeholders or decisionmakers about the need for action. We also encourage students to view themselves as “nerd nodes,” or trusted sources on science for people in their networks [Willingham, 2013], and to begin conversations with family members and others in their community about climate change.

To help in this effort, we point them to valuable science communication resources (e.g., this piece on how to talk about COVID-19) to help them think about how best to frame their message. Students have reported feeling empowered to talk with people outside of class about what they have learned and how rewarding that experience was.

From Empowerment to Action

All educators hope that their students and audiences internalize what they learn so they can apply the knowledge beyond the classroom. For those of us who educate about climate change, it is especially imperative that we motivate students to act constructively with respect to the climate crisis.

Instead of asking whether climate change is real and why it matters, many people—notably students and young people—now ask, “Is there any hope?” and “Is there anything I can do?”

The concept of hopeful alarm reflects the rapid and dramatic shift in public attitudes about climate change in recent years. Instead of asking whether climate change is real and why it matters, many people—notably students and young people—now ask, “Is there any hope?” and “Is there anything I can do?” Hopeful alarm provides a framework for answering those questions through positive, motivating messaging.

The scale of the climate challenge is vast, so the entrée to action can be overwhelming. Students benefit from exposure to specific, practical examples of actions and role models as well as from their own experiences with getting involved. By providing these examples and facilitating these experiences, we highlight clear pathways and equip those most likely to act on behalf of the climate with the tools they need to be successful.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Marlon for contributing to discussions that influenced the direction of this essay.

References

Coan, T. G., et al. (2021), Computer-assisted classification of contrarian claims about climate change, Sci. Rep., 11, 22320, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01714-4.

Coleman, K., et al. (2017), Students’ understanding of sustainability and climate change across linked service-learning courses, J. Geosci. Educ., 65, 158–167, https://doi.org/10.5408/16-168.1.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2023), Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. A Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Geneva, Switzerland, ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/.

Johnson, A. E., and K. K. Wilkinson (2020), All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis, One World, New York.

Leiserowitz, A., et al. (2022), Global warming’s six Americas, September 2021, Yale Program on Clim. Change Commun., climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/global-warmings-six-americas-september-2021/.

Mann, M. E. (2012), The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches from the Front Lines, Columbia Univ. Press, New York, https://doi.org/10.7312/mann15254.

Mann, M. E. (2021), The urgency and agency of this climate moment, Hill, 4 Feb., thehill.com/opinion/energy-environment/537171-the-urgency-and-agency-of-this-climate-moment/.

Marris, E. (2021), Inevitable planetary doom has been exaggerated, Atlantic, 1 Feb., theatlantic.com/science/archive/2021/02/other-side-catastrophe/617865/.

Marx, S. M., et al. (2007), Communication and mental processes: Experiential and analytic processing of uncertain climate information, Global Environ. Change, 17, 47–58, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.10.004.

Rooney-Varga, J. N., et al. (2018), Combining role-play with interactive simulation to motivate informed climate action: Evidence from the World Climate Simulation, PLoS ONE, 13, e0202877, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202877.

Sabherwal, A., et al. (2021), The Greta Thunberg effect: Familiarity with Greta Thunberg predicts intentions to engage in climate activism in the United States, J. Appl. Soc. Psychol., 51, 321–333, https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12737.

Willingham, E. (2013), Can nerd nodes reach registers of scientific consensus?, Forbes, 8 Feb., forbes.com/sites/emilywillingham/2013/02/08/can-nerd-nodes-reach-resistors-of-scientific-consensus/.

Author Information

Jeffrey D. Corbin ([email protected]), Union College, Schenectady, N.Y.; Meghan A. Duffy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Jacquelyn L. Gill, University of Maine, Orono; and Carly Ziter, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada