The American West, while steeped in mythology, is also a region that depends heavily on science for its long-term livability—and perhaps no one was quicker to realize that than John Wesley Powell. A Civil War veteran and an indefatigable explorer, Powell landed on the national stage in 1869, after an expedition he led became the first to navigate the Colorado River’s path through the Grand Canyon.

In the decades that followed, Powell would argue that careful, democratic management of water resources in the West must be a crucial component of its development and that a pattern of settlement and land cultivation based on the 19th century status quo would prove unsustainable.

He couldn’t have had a more unreceptive audience. Elected officials, industry titans, and even fellow scientists wanted a narrative that better supported the westward march of “progress,” narrowly defined.

Fast-forward 150 years, and Powell’s 19th century appeals are making modern headlines on the strength of their perception and foresight. Even while western states lead the nation in population and economic growth—Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, and Utah were among the top five states with the fastest growing gross domestic product between 2016 and 2017—drought conditions that have persisted for decades have left parched cities under constant threat of water emergencies.

On the Colorado River, the country’s two largest reservoirs—Lake Mead on the border between Nevada and Arizona and Lake Powell (so named for John Wesley) on the border between Arizona and Utah—are being drained faster than they can replenish. The effects of climate change are only adding to the pressure on limited water supplies.

In Powell’s account of his explorations, published in 1895 as Canyons of the Colorado, he describes the river’s waters emptying “as turbid floods into the Gulf of California.” Today, only in very wet years does the river reach the ocean. Meanwhile, communities that rely on the Colorado for water, including sprawling metropolitan areas like Phoenix, Denver, and Los Angeles, are facing the possibility of having their supply cut off or severely limited in a future that’s moving alarmingly nearer.

Unforeseen Potential

It’s tempting, then, to imagine how the West might have evolved had Powell’s vision for its development been implemented, rather than shunned, a century and a half ago.

What if Congress, undeterred by the siren song of American expansion, had listened to the call of the pragmatic?

Would L.A. be a backwater?

Would Tucson even appear on the map?

Would the Colorado still rush freely to the gulf from its headwaters in the Rocky Mountains?

Speculation about what might have been is complicated by society’s shifting priorities and values, as well as by technology. Powell, for his part, envisioned much smaller communities dispersed over the western landscape.

“One of the big things that would’ve happened if we’d listened to Powell is that we…would have responded earlier to the information about global climate change.”

“One thing that he didn’t anticipate [was] the degree to which we would accumulate western society in big, urban complexes,” says Jack Schmidt, the Janet Quinney Lawson Chair in Colorado River Studies at Utah State University and former chief of the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center.

Powell, Schmidt says, might not have imagined that these urban complexes “would have these tentacles that extended way out into the distant landscape [or] the degree to which these big urban centers would be maintained by these really long canals…these really complicated electricity transmission systems that bring in power from distant coal-fired and nuclear and hydroelectric dam facilities.”

Although Powell’s vision of small communities was largely focused on irrigated agriculture, water management, he thought, would be developed at a more local scale. This would, among other benefits, help to hedge against the uncertainties of climate variation. When, for instance, the 1922 Colorado River Compact apportioned shares of Colorado River water to seven states, it was during a particularly wet period, leading to overestimated water allocations.

“One of the big things that would’ve happened if we’d listened to Powell is that we…would have responded earlier to the information about global climate change,” says John F. Ross, author of The Promise of the Grand Canyon: John Wesley Powell’s Perilous Journey and His Vision for the American West. “He was a great proponent of America’s potential; he just wanted to do it in a way that was sensible to what was on the ground.”

When the West Was Young

The Union Army major—who was injured while fighting in the Battle of Shiloh—conquered the unpredictable 1,600-kilometer route with one arm, a small fleet of wooden rowboats, and a cobbled-together team of nine willing but inexperienced adventurers.

In 1869, as the post–Civil War United States was knitting itself back into a union, the sparsely settled expanse of states and territories that stretched between the 100th meridian and the Pacific coast was still a great unknown for many Americans. That year, Ulysses S. Grant was inaugurated as the 18th president of the United States, Wyoming became the first U.S. state or territory to grant women’s suffrage, and a spike driven at Promontory Summit in Utah connected the country’s first transcontinental railroad.

To many communities in the East and Midwest, the newly accessible West was brimming with possibility and scarcely tapped resources. John Wesley Powell, then a professor of geology at what is now Illinois State University, had identified an opportunity as he contemplated the last blank spot on the map of the continental United States: the Colorado Plateau. Today it’s an area made up of eight national parks—including Arches, Zion, and Grand Canyon—and nearly two dozen national monuments, historic sites, and recreation areas. In Utah alone, the region’s five national parks brought in 15.2 million visitors in 2017.

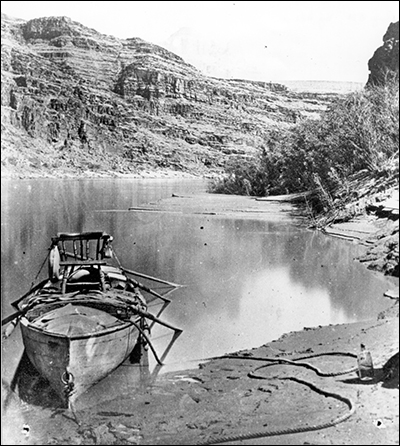

But in the late 19th century it was an altogether different story. When Powell undertook the 3-month descent of the Colorado River in the name of science, the journey was considered by some to be all but suicidal. Still, the Union Army major—who was wounded while fighting in the Battle of Shiloh—conquered the unpredictable 1,600-kilometer route with one arm, a small fleet of wooden rowboats, and a cobbled-together team of nine willing but inexperienced adventurers (all white men).

The expedition departed from Wyoming’s Green River City on 24 May 1869, with 10 months’ worth of supplies, an optimistic collection of scientific tools, and, among some of the men, hopes of finding a fortune. Four men would eventually abandon the expedition, one at the first opportunity and three others less than 2 days before the remaining team successfully emerged from the Grand Canyon. (Those three men were never seen or heard from again.)

Although Powell’s scientific ambitions for the expedition were largely scuttled by the demands of survival, the widely heralded trip would help to launch his decades-long career as a geologic surveyor, shrewd political player, and government administrator. His recommendations to Congress would be instrumental in the creation of the U.S. Geological Survey, and he would later serve a dozen years as its director while also leading the Smithsonian’s Bureau of Ethnology and helping to found the Cosmos Club and the National Geographic Society.

But it was Powell’s unswaying advocacy for land and water management in the West that would prove to be one of his most remarkable legacies.

A Watershed Idea

It was the railroad that made it possible for Powell and his team to launch the expedition from the banks of the Green River. The conveniently located station at Green River City meant that Powell could easily bring his boats and supplies by train. But the technology that benefited Powell’s plans in 1869 would also facilitate the idealistic expansion that he would ultimately spend the latter part of his career warning against.

The completion of the transcontinental railroad was especially timely for a nation in pursuit of Manifest Destiny, which disregarded the realities of climate and the native peoples who occupied the land in favor of spreading American industrialism and progress from coast to coast. Politicians, speculators, and homesteaders were eager to exploit the promise of the West’s seemingly endless resources and would be quick to deny the hard truth that lives and livelihoods depended on one all-important ingredient: water.

In his 1879 Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States, with a More Detailed Account of the Lands of Utah, with Maps, Powell foresaw the consequences of applying American optimism—and opportunism—in a part of the country where annual rainfall measured below 50 centimeters a year. He warned that there wasn’t enough water to support large-scale farming or the rapid settlement of federal lands stimulated by the Homestead Act of 1862. In addition, the costs of establishing effective irrigation systems threatened to keep control out of the hands of small farmers.

Certain conditions, Powell said, had to be met to develop the region successfully, including the identification of irrigable areas and local control of dam and irrigation projects.

It was a position Powell would refuse to abandon.

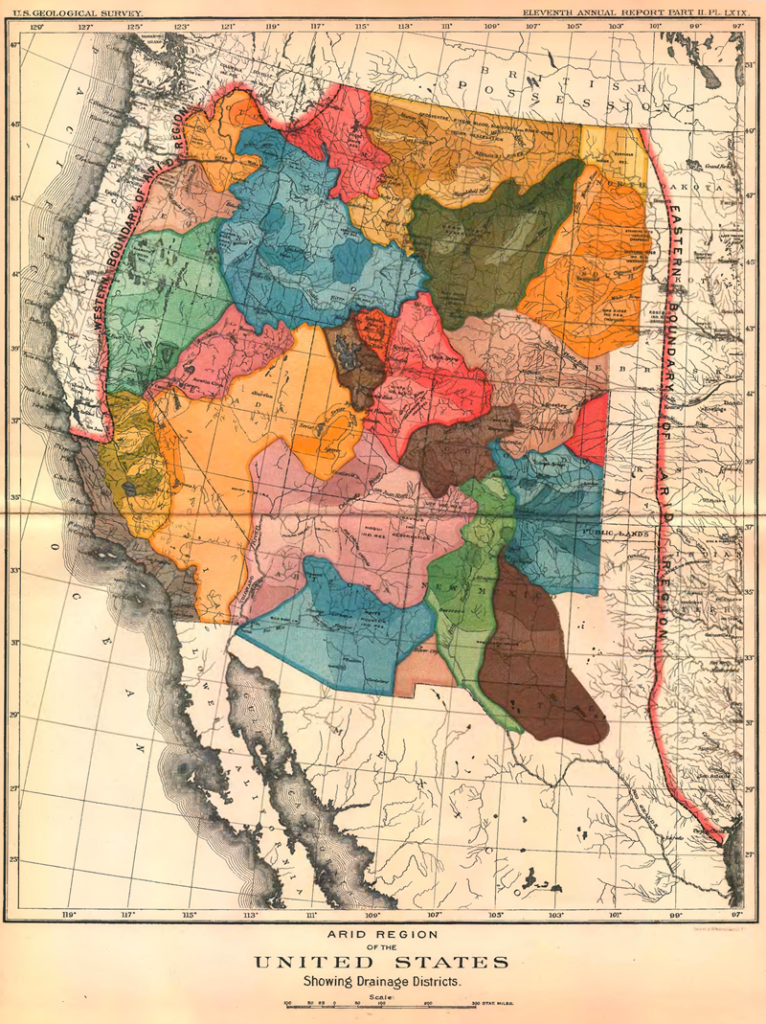

While testifying before a congressional committee in 1890, when he was head of the USGS, Powell deployed a unique visual aid: a map that divided the western states and territories into a series of drainage districts.

On first viewing, it’s a surprising example of 19th century cartography, made all the more striking with rich colors and irregular, organic-looking boundaries that contrast sharply with the boxy borders we’re familiar with today.

But the schematic didn’t hold water, so to speak, with a nation determined to grow and expand. The outlook of the nation was invested in myths that encouraged development and defied science, whereas Powell, Schmidt says, lacked the tolerance for pursuing such myths, including the widely held belief that “rain follows the plow.”

In 1902, the year Powell died, Congress passed the Reclamation Act to “reclaim” the arid region for agriculture and settlement.

“That set the stage for this really large-scale water development in the West that almost defied the functioning of the watershed from an ecological perspective,” says Sandra Postel, founder and director of the Global Water Policy Project and author of Replenish: The Virtuous Cycle of Water and Prosperity.

Today, “the river is really operated more according to needs for hydropower, flood control, irrigation, and water supply,” Postel says. “You couldn’t have cities like Las Vegas and Los Angeles and Phoenix and Tucson without this extra water.”

In the Same Boat

Powell “introduced the idea that arid cultures either stood or fell…not on the absolute amount of water, but on how equitably—politically and economically—the system divided that resource.”

Although deeply unpopular at the time, today, it’s apparent that Powell’s insistence on viewing the West’s water problem with scientific objectivity was a forward-thinking approach. Now science is taking a leading role in helping to reclaim the region for the environment while facilitating ways for a growing population to live there sustainably.

Powell believed that “science is a process of continually improving the details of our understanding of natural processes, and he would be very proud of the role of science in informing river management and protection,” says Schmidt.

According to Ross, Powell set the stage for the type of conversation we should be having about our natural resources. “He introduced the idea that arid cultures either stood or fell…not on the absolute amount of water, but on how equitably—politically and economically—the system divided that resource,” he says.

And what lessons can be taken from Powell as the West moves forward?

Says Ross, “We’re seeing this kind of bioregionalism now, where decisions are made not by the federal government but on a more local, or regional, basis—[which is] really the only way to work out these very knotty issues.”

Postel says that successful restoration often involves collaboration, such as conservationists working with farmers to find solutions to water management issues.

“If we get smarter about using and managing water, we can do better with what we’ve got than we’re currently doing,” she says.

As the challenges and accomplishments of western settlement continue to ebb and flow, Powell’s influence still lingers.

Like Postel, Schmidt believes that the key to water management in the West is in working together as a watershed community. “In a sense, that’s an idea of Powell’s that still exists today. It’s just that the community that we call the watershed includes the entire Colorado River basin. It includes every one of the seven states, all sitting around the table together.”

—Korena Di Roma Howley ([email protected]), Freelance Journalist

Citation:

Howley, K. D. R. (2019), Green and grand: John Wesley Powell and the West that wasn’t, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO124111. Published on 23 May 2019.

Text © 2019. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.