Most days last year, Lucy Jones did not show up in her office at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Pasadena, Calif., or on the serene grounds of the California Institute of Technology, where she has served as a visiting associate in the Seismological Laboratory for more than 30 years. Instead, the renowned seismologist boarded the Gold subway line and rumbled into the heart of downtown Los Angeles, where she reported to a temporary office in city hall.

Jones spent 2014 there, on loan from the USGS, working on a plan to transform LA from an “epicenter of risk” into an “epicenter of seismic preparedness, resilience, and safety,” as the city’s mayor, Eric Garcetti, put it. Together with members of Garcetti’s staff, Jones helped develop a set of recommendations that outline the steps the city should take to brace itself for an inevitable future quake. The mayor’s office approved and released the recommendations in December 2014.

These measures include retrofitting thousands of existing buildings, revamping the city’s aging and decentralized water system, and developing robust telecommunications systems that can survive a disaster. By Jones’s own account, the proposals are ambitious but absolutely necessary.

“I’m a fourth generation southern Californian,” Jones told Eos at the American Geophysical Union’s (AGU) 2014 Fall Meeting, where she spoke about her year in the mayor’s office. Her great-great-grandparents lie buried on the San Andreas Fault, out in the dry hills near Banning, and for her, this work is personal as well as professional.

“It really is about having a future to our city,” she said.

Not a Matter of If, But When

Jones specializes in statistical seismology, and she built a career around understanding the seismic hazards that threaten Southern California. As a result, she has spent a great deal of energy over the years trying to explain to policy makers and the public that it is not a matter of if the “big one” will strike, but when. As she explained in her Public Lecture at the 2013 AGU Fall Meeting, ominously titled “Imagine America Without Los Angeles,” cities like Los Angeles must be ready.

“You can never prevent earthquakes, so we have to look at human actions and what we can do to minimize consequences.”

“The community of scientists, whenever we have the opportunity, try to make the point that this is not a problem that should be ignored,” said Lisa Grant Ludwig, a geologist turned professor of public health at the University of California, Irvine, and the president of the Seismological Society of America. “You can never prevent earthquakes, so we have to look at human actions and what we can do to minimize consequences,” she said.

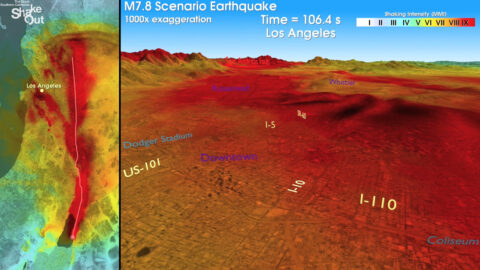

To drive this point home, Jones and 300 other scientists and engineers produced a comprehensive earthquake scenario for Southern California in 2008 called ShakeOut. It synthesized the best available scientific information regarding what the quake itself would be like (a magnitude 7.8 event is likely, although it could be larger) and what it would do to the city’s buildings, infrastructure, and economy.

The results were sobering: Jones’s team found that such a quake—unleashed by a 300-kilometer-long rupture of the San Andreas Fault—would produce damaging shaking throughout the city and offsets across the fault of up to 9 meters. Their models predicted that the disaster would kill about 1800 people; injure more than 50,000; and lead to severe building damage, widespread fires, landslides, and long-term economic losses.

If such a catastrophe were to strike the city in its current state of preparedness, the total estimated cost would exceed $210 billion. The ShakeOut report ends with a call for action by communities and their leaders: “The risks can be analyzed and described by scientists but the solutions will come from southern Californians themselves.”

From Reactive to Proactive

Despite the fact that the ShakeOut scenario garnered attention, Jones felt that people were missing one of the main points of the simulation: to highlight vulnerabilities so that they could be fixed. “People were using it for response rather than how to stop those damages,” she said. “They needed help getting from ‘here’s a picture of something awful’ to ‘this is the exact point at which you make the decision [where the effect of an earthquake] goes from bad to awful.’”

So in 2013, Jones approached the newly elected mayor, Garcetti, and told him that the city had a problem. Her visit coincided with a surge in public concern: The Los Angeles Times had just published the results of an investigation that found more than 1000 of LA’s concrete buildings could collapse in an earthquake.

During the meeting, Jones mentioned San Francisco’s efforts to brace itself for the eventuality of a severe quake in hopes that Los Angeles too could start “grappling with our issues,” she said.

San Francisco long ago established an emergency water supply for fighting fires after blazes destroyed the city in the wake of the 1906 earthquake. More recently, San Francisco’s mayor implemented a voter-backed community action plan for seismic safety that requires retrofitting unsafe buildings and devising ways to help residents and businesses survive and recover from an earthquake.

Garcetti’s office agreed that Los Angeles needed something similar, with one difference: “Their proposal was to do in one year what San Francisco did in ten, for five times as many people,” Jones recalls. So she hashed out a deal that allowed her to remain on the payroll of the USGS but spend 75% of her time in 2014 working with the city.

From the beginning, her role was very clear: Jones would provide technical assistance, but the mayor would make the final decisions about what the city should do.

Designing Resilience

“When we really look at how catastrophes happen, it’s because of collapse of an urban system. It’s not so much a million people dying; it’s a million people going, ‘I can’t live here anymore.’”

A report released on 10 December 2014, entitled “Resilience by Design,” presents the recommendations developed by Jones’s team and approved by Garcetti. The aim of the report is not just to save lives but also to build a city that can survive a disaster.

“When we really look at how catastrophes happen, it’s because of collapse of an urban system,” Jones said. “It’s not so much a million people dying; it’s a million people going, ‘I can’t live here anymore.’” As an example, she cites how New Orleans and its economy languished long after Hurricane Katrina.

So Jones’s team used the ShakeOut scenario to identify three main goals: strengthen the city’s buildings, fortify its water system, and enhance reliable telecommunications. The report lays out the mayor’s proposals for how to achieve them.

Retrofitting Buildings

To reduce building vulnerability, “Resilience by Design” calls for an aggressive approach. Although the city already dealt with the most dangerous category of buildings—brick and stone structures held together with only mortar—the report zeroes in on two other dangerous types. The first includes most concrete buildings constructed prior to 1976, when building codes did not require frames to be reinforced with ductile materials that better withstand shaking. The second is “soft-first-story” apartments—those with an open space like a garage on the ground floor, known colloquially as “dingbat” apartments.

If approved by the city council, the mayor’s proposal would require mandatory retrofits of nearly 17,500 buildings in Los Angeles over the next 5 to 30 years, depending on the building type. The recommendations also introduce a voluntary rating system to incentivize above-code building practices with tax breaks and a back-to-business plan to expedite recovery after an earthquake, among other measures.

If approved by the city council, the mayor’s proposal would require mandatory retrofits of nearly 17,500 buildings in Los Angeles over the next 5 to 30 years, depending on the building type.

The price tag associated with just the retrofits—which Jones says will likely top a billion dollars—explains why politicians have historically seen tackling earthquake problems as political suicide, said Greg Beroza, a seismologist at Stanford University who was not involved in the report.

“In any 4-year term of an elected official, an earthquake is probably not going to happen, so it’s fairly easy to kick the can down the road,” Beroza told Eos. “It’s beyond impressive to me that the mayor’s office is willing to take this on.”

Water Woes

In addition to the danger of collapsing buildings, the ShakeOut scenario highlighted the need to preserve access to water after a major temblor, not just to quench thirst but to fight the fires that will rage through the city after the shaking stops. Unfortunately, Southern California has water problems even in the best of times.

“LA gets 88% of its water from outside the region,” Jones said, “and every drop of that crosses the San Andreas Fault to get to us.”

“LA gets 88% of its water from outside the region and every drop of that crosses the San Andreas Fault to get to us.”

All told, the three major aqueducts that supply the city traverse the fault more than 30 times, and their pipes and canals will face the full brunt of fault offsets during an earthquake. Prior to ShakeOut, Jones said, “nobody in the public sphere was getting it that these fault offsets were guaranteed. We know exactly where they’re going to happen, we know exactly what’s going to break.” Her attitude, she said, was, “Let’s deal with it, guys!”

The mayor agreed. The report reflects an executive action directing the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) and other agencies that supply the city’s water to take measures to improve the chances that these vital conduits will survive expected ground motion and maintain operation during a disaster.

The report acknowledges that the LADWP is actually a step ahead—it has already hatched a plan to upgrade the Los Angeles Aqueduct, which crosses the San Andreas in a 100-year-old tunnel. The department is currently developing a proposal to install a plastic pipe that “will have a certain amount of extra material, kind of like the baggy skin on one of those dogs,” said Marty Adams, senior assistant general manager in charge of water systems for the LADWP.

The idea is that “if there’s an offset, the plastic pipe will remain intact and we’ll still have a pathway to move water,” he said.

Sourcing Sustainable Water Supplies

Although retrofits to secure a supply of water offer a short-term solution to seismic risks, Jones sees a better way. “The best defense against the breaking aqueducts is to not need them,” she said.

The report suggests that a well-developed reclaimed water system, along with methods of utilizing seawater in coastal areas, could play a major role in providing an earthquake-ravaged city with an alternative water supply to fight fires. Jones said that these are just a few of the ways that efforts to build long-term seismic resilience often overlap with efforts to increase sustainability.

LA’s San Fernando Valley Groundwater Basin, a vast reserve of nearly a trillion gallons that used to supply drinking water to close to a million residents, could also play a valuable role if its much of its current contents were not contaminated.

“Remediating the groundwater basin really ties into everything,” Adams says, from reducing dependence on outside sources to providing a place to store recycled water. “All these things all hinge on that groundwater basin being able to be fully utilized, which will only happen when we clean it up.”

The problem is that remediation will be expensive. The state recently passed a bond measure that will provide some of the funds needed to clean up the industrial waste that caused the city to abandon many of its wells in the 1980s. However, with additional contributions from polluter fines and LADWP’s customers, Adams thinks that cleanup efforts will ultimately succeed.

However, having a supply of water helps only if city pipes can transport it to fire hydrants and residents. The mayor’s executive action also calls for the LADWP to weigh the broader seismic implications of its ongoing infrastructure updates—for instance, by prioritizing work on critical backbones of the water system—and to use pipes that can withstand seismic motion whenever possible, Adams said.

Going Wireless

The population centers of Southern California last experienced major shaking on 17 January 1994, during the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake, which Jones said pales in comparison to a ShakeOut-sized event. Even so, the Northridge quake killed 57 people, left 20,000 homeless, and damaged 40,000 buildings. However, it did not disrupt cellular services—because they barely existed.

Preserving telecommunications now ranks as one of the most important aspects of any large-scale emergency response. Using other recent disasters as a guide, Jones’s team found that the main obstacle for cellular service appears to be congestion. “Hell, the system doesn’t survive rush hour!” she joked.

Expanding capacity falls beyond the purview of the mayor’s office, so instead, the team recommended pursuing a memorandum of understanding with major telecommunications companies to share bandwidth in the event of a disaster. This cooperation is not without precedent—a few companies did this on their own in New Orleans after Katrina. Upon Jones’s team’s recommendations, Garcetti’s staff have already entered into these discussions.

The second—and equally challenging—set of problems revolves around coping with the physical damage to cell towers and the electrical grid when an earthquake occurs. In an unfortunate coincidence, most cell towers currently sit atop older buildings, which will probably fare the worst in an earthquake. Even on new buildings, towers face significant threats; 2008’s magnitude 7.9 Wenchuan earthquake toppled more than 2000 towers in China, which has building codes comparable to those of the United States.

Securing power and backup power to surviving towers presents an even greater challenge. Most of LA’s towers currently have only a few hours of backup battery capacity, and increasing that power would require installing many large, dirty diesel generators. Jones said that her team quickly realized that these generators would be impractical to install, test, and maintain.

Instead, they proposed another solution: encouraging residents to use WiFi and building a universal network. “There’s a social justice proposal in the city to get city-wide WiFi to try to bring Internet access to all of our citizens,” Jones said. “If we power that with solar power, we have an amazing back-up system.”

Where Science Stops and Policy Begins

Just after the “Resilience by Design” report came out, the Los Angeles Times reported broad—albeit tentative—support among law makers and business groups for the measures, some of which still require the city council to pass ordinances before they are cemented into law. Jones attributes this uneventful reception to the team’s efforts to include the public in the process of developing the recommendations.

Over the course of the past year, Jones barnstormed the city, holding about 150 meetings with various community groups, building associations, and city departments. “I didn’t tell them they had to do this,” she said. She told them, “Here are the consequences of not doing it.”

Nonetheless, the recommendations will certainly face challenges, for example, as building managers and tenants’ rights groups determine how to distribute the burden of cost. Martha Cox-Nitikman, vice president of public policy for the Building Owners and Managers Association of Greater Los Angeles, said that her organization appreciated the efforts by Jones and the mayor to include them in the conversation. She was also pleased to see some of association’s proposals make it into the report. “But clearly the financing is something that needs to be addressed,” she added.

Logistics aside, Ludwig thinks it is the momentum behind the recommendations that matters most. “A journey consists of a bunch of steps. And this is more than a step; this is a leap forward,” she said.

Fellow seismologists gave Jones ample credit for taking that leap. Not only does she have the respect of the scientific community, Beroza said, “she’s very good at countering arguments for why we should wait to learn more and do nothing for now.” She also possesses a certain degree of celebrity with residents of Southern California. She has appeared frequently on news programs and in the papers to explain seismic events to the public, starting with the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

“She was the spokesperson in the middle of the night when everyone was scared,” said Ludwig. “She has maintained that role. People believe her and people trust her.”

Scientists Have a Valuable Role to Play

Jones is well aware of the public’s trust, and she attributes it to the fact that as a scientist, she is not perceived as representing anyone’s interests or advocating for particular choices. She said that this served her well during conversations with business groups and the public.

Scientists’ “reputation for impartial information is the most valuable thing we have,” she said. Jones firmly believes that scientists should not do policy, and she recognized that it was not her place to say what measures LA should enact to prepare for an earthquake. “It’s not a scientific question,” she said. “The scientific question is what the consequences of the different choices are.”

In the end, however, Jones was pleased with the mayor’s decisions and the report’s recommendations. “I am certain there will be an earthquake that will be a lot less awful because we did this,” Jones said.

Author Information

Julia Rosen, Freelance Writer; email: [email protected]; @ScienceJulia

Citation: Rosen, J. (2015), Los Angeles gets serious about preparing for the “Big One”, Eos, 96, doi:10.1029/2015EO024883. Published on 24 February 2015.

Text © 2015. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.