When scientists talk about the search for life in the cosmos, they often leave out a few key words: life as we know it on Earth. That usually means three things: liquid water, complex chemistry, and an energy source. It’s not a perfect definition of what’s required for life, but it’s as good a starting point as any.

But life as we know it on Earth can get pretty darn weird. Extremophiles can thrive in the most inhospitable places and make our planet seem less like a documentary and more like an episode of The X-Files—the X-philes, perhaps. We haven’t found any life beyond Earth yet, but here are five extreme environments on Earth in which life has managed to find a way and the distant worlds where we might look for their cosmic cousins.

A Martian Desert in Chile

The Atacama Desert’s rocky terrain, dried salt lake beds, and hyperarid climate make it challenging for life to gain a foothold. And yet the Atacama is home to insects, reptiles, occasional fields of flowering plants, and a few mammal species adapted to live in its extreme ecosystem.

On the basis of its looks, the Atacama has often stood in for Mars in movies and TV shows, but portions of it are actually a good scientific analogue for Mars’s soil and climate, too. Oxalate minerals, found in both places, break down through biological processes and play a role in the carbon cycle of the Atacama. Scientists think the minerals could also do the same on Mars and serve as a potential biosignature for the dry limit of life.

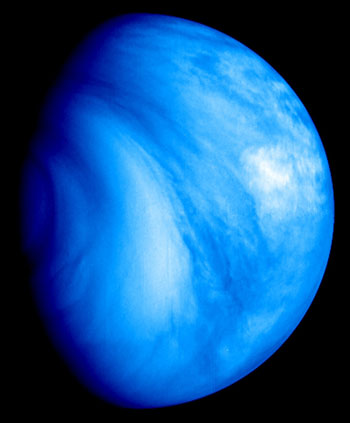

Venusian Clouds in Earth’s Atmosphere

Life on Earth doesn’t live just on the surface and in the oceans. It also floats in the clouds. Microbes including bacteria, mold spores, pollen, and algae have all been detected in various regions of Earth’s atmosphere, lofted by storms and impacts and dispersed by the wind to other locations.

The same might be true of Venus’s lower atmosphere, where conditions are much more temperate than on its surface. “Among the plausible niches for extraterrestrial life in our solar system, the clouds of Venus are among the most accessible and among the least well explored,” planetary scientist David Grinspoon said at a forum in May 2018. A study last year explored the idea that sulfur-eating, acid-resistant, and UV-absorbing bacteria similar to those found on Earth could thrive in Venus’s atmosphere.

Otherworldly Ice Blades in the Andes

Sharp blades of ice carved by sunlight cling to the sides of Andean slopes. Scientists recently discovered that these penitentes are home to microbial life that survives the intense sunlight, dry air, and icy surface. “I think it’s the first discovery of microbes on penitentes,” microbial ecologist Steve Schmidt told Eos earlier this year. “Nobody ever thought to look for them.”

Beyond Earth, penitentes have been detected on Pluto and are suspected to exist on Jupiter’s moon Europa. Studying these snow algae on Earth could give clues to how much aridity, ultraviolet radiation, and altitude life can withstand.

Titan’s Chemical Cocktail in Arctic Lakes

Titan is always near the top of the list of places to search for life beyond Earth because of its abundant surface liquid and exotic chemical composition ideal for chemotrophs to munch on. The discovery of vinyl cyanide in the moon’s atmosphere was particularly exciting for astrobiologists, as the molecules could theoretically combine with methane in Titan’s lakes to make the compounds that form cell walls.

Methane lakes on Earth are hard to find but are becoming more common in the Arctic as permafrost thaws. For the past decade, scientists have been monitoring how Arctic lakes are responding to global warming. As the permafrost melts, it releases methane gas created by biological processes and trapped in ice. Although the Arctic lakes are still composed primarily of water—something frozen rock-solid on Titan—studying their ecosystems as they become more methane rich can give insight into not only our own planet’s future but also the potential for life on Titan.

Irradiated Mold on the ISS

As far back as the Soviet space station Mir in the 1980s, scientists have known that mold is a big problem for spacecraft. Recent research has shown that some mold spores that have been found on the International Space Station (ISS) can survive X-ray exposure 200 times the dose that would kill a human. “We now know that [fungal spores] resist radiation much more than we thought they would,” microbiologist Marta Cortesão said about her team’s discovery.

This resilience might be relevant for planets orbiting stars smaller than the Sun. Many red dwarf stars have strong flares that expose nearby planets to punishing doses of X-rays and ultraviolet light. But the ISS molds hint that such stars might not be so poisonous after all—at least not to mold.

As we explore the limits of life as we know it on Earth, we begin to understand that the potential for life beyond our X-philes planet is much bigger than we had imagined—the truth is, in fact, out there.

—Kimberly M. S. Cartier (@AstroKimCartier), Staff Writer

Citation:

Cartier, K. M. S. (2019), Extreme life and where to find it, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO132337. Published on 06 September 2019.

Text © 2019. AGU. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.

Text © 2019. AGU. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.