Scientific ocean drilling (SciOD) aboard the riserless drill ship JOIDES Resolution (JR) provided unique opportunities for thousands of scientists and laid career foundations for many early-career researchers (ECRs). Hundreds of JR alumni have continued sailing throughout their careers, thriving in the fast-paced environment, conducting science at sea, and working with collaborators from all over the world.

On 30 September 2024, the contract between the National Science Foundation (NSF) and SEA1 Offshore (the private company that owns the JR) came to an end, with no plan in place for a replacement vessel.

Expedition 403 concluded the scientific work of the JR and was the second-to-last expedition of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP), “an international marine research collaboration that explores Earth’s history and dynamics using ocean-going research platforms to recover data recorded in seafloor sediments and rocks and to monitor subseafloor environments.”

The JR drilled its last cores along the western margin of the Svalbard archipelago. The selected sites sit along a major ocean gateway modulating the flow of currents between the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. Questions regarding changes in meridional overturning circulation, the climatic evolution of Northern Hemisphere ice sheets, and so much more can now be more fully addressed with 5.5 kilometers of newly acquired marine sediment cores.

Sailing as an ECR on the last expedition of the JR came with heartbreak and longing alongside the excitement. Aside from the cutting-edge science that can be conducted with the newly cored sediments, Expedition 403 was incredibly special to the three scientist-authors on board, as it was led by two women, it contained a very diverse and international group of scientists, and the majority of the U.S.-based science party were ECRs and women.

Here three ECR women share their personal accounts of sailing on the last voyage of the JR. These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Who We Are and Who We Were on Board the JR

Adriane Lam: My research lies in three main arenas: paleontology, paleoceanography, and science communication (SciComm). I use fossil marine plankton to investigate evolutionary processes through geologic time, and the chemical signatures of those same fossils help me reconstruct the behavior of surface currents across analogue warm periods. Within SciComm, my colleagues and I study how to best conduct outreach on social media platforms.

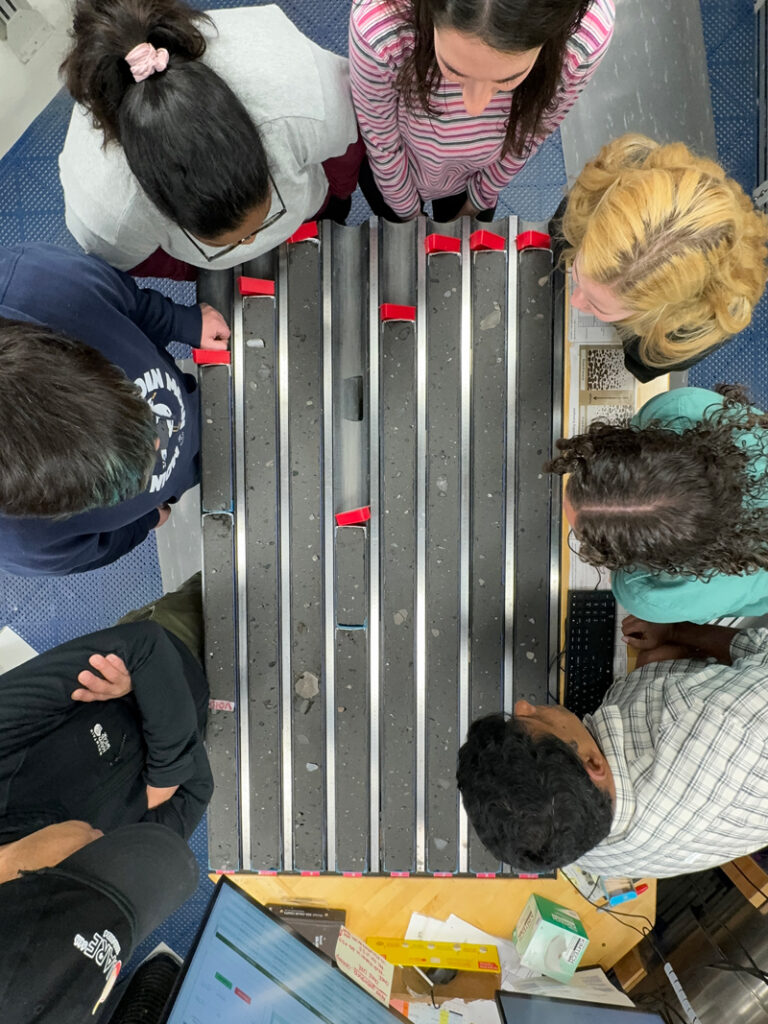

However, on Expedition 403, the three of us sailed as sedimentologists.

“After analyzing a few thousand meters of sediment, one earns the badge ‘Professional.’”

Gryphen Goss: I am not a sedimentologist—I’m more of an isotope geochemist—but as Adriane said, on Expedition 403 I sailed as a sedimentologist. This role provided me with a whole new skill set (characterizing sediment deposited over millions of years) and a new perspective on marine glacial environments.

For 2 months, each day on the JR involved 12 hours of sediment analysis, one 10-meter section at a time. Analysis included precise identification of lithology (clay, silt, silty clay, sandy mud), color (10R 4/1—know your Munsell color chart), boundary contacts (curved), clasts (how many and what size), and much more. After analyzing a few thousand meters of sediment, one earns the badge “Professional.”

Thankfully, after the day shift and midnight dinner, I could escape to the gym to hangboard or sip tea on the bow.

Nicole Greco: Although I have since transitioned my work more toward science outreach and communication, my background is in glacial sedimentology, where I used particle size as a proxy for meltwater events and bottom current speeds. Although I joined the expedition with experience describing and sampling sediment cores, the pace and number of cores far surpassed anything I had previously done.

Sailing as ECRs

Adriane: Expedition 403 was my third expedition on the JR. I first sailed on Expedition 371 to the Tasman Sea when I was a second-year Ph.D. student in 2017 and participated as a shore-based scientist on Expedition 393 in the southwest Atlantic when I was a postdoc in 2022. Sailing during three phases of my career was amazing, as I became more and more independent and confident during each expedition.

Sailing with IODP literally launched my career, as I was able to grow an international team of colleagues quickly and branched out into other research avenues. Today, I get to train my undergraduate and graduate students to conduct research on SciOD data and samples, and some have even participated on seagoing expeditions and opportunities!

Gryphen: My involvement with the IODP began in August 2021, when I started my Ph.D. My supervisor, Dr. Alan Rooney, handed me more than a hundred sediment samples collected from two sites drilled in the North Atlantic and said “get to work.” After completing my first project investigating the regolith hypothesis using radiogenic isotopes, I requested samples from the Bremen IODP core repository from the Scotia Sea in the Southern Ocean to study how ice sheets in opposing hemispheres evolved at the same time.

As someone who is very much a field scientist, I was itching to do fieldwork and was finally fortunate enough to sail for the first time on Expedition 403.

Sailing as an early-career scientist seemed somewhat counterproductive, however. On one hand, I learned the intricacies of working both on the JR and within the realm of SciOD and connected with incredibly inspirational senior scientists. But at the same time, those skills won’t be fully utilized due to the program being terminated.

Nonetheless, like many who have sailed on the JR, my experience was truly addictive. I would like to return to the same cabin—upper ’tween 4-14—and characterize sediment all day, but unlike those who have sailed in the past, my fellow 403ers and I will not get that chance.

Nicole: Although my involvement with the IODP began in 2019 at the start of my Ph.D., Expedition 403 was my first time sailing. In early 2020, I had secured funding to travel to the Oregon State University Marine and Geology Repository to collect sediment samples from Antarctic cores, an opportunity that I would not get to complete until years later due to the pandemic. This delay resulted in relying on published data and coding throughout the majority of my Ph.D., which was an amazing learning opportunity but not the field or lab work I had envisioned.

Sailing on Expedition 403 was my first opportunity for fieldwork and began less than a month after my graduation. I was driving to my grandparents’ house in south Florida when I received the news that I was invited to sail and was immediately overwhelmed with tears of excitement as I knew I was finally going to step into the shoes that some of my role models, including my graduate adviser, John Jaeger, had filled on past expeditions.

Prior to Sailing

Nicole: As excited as I was to sail, I became so nervous prior to leaving for Amsterdam (our expedition’s departure point) that I almost considered backing out. Life seemed incredibly hectic at the time, having just graduated and knowing I was moving from Florida to California just weeks after returning from the expedition.

My partner convinced me I would forever regret not taking the leap, and I’m so glad I listened to him. As soon as I arrived at the airport and met up with my friend and shipmate Lindsey Monito, I could not have been more excited to get to the JR.

Gryphen: As someone who thoroughly enjoys physically collecting data to then process and analyze, I was very excited to sail into the Arctic. The idea of working 12-hour shifts while possibly seasick, however, wore on me in the days leading up to the expedition. In the end, the feelings of worry were far from necessary. There was no worry, just blissful excitement!

Adriane: I always get super nervous before an expedition, but this was the first expedition I participated in after being diagnosed with depression and anxiety. Being on medication to help manage both conditions was a game changer for me. The over-the-top presailing anxiety was minimal, and as such, excitement about the experience was at the forefront! I also knew this expedition would be heartbreaking, being the last.

Life Aboard the Final Expedition of the JR

Gryphen: The first challenge while sailing, and sailing on the JR specifically, is adjusting to 12-hour shifts and locking in a routine. For me, the gym was truly a lifesaver after midnight dinner. Sailing in the Arctic in 24-hour sunlight made this routine much more manageable.

Getting accustomed to wearing the same two to three outfits every day for 60 days and the slight unpleasantness of the desalinated water from the shower and sink were also a bit of a challenge.

“If you ever wanted to conduct a social experiment to see 25 scientists slowly revert to childlike behavior over a 2-month period, the JR would be a great laboratory.”

Adriane: The main challenges for me while at sea are always getting to know everyone else (I’m an introvert) and fighting the urge to run to my room after shift instead of socializing.

But these weren’t a huge deal on Expedition 403, as the team was AMAZING and I quickly became close friends with a lot of the other scientists! After friendships were formed, the biggest challenge was trying to not have too much fun so I could get my work done.

Nicole: If you ever wanted to conduct a social experiment to see 25 scientists slowly revert to childlike behavior over a 2-month period, the JR would be a great laboratory. If you’ve had the pleasure of sailing on an expedition, you know how mundane your days can become. No matter how much you love looking at gray mud or small wiggles of data on a screen, it’s difficult to find ways to break up each shift.

The excitement of whales, the midnight Sun, rainbows, sea ice, a new dessert in the mess hall, having enough data to download a new playlist, or an unexpected dance party—any of these incidents was enough to make us all jump up and down like we’d never experienced them before.

The Last Cores

“Forty-plus years of scientific ocean drilling, science that shaped and molded our understanding of the Earth through time, was coming to a cold hard end at 79°N.”

Adriane: The day the JR drilled its last sediment core was honestly the worst day I’ve experienced while at sea. This was the last time the techs would work together to bring a core on deck, the last time the roughnecks would work the drill string, the last time the driller would be in the doghouse.

I outlined my feelings during the last day of coring in a blog entry.

Gryphen: As the final sections of cores were brought aboard the JR, the overall atmosphere on the ship drastically shifted. Reality hit us like a drifting iceberg and the realization that 40+ years of scientific ocean drilling, science that shaped and molded our understanding of the Earth through time, was coming to a cold, hard end at 79°N.

What I found most unexpected was the emotions felt not just by the scientists but by the crew. I was so unaware of the community and relationships that came with being on the JR. Crew members that spent 6 months of every year together aboard the JR, truly a tight-knit family, were now being pulled apart by the expiration of a long-standing contract.

Nicole: There were only two times I cried while on the JR: when I was seasick in the North Sea and thought I might not survive the transit and watching the marine technicians hug after carrying in the final core to the onboard lab. Although it was impossible for the scientists to understand the emotions of the techs and crew—we were only present for a fraction of the time that they spent on board—the day was somber for everyone involved, and it felt like one big family mourning the loss of their home.

What the JOIDES Resolution and SciOD Mean to Us

Gryphen: The mission of the IODP itself—the decades of sheer determination required to explore the world’s oceans every month of every year, to collect kilometers of sediment simply to aid in our understanding of the Earth system—is in itself incredibly motivating.

The program has provided past and future generations with unlimited research potential through repositories filled to the brim with samples that can be delivered to your door. The IODP has made a once-expensive and relatively inaccessible sample collection accessible to any scientist from anywhere.

Nicole: I’ll never forget the day I received the invitation to sail on Expedition 403. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

As a glacial sedimentologist, I rely on marine sediment cores as the primary source for reconstructing glacial cyclicity and past climate in polar regions. Collecting new cores is crucial because legacy sediment cores from previous Arctic expeditions contain little to no material spanning the most important climatic periods (warm periods that are analogues to today’s warming scenarios) due to destructive analytical methods and/or degradation with age.

Past ice sheets and the climatic conditions under which they existed can provide a vast amount of information that can be used to make predictions about the future of icy regions under a warming climate. Additionally, due to the danger and remoteness of glacial regions, it is difficult and incredibly expensive to collect near-ice measurements that can tell us about the current stability of ice sheets.

Professional and scientific opportunities provided by the JR will be missed; there are many regions around the globe that have yet to be explored and have the potential to hold key information on climate transitions and glacial changes throughout time, emphasizing the need for scientific ocean drilling to continue.

Adriane: Scientific ocean drilling meant, and still means, everything to my career. I mourn the loss of the IODP for the next generations of ocean scientists, who will never get the opportunity to sail on such an amazing ship.

It is mind-blowing that the United States, which has classified climate change as a national security threat, pulled funding from the single program that has obtained data that are integral for understanding how Earth systems processes can change and operate under conditions of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide. These data can help identify regions that will be most affected by climate change in the future. The decision to not renew the contract between NSF and SEA1 Offshore is the most disheartening and shortsighted decision made by any U.S. funding agency.

The loss of the program is a huge loss for the United States, not just the science community.

Author Information

Adriane Lam ([email protected]), Binghamton University, Binghamton, N.Y.; also at Time Scavengers; Gryphen Goss, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.; and Nicole Greco, Arctic Data Center and Learning Hub, National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, University of California, Santa Barbara