Source: Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets

Earth and Venus are “sister worlds,” sharing a similar size, mass, and bulk composition. You wouldn’t want to visit modern-day Venus, though, with its atmosphere of carbon dioxide and nitrogen and surface temperatures hovering around 450°C. But our neighbor probably wasn’t always so inhospitable.

Deciphering what early Venus looked like isn’t easy—in part because the planet’s surface is relatively young, just 300–700 million years old—but indications from the Pioneer Venus mission suggest that its atmosphere once contained more water than it does today. Venus also might have hosted liquid water at its surface, as well as plate tectonics and a stable, temperate climate; some studies even indicate that Venus’s climate may have been more stable than early Earth’s, avoiding Earth’s icy snowball periods.

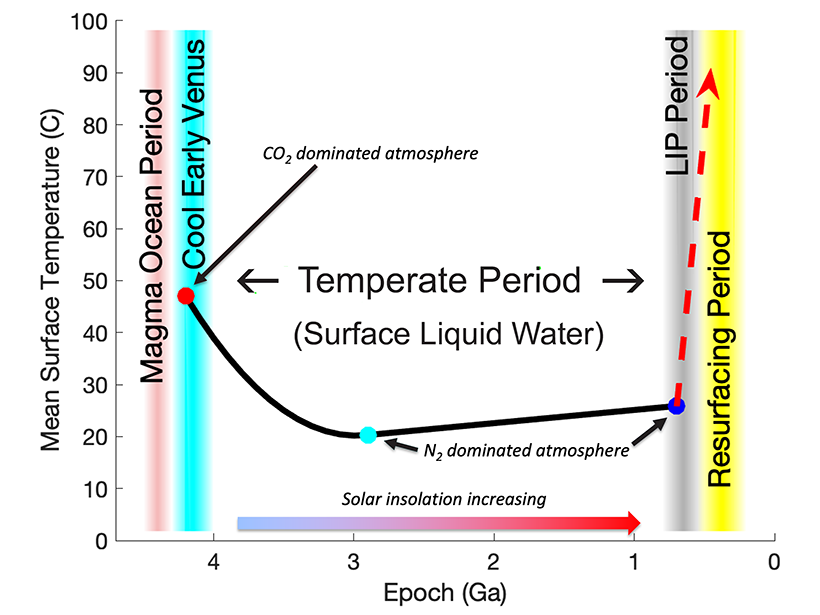

Theories abound about what led to Venus’s drastic transformation: A gradually warming Sun may have left the planet hot and desiccated after a short period of habitability, or a very early magma ocean and an atmosphere of carbon dioxide and steam could have given way to the planet’s current state nearly 4 billion years ago.

In a new study, though, Way and Del Genio provide evidence that a shallow water ocean and habitable conditions may have persisted on Venus for as long as 3 billion years, until volcanic large igneous provinces (LIPs) emerged simultaneously and ended the planet’s temperate period.

The team ran several simulations of Venus’s history using NASA’s ROCKE-3D (Resolving Orbital and Climate Keys of Earth and Extraterrestrial Environments with Dynamics) general circulation model to examine how variations in the planet’s rotation rate and surface water levels might have influenced its early climate. Assuming that Venus’s early atmosphere, like early Earth’s, was carbon rich and cool and that its rotation rate was slow, the team found that Venus’s climate could have been stable for most of the planet’s more than 4-billion-year history—a strike against the gradually warming Sun theory.

The authors believe that simultaneous eruptions of LIPs over the past few hundreds of millions of years could have led to a runaway greenhouse effect by releasing large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. The resultant drying of the planet’s surface could have driven it into a new interior-surface dynamics regime, with newly exposed basalts—evident on Venus today—acting as an efficient oxygen sink.

In Earth’s past, LIPs have emerged sequentially in a random stochastic process, rather than simultaneously, which the authors note is “fortuitous for life as we know it today.” But not enough is known about Venus’s interior to speculate whether an uninhabitable end state is the inevitable product of internal processes on Venus-like planets or even on Earth for that matter. Researchers need more observations from Venus’s surface to better constrain its early history and further challenge the magma ocean theory.

Ultimately, a better understanding of Venus’s history will provide insights into both terrestrial processes and those of exoplanets, including whether the window of habitability is wider than currently thought. (Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JE006276, 2020)

—Kate Wheeling, Science Writer

Citation:

Wheeling, K. (2020), How long was Venus habitable?, Eos, 101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO142936. Published on 08 May 2020.

Text © 2020. AGU. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.