Source: Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets

Like Earth, Mars is surrounded by an ionosphere—the part of its upper atmosphere where radiation from the Sun knocks electrons off of atoms and molecules, creating charged particles. The Martian ionosphere is complex and continuously changes over the course of the day, but its role in atmospheric dynamics and radio communication signals means understanding it is key for Mars exploration.

One way to study the Martian ionosphere is with radio occultation, in which a spacecraft orbiting Mars sends a radio signal to a receiver on Earth. When it skims across the Martian ionosphere, the signal bends slightly. Researchers can measure this refraction to learn about Martian ionospheric properties such as electron density and temperature. However, the relative positions of Mars, Earth, and the Sun mean conventional radio occultation cannot measure the middle of the Martian day.

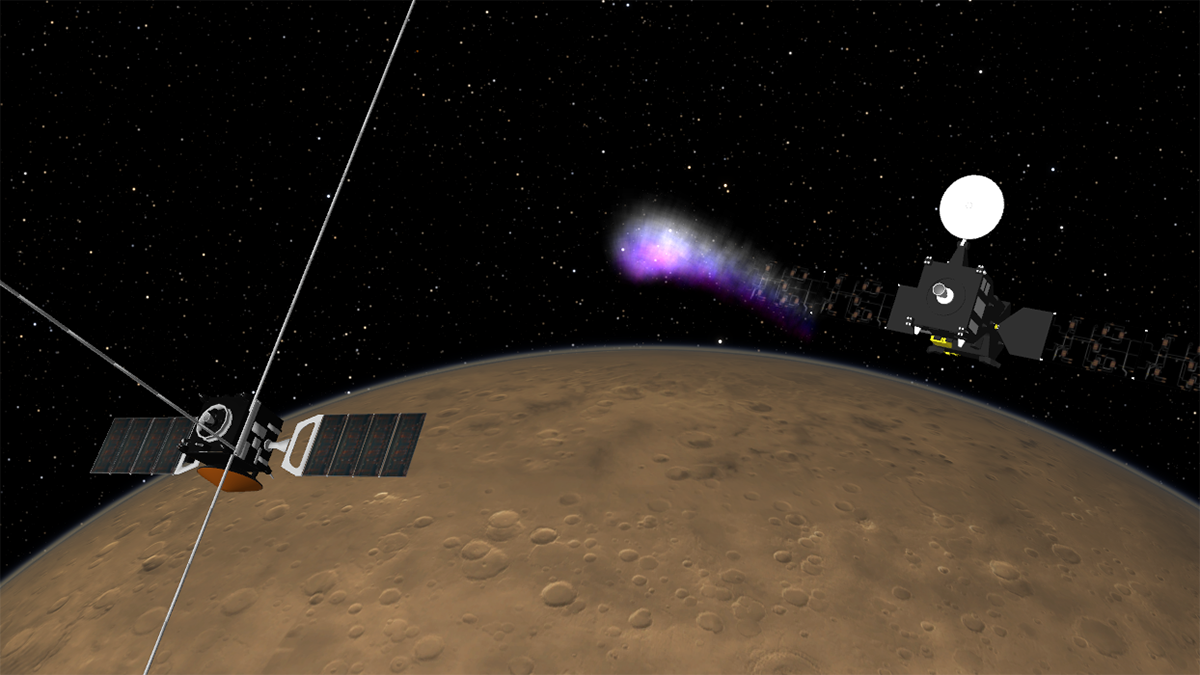

Now, Parrott et al. deepen our understanding of the Martian ionosphere using an approach called mutual radio occultation, in which the radio signal is sent not from an orbiter to Earth but between two Mars orbiters. As one orbiter rises or sets behind Mars from the other’s perspective, the signal passes through the ionosphere and refracts according to the ionosphere’s properties.

The researchers analyzed 71 mutual radio occultation measurements between two European Space Agency satellites orbiting Mars: Mars Express and the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter. Thirty-five of these measurements were taken closer to midday than was ever previously achievable, in effect allowing scientists to see a new part of the Martian ionosphere.

The new data enabled the research team to calculate how the ionosphere’s electron density changes throughout the day. They were also able to learn more about how the altitudes of the upper and lower layers of the ionosphere—called M2 and M1, respectively—vary daily. The new data suggest that the peak electron density of the M2 layer changes less dramatically during the day than has been suggested by prior research. The data also show that the M1 does, indeed, still exist during the midday, contradicting previous assumptions.

The researchers also used the new data to calculate ionospheric temperatures. They found that instead of being hottest at midday, temperatures in the ionosphere rise as the Sun reaches Martian sunset. Simulations using a Mars climate model suggest that it is likely winds transporting air, rather than the Sun’s direct heat, that control these temperature dynamics. (Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JE008854, 2025)

—Sarah Stanley, Science Writer