Dinosaurs’ eating habits and, later, their extinction may have altered the course of rivers in ancient North America, according to a new paper published in Communications Earth and Environment.

“Ecosystem engineer” is the term ecologists use for a species that significantly alters its environment. Beavers and their wetland-supporting dams provide a common example. A new look at the stark changes in rock formations dated to just after the dinosaurs went extinct suggests that they, too, could have been ecosystem engineers.

The research team suggests dinosaurs once cut down enough vegetation (through consuming, trampling, or uprooting) to create wide floodplains. After an asteroid wiped out dinosaurs, along with three quarters of life on Earth, forests emerged, constraining rivers to narrower, meandering paths.

“The only thing that fit all the evidence we had was that it’s actually the removal of dinosaurs that [changed rivers],” said Luke Weaver, a paleontologist at the University of Michigan’s Museum of Paleontology and lead author of the new study.

The argument upsets a long-held hypothesis that ancient North America was a wet, frequently flooded place in the few million years following dinosaurs’ disappearance.

An Ancient Asteroid Hits

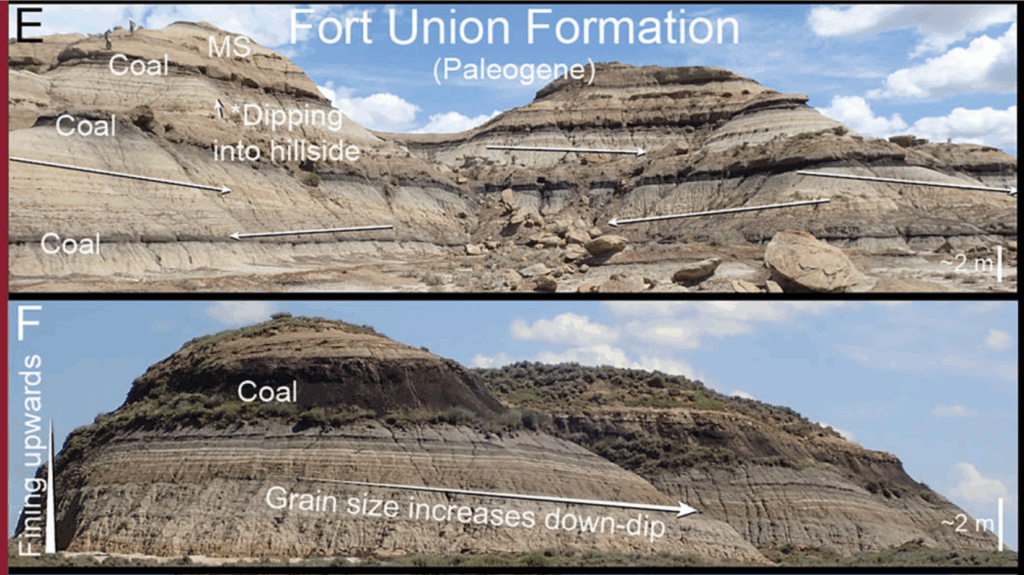

The North American geologic record shows a stark contrast, called a facies shift, between sedimentary rocks of the Late Cretaceous (just before dinosaurs’ extinction) and those created in the early Paleogene (just after dinosaurs’ extinction). For example, a Late Cretaceous formation in the present-day Great Plains, called the Hell Creek Formation, is composed of dark, gray-green mudstone. The early Paleogene rock directly above it, called the Fort Union Formation, looks much different: It’s marked by various deposits of coal and brightly colored layers described as pajama stripes.

Between these dinosaur and postdinosaur periods, scientists have found a layer of rock with elevated amounts of iridium, an element rare on Earth but common on asteroids. This layer, called the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, or KPB, is thought to have been created by the impact of the asteroid that led to the extinction of most dinosaurs.

“Most people have argued that it’s a coincidence.”

However, it’s not widely accepted by scientists that the Hell Creek–Fort Union shift and the KPB are actually related. “Most people have argued that it’s a coincidence,” Weaver said.

To further examine whether the KPB was linked to the facies shifts, Weaver and his colleagues examined five locations with facies shifts in the western United States that they thought might show the iridium anomaly. They found it in all five spots.

“Sure enough, they’re following the same trend,” Weaver said. “It’s a phenomenon that is true across the entire region.” He and the research team take the iridium results as evidence that the change in geology between the Late Cretaceous and early Paleogene formations is not simply a coincidence but related to the catastrophic asteroid impact 66 million years ago.

Ponds or Not?

Yet another mystery lurks in these rock formations. Paleontologists generally agree that the Late Cretaceous sediments of the Hell Creek Formation suggest an environment with waterlogged soils and small river deposits: a floodplain with poorly constrained river flow.

But what happened to create the features found in the early Paleocene Fort Union Formation, after the dinosaurs went extinct, is less settled. Previous research interpreted the formation’s pajama-striped pattern as variegated beds—rock features that are horizontal, uniformly fine grained, laminated (composed of very thin layers of sediment), and extensive (sometimes stretching for kilometers).

These variegated beds were likely formed by ponds, said David Fastovsky, a sedimentary geologist and paleontologist emeritus at the University of Rhode Island. Fastovsky was the first to interpret how the pajama-striped features may have formed.

His interpretation aligns with what others have called the “wet Paleogene” hypothesis—the idea that the early Paleogene was characterized by a high water table, possibly due to sea level rise.

“The obvious evidence for major flooding at that time” cannot be ignored.

Weaver and his colleagues offer a different explanation. “There are a lot of reasons why we didn’t think that was a legitimate interpretation,” Weaver said.

Instead, the research team thinks waterways in the early Paleogene were much more structured and that it’s more likely the pajama-striped beds are point bar deposits—accumulations of sediment that occur in the bends of constrained, meandering rivers. The deposits are tilted, and the sediments’ grain size increases nearer the bottom of the tilt, the paper states.

“All of those features combined are things that are very indicative of point bar deposits,” Weaver said.

Fastovsky disagrees. While point bar deposits certainly exist in the Fort Union Formation, he said the pajama-striped formations are definitively not examples of them. He thinks it’s likely that the research team misinterpreted what they called “variegated beds” in the formation.

“We’re not talking about the same rocks,” he said.

For example, some images of the Paleogene beds presented in the paper show an obvious dip, indicating to Fastovsky that the team wasn’t looking at the actual variegated beds in the Fort Union Formation. “They correctly identified what they saw, but what they saw was not, as they suggested, what we have been calling ‘variegated beds,’” Fastovsky wrote in an email.

Weaver said it’s unlikely his team analyzed the incorrect beds. “Everywhere that we see those thin beds, those sandstones and mudstones that [Fastovsky] interpreted as pond deposits, we found them to have some degree of depositional dip,” he said, adding that his research team visited nearly every spot where Fastovsky did his work.

“The obvious evidence for major flooding at that time” cannot be ignored regardless of the interpretations, Fastovsky said. Despite the disagreement, he said it’s still possible that dinosaurs altered the landscape and the way rivers flowed.

Ecosystem Engineers

The study’s authors argue that together, their findings of additional iridium anomalies and their new interpretation of the Fort Union Formation suggest that herds of Cretaceous herbivorous dinosaurs (like triceratops) could have been ecosystem engineers, drastically changing the landscape in which they lived.

Scientists know from research on modern ecosystems that large, terrestrial animals influence the type and amount of vegetation that grows on a landscape. For example, bison may influence nutrient cycling and grassland growth in the Great Plains, and African elephants routinely destroy trees and sediment in search of food.

In the new study, the authors write that large, herbivorous dinosaurs of the Late Cretaceous were likely no different. They consumed large amounts of vegetation, keeping the landscape free of dense forest and allowing water to flow across wide, open plains.

“Without a doubt, these animals had some impact on their environment—you’re talking about many, multi-ton species that were abundant on the landscape.”

Paleobotany studies have shown that after the asteroid hit, plant communities changed drastically, too: Late Cretaceous forests were more open, while early Paleogene forests had closed canopies and denser growth.

There’s simply not enough data, however, to definitively answer the question of whether the dinosaurs’ disappearance caused the change in vegetation, said Jordan Mallon, a paleobiologist and dinosaur ecologist at the Canadian Museum of Nature who was not involved in the new study.

“Without a doubt, these animals had some impact on their environment—you’re talking about many, multi-ton species that were abundant on the landscape,” Mallon said. However, scientists have little information about what that specific impact may have been.

There’s little evidence available, for example, about the particular eating habits of the large Cretaceous herbivores seen in the fossil record, such as what species of plants they ate or in what quantities.

“We really don’t know exactly how dinosaurs modified their landscapes,” he said.

—Grace van Deelen (@gvd.bsky.social), Staff Writer