The Next Scientific Challenges

• The Road Ahead…

• A Geodata Fabric for the 21st Century

• No Place to Flee

• Machine Fault

• Our Greatest Challenges Require Science, Not Silence

• Communities Thrive with Thriving Earth

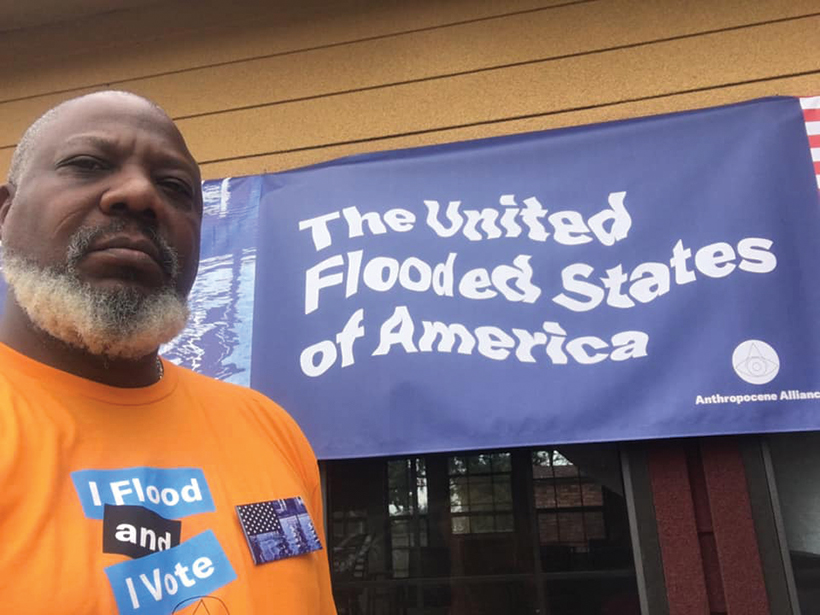

When Hurricane Harvey hit Port Arthur, Texas, with a record-shattering 1.5 meters of rainfall in August 2017, the home of local activist and community organizer Hilton Kelley was among thousands that flooded in the coastal city. “I had 3 feet of water in my house,” Kelley said.

Floodwaters ultimately affected about 80% of the city’s homes. “This is something that is still impacting our community two years later,” Kelley said. “It’s hitting everybody directly.”

Kelley, founder and director of Community In-Power and Development Association Inc., has long advocated for environmental justice in Port Arthur’s lower income and predominantly African American neighborhoods, where proximity to oil refineries has led to higher than average cancer mortality rates within the state of Texas.

When Harvey brought flooding that displaced neighborhood residents, Kelley was quick to speak on their behalf. His efforts soon caught the attention of Harriet Festing, cofounder of the grassroots advocacy nonprofit Anthropocene Alliance. Festing was interested in assembling a network of flood survivors and was just getting started with the project that would become Higher Ground, which provides community groups with the tools they need to take action against flooding.

“My experience with Harriet is, number one, she’s very determined,” Kelley said. “She was very adamant about doing something in a big way.”

Festing worked with Kelley to establish what Port Arthur flood survivors needed most—from clothing to relocation out of flood-prone areas—and offered to direct him to resources.

One of those resources was AGU’s Thriving Earth Exchange.

“The partnership has been transformational for the whole organization,” said Festing, a former British government civil servant who has spent 25 years managing climate change programs. “It’s had a massive influence on our program.”

Community First

Five years ago, as AGU geared up to celebrate its Centennial in 2019, organization leaders wanted to find a way to both recognize the achievements of the past century and help set a foundation for the next 100 years. Thriving Earth Exchange grew out of that goal, and this fall the initiative celebrated a fitting milestone: 100 projects undertaken around the United States and the world.

The program brings community leaders and scientists together to solve, at a local level, some of the most important challenges facing regional populations in the 21st century, including those related to climate change, natural resources, and pollution. Many of the communities Thriving Earth Exchange works with are historically underrepresented and underserved, and the partnership facilitates action on priorities set by those communities.

Some, like Port Arthur, seek scientific support in the form of maps or studies—tools that can empower communities making a case for policy change. Others need assistance interpreting and communicating complex data or navigating unfamiliar technical terrain and infrastructure challenges. Some want help collecting and interpreting data about the places where they live, work, and play.

“We want to make sure that every community that wants to has the ability to frame and investigate their scientific questions.”

Residents of Evanston, Ill., who have long grappled with the damaging effects of a waste transfer station, sought scientific expertise for an environmental monitoring study. The city’s partnership with an environmental engineer through Thriving Earth Exchange resulted in a sampling plan and equipment recommendations based on contaminant levels identified during the project.

In Flint, Mich.—which has struggled economically for decades and in 2014 began a protracted battle against lead-contaminated drinking water—Thriving Earth Exchange paired Michigan-based landscape architects with a community organization that wished to design and build the city’s first green roof. Community pride and empowerment are at the core of the project, which will provide an energy-efficient solution for a space that serves at-risk youth.

The common thread across all of Thriving Earth Exchange’s projects? Science.

“Science is a kind of knowledge, a kind of power,” said Raj Pandya, director of Thriving Earth Exchange. “We want to make sure that every community that wants to has the ability to frame and investigate their scientific questions.”

Community science, the concept at the heart of Thriving Earth Exchange, “always starts with community priorities,” Pandya said. “[It’s about] sitting down with communities, understanding what their priorities are, what they want to accomplish…then designing science projects that help them achieve those aspirations. It’s a very collaborative, cogenerative process that really respects community agency and community knowledge.”

Working in direct partnership with volunteer scientists drawn from Thriving Earth Exchange’s extensive network, civic leaders and activists establish shared values and goals and implement a plan that will produce concrete results over 6–18 months. In some cases, a project will kick-start additional conversations, producing the ripple effect of community science.

A Flood of Possibilities

Festing’s Higher Ground is one example of how many lives the ripple effect can touch. Today the organization is the largest flood survivor network in the country, working with 50 advocacy groups in 22 states and helping to catalyze the United Flooded States of America campaign and 15 projects in collaboration with Thriving Earth Exchange.

According to Sarah Wilkins, a Thriving Earth Exchange project manager, the initiative’s collaboration with Festing is unique. “Harriet is able to connect us to people who are dealing with these things on the ground and who are incredibly fired up and ready to address the issue,” she said.

Festing “made every difference,” said Susan Liley, cofounder of Citizens’ Committee for Flood Relief (CCFR) in De Soto, Mo., where frequent flash flooding of the Joachim Creek has claimed three lives since 2003 and has destroyed and continues to endanger homes and businesses. Festing connected Liley with Thriving Earth Exchange, and today CCFR works with a team of four U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and Saint Louis University scientists.

Since the committee’s inception, action by Liley and cofounder Paula Arbuthnot has set in motion the development of a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers floodplain management plan, the installation of a USGS flood alarm system, and zoning analysis by the city and county.

“The niche that needed to be filled was one of education,” said Robert Jacobson, a USGS research hydrologist at the Columbia Environmental Research Center who was matched with CCFR through Thriving Earth Exchange. As part of the project, Jacobson and his team interpret and communicate technical and scientific data for CCFR and the wider community.

“Ultimately, our goal is to provide the citizens of De Soto with a better understanding of their risks,” he said. They do this in part by attending committee meetings, answering questions, addressing concerns, and giving presentations on topics like climate change.

“They lead us through [the project] every step of the way,” Liley said.

For Jacobson, working with Thriving Earth Exchange has provided an opportunity to expand his work beyond research and see from another perspective the issues his team is tackling. “It’s useful for us to just put on another set of lenses, to get a sense of where that connection is between science and society,” he said. “I think [there are] thousands of other small towns—and other communities—that would benefit from this sort of interaction.

Liley agreed. Through Facebook, she connects with other flood survivor groups, offering them encouragement and gathering ideas for approaches that can be applied in De Soto. “It’s not just about the coastal areas,” she said. “It’s about little towns like ours that flash flood from a little, tiny creek. It’s about all of America.

The Total Difference

Although Thriving Earth Exchange began as a national program, it has expanded to include international projects in Africa, Central Asia, Central and South America, and the Caribbean, and the hope is to have an ever growing footprint around the world.

“There’s nothing like Thriving Earth Exchange. It’s extremely rigorous, and frankly, that makes the total difference. It wouldn’t work if it didn’t have that rigor.”

As global issues like climate change increase the need for resilience and sustainable solutions, cities like Port Arthur and De Soto—and organizations like Higher Ground—will be joined by others driven to take action for the long-term benefit of their communities. And the goal of Thriving Earth Exchange is to be part of their stories.

“We really feel that science can be a useful contributor to local challenges, and the best way to do that is not to tell people what the challenges are but to let the challenges emerge from their own experience and find ways to contribute,” Pandya said.

Festing, who stays involved with the projects she helps facilitate, pointed to CCFR’s accomplishments in De Soto as an ideal example of what can be achieved with scientific support. “There’s nothing like Thriving Earth Exchange,” she said. “It’s extremely rigorous, and frankly, that makes the total difference. It wouldn’t work if it didn’t have that rigor.”

How to Get Involved

If you have an idea for a Thriving Earth Exchange project in your community, apply here. Scientists who would like to volunteer with the Thriving Earth Exchange can apply for an existing project or sign up to be matched with future opportunities here. If you would like to be a community science fellow and help guide a project, sign up here.

—Korena Di Roma Howley ([email protected]), Freelance Journalist

Citation:

Howley, K. D. R. (2019), Communities thrive with Thriving Earth, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO136388. Published on 25 November 2019.

Text © 2019. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.