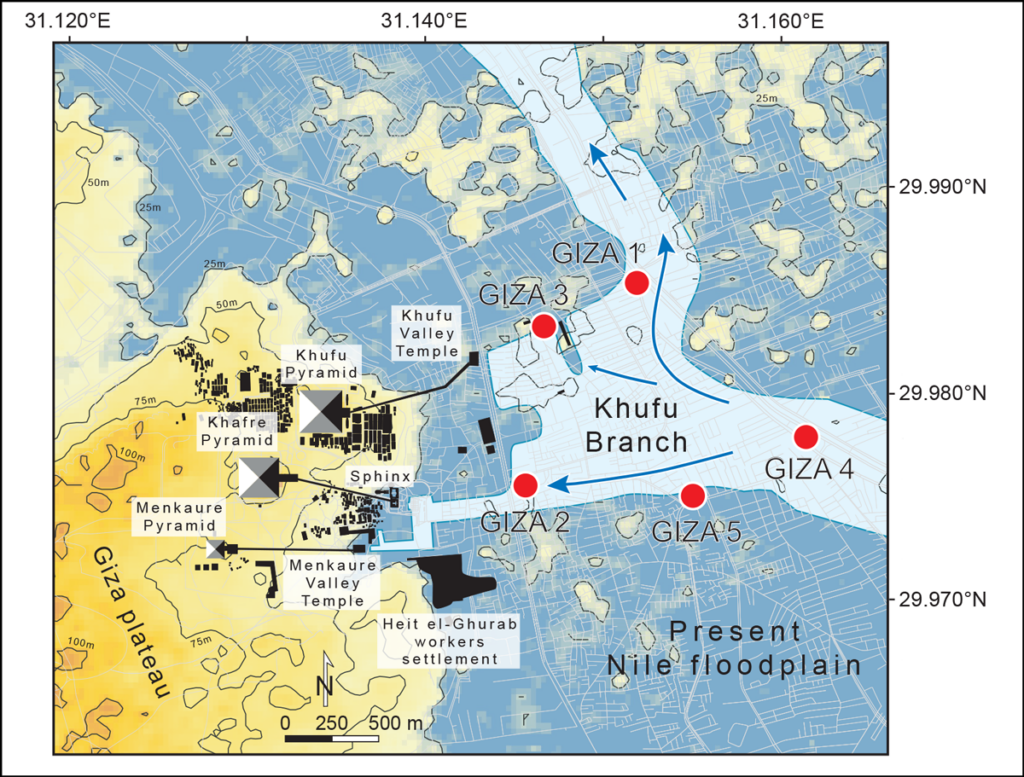

Perhaps the most well-known wonder of the ancient world, the pyramid of Khufu was built about 7 kilometers west of the present-day Nile River, in what is now the city of Giza, Egypt. Giza lies within the Nile River delta, a 26,000-square-kilometer expanse of fertile soil. The complex is “on the frontier between the desert and the floodplain,” said Hader Sheisha, a physical geographer at Aix-Marseille University, France.

The distance between the Nile and the Giza pyramid complex has long led researchers to question how massive stone blocks were transported to the building site.

New research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, claims that a now abandoned channel of the Nile—termed the Khufu branch—once flowed freely through Giza. Ancient engineers and workers, authors say, took advantage of the waterway to easily move materials from quarries downstream to the deltaic necropolis.

Drilling Through History

Sheisha, a doctoral student and lead author of the new paper, and her colleagues drilled nearly 9 meters beneath Giza’s streets, open areas, and gardens. They collected sediment cores documenting 8,000 years of history.

Skeptical residents and onlookers assumed the researchers were looking for riches, Sheisha said. People would come to ask, “What are you looking for?” she remembered. The group was looking for a different sort of treasure—microscopic grains of pollen deposited over the millennia.

The plants that covered the ancient Nile landscape and the pollens they brushed off were not unlike those of today. Papyrus grew on stream banks, and ferns and grasses took root farther from water.

The Giza sediment cores revealed a layered history of shifting pollen species. This history indicated that the plants growing at these locations, and thus the wetness of the sediments, changed over time. The waxing and waning of the river level in the Khufu channel ultimately ended with a mostly dry streambed.

At the time the Giza pyramid complex was built—between 2670 and 2500 BCE—the channel was about 40% as high as during the African Humid Period, a peak wet period more than 1,000 years prior. This earlier period saw relatively soggy conditions throughout northern Africa and a mostly green Sahara desert. Though the core data do not constrain the Khufu branch’s exact channel depth, they indicate there was plenty of water for small boats to navigate to Giza, according to the researchers.

Other scientists are more hesitant to pin down the exact river level at this time. “This is an interesting approach, but [the study] is speculative,” said Mark Macklin, a geomorphologist at the University of Lincoln. He cited limited constraints on the dates in the cores as a reason to not overinterpret the results. “It would have been good to actually relate it to the sediment and geological based literature which exists in this region.”

If accurate, the finding would support archaeological evidence that the Giza pyramid complex housed a harbor that builders used to bring supplies by water, rather than having to transport 2.3-ton stone blocks across the desert. From the Khufu branch, builders would have been able to dredge a short channel right up to the base of the site itself.

The sediment cores also hint at why Giza may have been chosen by Egypt’s rulers, who lived 16 kilometers away in Memphis, as the site of their tombs. The Khufu branch’s stable water levels made Giza an attractive site for monumental construction projects, Sheisha explained.

“It was an important factor for the builders and engineers in choosing this place because it seems to have been very suited for their needs,” agreed Eva Lange-Athinodorou, an Egyptologist at the University of Würzburg who was not involved in the new research.

Geography Is Destiny

For a thousand years, the Nile River flooded its surrounding plains with a tonic of nutrients that fed the industrious civilizations dotting its banks. In the otherwise arid landscape of the eastern Sahara desert, communities relied on the predictability of the annual flood levels to sustain agriculture and move goods.

The fluctuating Nile documented by the new sediment research corresponded to a fluctuating social and political system in Old Kingdom Egypt, although many Egyptologists are hesitant to draw conclusions. Following the Fourth Dynasty, pharaohs started building their pyramids away from Giza. (Khufu was the second pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty and commissioned the largest of Giza’s three pyramids.) The subsequent period saw pharaohs lose much of their power to local governors. Archaeological records show that instability in Egypt was accompanied by widespread famine and conflict across northeast Africa and Mesopotamia and as far east as the Indus Valley.

“It is fascinating to see that…environmental change was a deciding factor [in pyramid building].”

The shift in funerary construction away from Giza was an odd move in a culture that emphasized continuous familial succession of leaders, Lange-Athinodorou said. Previous explanations for the shift included royal feuds or changes in religious beliefs. “The timeline is a bit fuzzy,” she said, but the new core data show that around the end of the Fourth Dynasty, water levels in the Khufu branch dropped, potentially making construction at Giza more difficult.

“It is fascinating to see that…environmental change was a deciding factor [in pyramid building],” she said.

—Jennifer Schmidt (@DrJenGEO), Science Writer

This news article is included in our ENGAGE resource for educators seeking science news for their classroom lessons. Browse all ENGAGE articles, and share with your fellow educators how you integrated the article into an activity in the comments section below.