Earth’s beautiful, neon-colored aurorae occur when charged particles from the sun (the solar wind) collide with the planet’s outer atmosphere, called the ionosphere. While this bombardment could spell trouble for Earth-dwellers, the Earth’s magnetic field lassos the particles and channels them up above the poles. Brightly luminescent, the aurorae manifest as clouds and ribbons in the sky.

“For the first time, we have witnessed how electrons are accelerated in Mercury’s magnetosphere and precipitated onto the planet’s surface.”

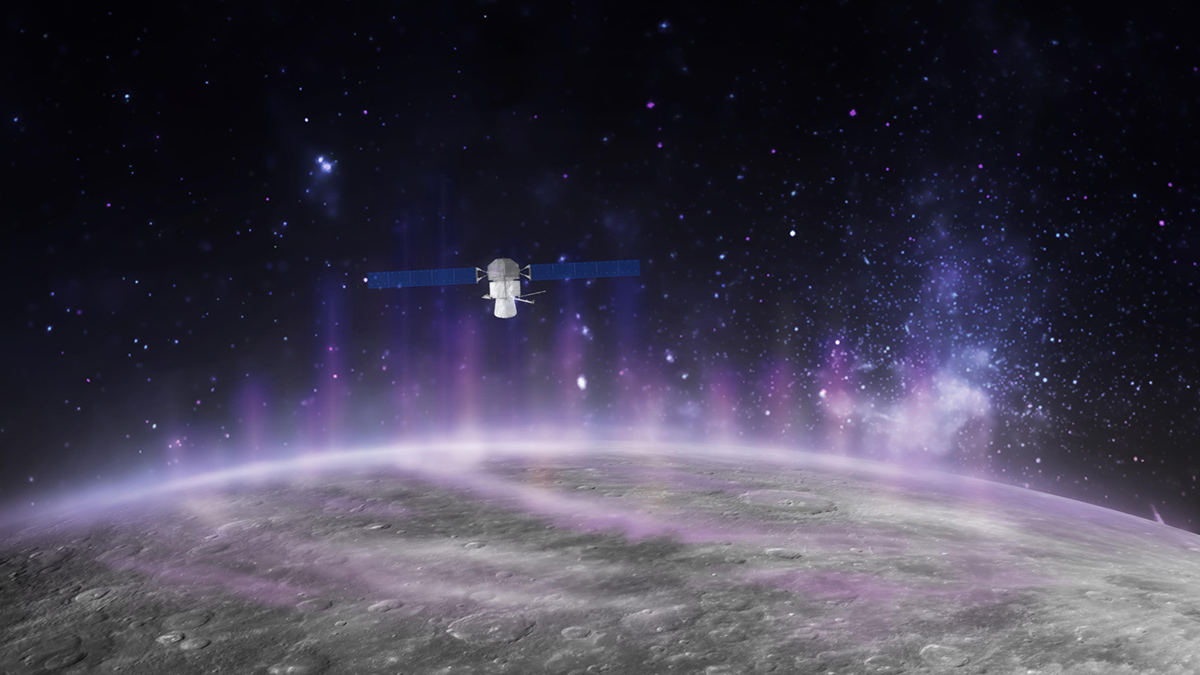

New research released by the Europlanet Society details the cause behind an even stranger aurora, the one that regularly wreathes Mercury with X-rays. This aurora arises from the planet’s surface, not its upper atmosphere, for reasons described in a new paper.

“For the first time, we have witnessed how electrons are accelerated in Mercury’s magnetosphere and precipitated onto the planet’s surface,” said physicist Sae Aizawa, who is affiliated with the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency, in a statement.

Joined at the Hip

It hinges on data from the BepiColombo space mission, a joint project between the European Space Agency and the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency.

Each side funded a probe—the Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, respectively—and the two flew to the planet in a docked configuration. They’ll remain joined at the hip for a total of seven years, until reaching final orbit around Mercury in 2025.

To get there, the joint spacecraft has taken a circuitous route, looping around Earth and Venus before gliding over to Mercury. During the next few years, BepiColombo will perform several flybys to slow down and ready itself for final orbit.

X-Ray Rain

On the first such barnstorming, in 2021, the pair came within 125 miles of Mercury and used plasma instruments to detect different types of charged particles in the solar wind. BepiColombo also measured the planet’s relatively small magnetosphere—including the magnetopause and the bow shock, areas where the magnetic field meets the solar wind. According to the data, the magnetosphere was in an unusually compressed state from the strength of said wind.

Researchers later concluded that charged particles fly up from the dark side of the planet and rain down on the dawn side, thereby releasing X-rays and producing the auroral glow. Unlike Earth’s magnetosphere, Mercury’s isn’t powerful enough to shield the planet from the solar wind.

“While Mercury’s magnetosphere is much smaller than Earth’s and has a different structure and dynamics, we have confirmation that the mechanism that generates aurorae is the same throughout the solar system,” said Aizawa.

—Matt Hrodey, Discover Magazine

This article was originally published by Discover magazine. Read the original article here.