When Europeans arrived in the Americas in 1492, they found two continents populated by as many as 60 million people: 10% of the world’s population. Within 100 years, 90% of indigenous Americans were dead from genocide and disease.

A new study in Quaternary Science Reviews links this abrupt loss in life to a dip in atmospheric carbon dioxide that may have contributed to the coldest snaps of the Little Ice Age.

The Little Ice Age describes a period of global cooling between roughly the 13th and 19th centuries that saw frozen rivers across Europe, crop failure and famine in Asia, and glacial expansion in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. This widespread cooling trend was likely triggered by a combination of increased volcanism, changes in ocean circulation patterns, and variations in Earth’s orbit.

Researchers associate a cold snap during the Little Ice Age with the loss of more than 50 million people in the Americas.

Embedded within the Little Ice Age are three notably colder intervals starting in 1610, 1770, and 1850, each separated by periods of slight warming. The new study proposes that the first of these dips may be rooted in the drastic population declines wrought by the European arrival in the Americas.

“Most of the Little Ice Age [was] caused by volcanic eruptions, fluctuations in solar output, and associated feedback processes,” says Alexander Koch, a geographer at University College London and lead author of the new study. “But the early 1600s, when temperatures were the coldest, coincides with the lowest carbon dioxide concentrations.”

Koch and his colleagues attribute this dip in atmospheric carbon dioxide—a greenhouse gas associated with warming—to the loss of more than 50 million people in the Americas in the preceding century.

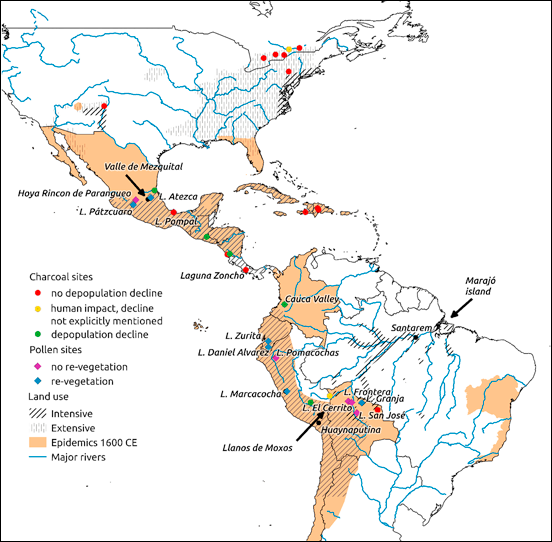

The hypothesis is not a new one, Koch says. The idea was first proposed in 2003 by University of Virginia paleoclimatologist William Ruddiman, but the new study offers a synthesis of previously published population data for the Americas, alongside statistics of land use change, altered fire regimes, and carbon uptake by regrowing plants and trees that led to the dip in carbon dioxide emissions.

“With drastically fewer people in the Americas, there was a lot less agriculture and a lot less burning,” Koch says.

Within a few decades, more than 56 million hectares of previously farmed and managed land—an area slightly smaller than the state of Texas—would have reverted to a wilder, more vegetated state capable of storing large amounts of carbon.

“What happened in the Americas, where a foreign force invaded and decimated the native populations of two whole continents, was unprecedented. It’s very different in scope from any other disease event or land use change event in history.”

Koch and colleagues estimate that between the reductions in burning and the rewilding of vegetation, the post–European contact land use changes in the Americas could have led to a drop of 3.5 parts per million in atmospheric carbon, enough to influence global climate. This drop in carbon dioxide is supported by ice core records, which show a decrease on the order of 7–10 parts per million during the coldest phases of the Little Ice Age.

Previous studies have offered evidence for declines in atmospheric carbon dioxide after smaller population declines associated with the Black Death in Europe and episodes of widespread famine in Asia.

“Pockets of population collapse tend to bounce back fairly quickly,” Koch says. “What happened in the Americas, where a foreign force invaded and decimated the native populations of two whole continents, was unprecedented. It’s very different in scope from any other disease event or land use change event in history.”

A Look at the Carbon Footprint of the Prehistoric Americas

The study adds to a growing body of work that supports a more dynamic view of the ancient Americas, says Robert Dull, a paleoecologist at the University of Texas at Austin who was not involved in the new study.

“Historically, scientists have largely ignored the carbon footprint of the Americas, pre–European contact, in large part because it is inconvenient and difficult to quantify,” Dull says. But one of the biggest contributors to carbon dioxide emissions in prehistory is human-set fires. “The paleofire community has demonstrated that prehistoric societies used fire extensively to manage lands and support agriculture. After European contact, fire use declined drastically.”

The main drawback of the new study is that it tackles such a huge area, spanning North, Central, and South America.

“This study does a really good job of showing what was happening in this hemisphere, but the detail is lost,” Dull says.

“It will be interesting to see more nuanced modeling organized by biome—tropical rain forests, temperate grasslands, hardwood forests—rather than by modern political boundaries,” he says. “I think we’ll see an even greater impact when we look at land use change and carbon sequestration in more detail.”

Ultimately, the new study’s researchers conclude that “human actions had global impacts on the Earth system centuries prior to the Industrial Revolution.”

Their findings may have some weighty implications for modern climate change, as human activities add about 2.3 parts per million of carbon to the atmosphere each year, an increase magnitudes of order greater than the 3.5 parts per million that were stripped from the atmosphere over the course of a century during the Little Ice Age.

“Despite its global impact at the time, the 3.5 parts per million decline in carbon dioxide is small compared to present-day conditions,” Koch says. “It really shows the magnitude of emissions that we produce today with the burning of fossil fuels.”

—Mary Caperton Morton ([email protected]; @theblondecoyote), Science Writer

This article is part of a series made possible through the generous collaboration of the writers and editors of Earth magazine, formerly published by the American Geosciences Institute.

Citation:

Morton, M. C. (2019), European contact with the Americas may have triggered global cooling, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO120119. Published on 08 April 2019.

Text © 2019. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.