The Hawaiian Islands, like many other regions of the world, have been experiencing the effects of severe drought for months. On an island like Maui, drought burdens ecosystems already under siege from invasive species, worsens water scarcity issues, disrupts agriculture and fisheries, and endangers Indigenous Hawaiian ways of living.

“This long-term decline in rainfall has resulted in acute stress in streamflow.”

Recent research led by Ayron Strauch, a hydrologist at Hawaii’s Commission on Water Resource Management at the Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR), has shown that over the past century, drought events have been increasingly common on Maui and other Hawaiian islands even during the wet season. Droughts have led to frequently dry freshwater streams, a situation that disrupts downstream ecosystems and slows groundwater recharge.

“We’ve had long-term decline in rainfall and long-term decline in streamflow, but we’ve seen acute declines in rainfall most recently.…The majority of months for the last 15 years have been below average,” Strauch said. “We’ve been experiencing longer-term drought conditions, both acute and persistent, as well as fewer but larger intensity storm events. This long-term decline in rainfall has resulted in acute stress in streamflow.”

Wai Supports Maui Ecosystems

“Water is extremely valuable on tropical islands,” Strauch said. “It’s used for drinking water supply, hydropower, agricultural irrigation, and it’s diverted from streams all across the state.” The groundwater aquifers beneath Maui are small, thin, and vulnerable to saltwater intrusion, so “depending on your location within the island, as much as 80% of your drinking water might come from surface water.”

In addition to these ecosystem services, streams help maintain the balance of biodiversity on Maui in freshwater ecosystems and transport nutrients to nearshore saltwater ecosystems like reefs. Too, fresh water, or wai, is sacred in Hawaiian culture, and a threat to streams also threatens the practice and preservation of Indigenous ways of life.

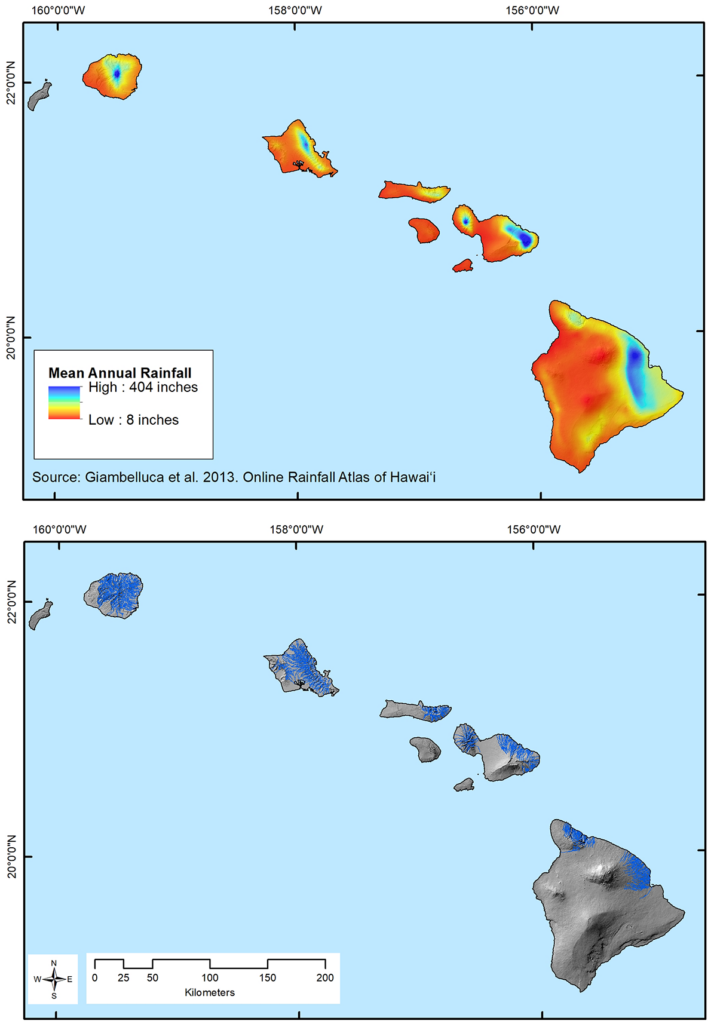

Using a combination of fieldwork, modeling, and archival information, Strauch’s team at DLNR and the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa examined streamflow rates and drought conditions across the island of Maui for the past 100 years. They found that although median annual rainfall rates have declined by only a few percent per decade over the past century, the geographic and temporal pattern of rainfall has shifted.

In recent decades, some regions on Maui experienced a modest (less than 5% per decade) increase in annual rainfall, whereas other regions have seen up to a 40% decline per decade. More significantly, a few intense storms released most of the rainfall, rather than the persistent and steady rainfall of decades past. Even during the 2022 wet season, the entire state of Hawaii experienced some state of drought; during the 2021 dry season, 29% of the state, including Maui, experienced severe, extreme, or exceptional drought.

“Our streams are very flashy,” Strauch said. “They respond quite rapidly to rainfall. If the rainfall isn’t distributed evenly across the year, our streams are still going to go dry because all that water just falls right off to the shore.” Moreover, Maui’s groundwater aquifers recharge through persistent rainfall rather than bursts, so not only do surface water sources remain dry, but groundwater reservoirs fail to recharge as well. Strauch presented this research at AGU’s Frontiers in Hydrology Meeting in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on 23 June.

Biodiversity Is Strength

The resilience of Maui’s ecosystems to drought lies in their biodiversity, explained Keoki Kanakaokai, the natural resource manager for the Maui terrestrial program of The Nature Conservancy in Hawaii. Invasive species—plants, animals, viruses, and pathogens—are the chief threat to that biodiversity.

“Invasive species worsen the impacts of drought, and drought worsens the impact of invasive species,” he said. Native plants like ‘ōhi‘a lehua evolved to efficiently gather water from the air, share water among other native species, and recharge groundwater reservoirs. Invasive plants like Himalayan ginger and strawberry guava tend to monopolize and hoard water, inhibiting groundwater recharge and depriving native plants. Invasive land mammals (any mammal except the Hawaiian hoary bat), but especially ungulates like pigs, goats, and deer, gouge the ground with their hooves, which worsens erosion and surface water retention. Then when drought and wildfires blight the landscape, invasive rather than native species are the first to grow back.

Too, dehydration of freshwater streams and increased erosion reduce the nutrients that flow to nearshore ecosystems and fisheries and increase harmful sedimentation. “As a Hawaiian growing up on the ocean, that’s always been the refrigerator,” Kanakaokai said. “But unfortunately, the impacts to our estuaries, our waterways, our nearshore fisheries and coral reefs, and our spawning grounds, in addition to marine invasions…all of those things combine to diminish our food security.”

“That loss of biodiversity, the loss of species, it makes our watersheds less abundant and less resilient to other invasions, other climate changes, and other changes on the landscape,” Kanakaokai said. Kanakaokai was not involved with this research.

Restoration and Kilo

Ultimately, swift and robust climate action will reduce the frequency and severity of drought on Maui and other Pacific islands. But much can be done in the meantime to mitigate the impacts of drought on island ecosystems. For example, building and maintaining fences can keep invasive ungulates from damaging vulnerable ground and spreading non-native plant seeds and pathogens.

What’s more, “if we controlled certain invasive [plants] and restored our native forests, we could improve groundwater recharge by 5% or 8%, which could be huge,” Strauch said. “That could be the difference between major suffering from lack of water to being okay.”

Conservationists like Kanakaokai and others across the islands work diligently to curb the invasion of non-native plants and restore native forests, including reestablishing many plant species that are on the brink of extinction. Although the restoration work is becoming more difficult each year, he said, “the wonderful thing is there’s so much that can be done…if we control the threats, remove the threats from the landscape, then our native species can rebound. It still has that resilience built into it.”

In addition to restoring species to their native landscapes, Kanakaokai said that there has been great progress in propagating endangered native species in greenhouses, in plant nurseries, and even in suburban landscaping around houses, schools, and new developments. Communities across Hawaii are increasingly embracing sustainable agriculture and restoration of native landscapes.

“We take into consideration more than just Western empirical science but also incorporate Traditional Ecological Knowledge [and] traditional ways of knowing. In particular, we value things like kilo, the Hawaiian concept of observation and building relationships with our resources.” Hawaiian cosmogony includes recollections of life forming in an evolutionary manner, he explained, so “Hawaiians view these [ecosystems] as our ancestors. We view these as our own histories that are sacred, that need to be protected for their inherent value to us as family members.”

—Kimberly M. S. Cartier (@AstroKimCartier), Staff Writer