One of the world’s biggest producers of oil and gas may face billions in upgrades as permafrost thaw destabilizes pipelines in the Arctic, according to new research.

Russia produces 80% of its natural gas in the Arctic, where rising temperatures are thawing ground that has been frozen for tens of thousands and even hundreds of thousands of years.

“Natural gas pipelines appear to be particularly vulnerable,” said Meredydd Evans, an Earth scientist with the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, because natural gas extraction occurs a little farther north—and more into permafrost territory—than oil extraction.

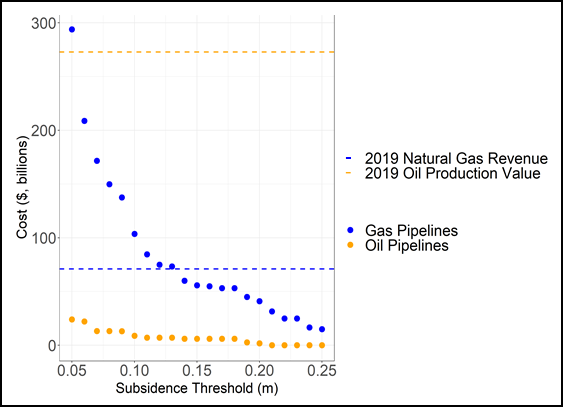

Evans and a team of scientists at national laboratories in the United States compared Russian oil and gas pipeline routes with projected ground subsidence from permafrost thaw. When permafrost melts, the ground level sinks, sometimes by several centimeters and sometimes by more than a dozen centimeters per year.

A soil slump of even 10 centimeters can be enough to inflict damage.

Most Russian pipelines are underground, making them particularly vulnerable to shifting soil. Soil settling unevenly deflects and deforms pipelines, and water pooling around the pipes corrodes them.

The ground beneath gas pipelines may subside up to half a meter in places over the next 20 years, according to the group’s permafrost projections. A soil slump of even 10 centimeters can be enough to inflict damage on pipelines.

The costs add up: If emissions stay the same, cumulative costs will reach US$110 billion (8.1 trillion rubles) by 2040. Repairs to natural gas pipelines during that time could rival the revenue of natural gas gained in 1 year. “We were just struck by that,” said Evans.

The Yamal Peninsula, which may hold 100 years’ worth of natural gas reserves, is a hot spot for subsidence. The permafrost there contains more ice than in other areas, making the soil particularly vulnerable to warming, said Evans. She will present the work, which has not been peer reviewed, on 17 December at AGU’s Fall Meeting 2021.

Previous research found that permafrost thaw may cost the Russian Arctic 14 billion to 28 billion rubles in annual road repair between 2020 and 2050.

Oil and gas are key economic revenue sources for Russia, the world’s third-largest producer of oil and second-largest producer of natural gas. Costly repairs could hamper economic development in the region, but state support may buoy the industries.

High costs could change how oil and gas are transported in the future, said Evans. Rather than building more pipeline, the country could ship reserves. Shipping in the Arctic gives off soot, or black carbon, that darkens snow and quickens melt.

“Sixty-five percent of Russia’s territory is located in the permafrost zone, but this is not mentioned in a single federal program document.”

“Sixty-five percent of Russia’s territory is located in the permafrost zone, but this is not mentioned in a single federal program document, despite the fact that the permafrost area is a vital component in the natural environment, of which the landscape, vegetation and coastline is dependent,” Aleksander Kozlov, Russian minister of natural resources and the environment, said in a statement (translated by the Barents Observer). More than 40% of Russia’s northern buildings are starting to collapse, he said.

Kozlov announced that the country is launching a new state system for monitoring permafrost. Regional initiatives are picking up steam, too: A lab dedicated to permafrost studies—the first of its kind in Russia—will open in the Yamalo-Nenets region in 2022.

Newly constructed pipelines in Russia have more modern features, such as thermal siphons around the pilings that hold the pipes aboveground. In one state-owned gas field, pipes circulating refrigerant cool the soil underground.

But these interventions are expensive, said Evans.

Because permafrost is likely subsiding earlier in Russia than in other Arctic areas (such as Alaska), pipeline damage may be a bellwether for other regions, she said. “Just understanding what’s happening in Russia could be helpful and informative.”

—Jenessa Duncombe (@jrdscience), Staff Writer