As stellar neighbors go, the Sun is a pretty good one—it occasionally produces a sizeable solar flare, but mostly, it leaves Earth well enough alone. The Proxima Centauri solar system isn’t so lucky, however: Blasts of electromagnetic radiation from Proxima Centauri, the next nearest star to our own, can be potentially lethal to nearby planets.

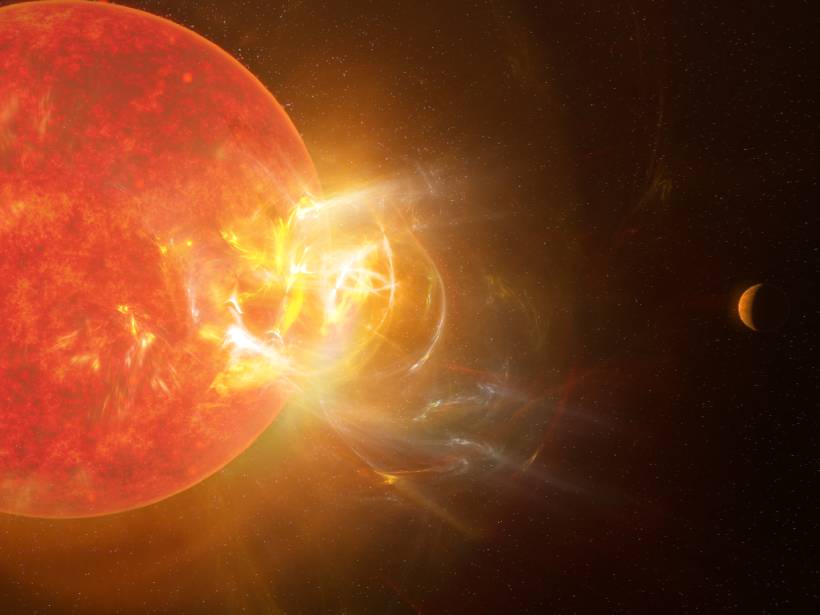

Researchers recently spotted the brightest stellar flare ever detected from Proxima Centauri. That flare might have contributed to stripping away the atmosphere of one of its planets, a roughly Earth mass world that potentially hosts liquid water on its surface.

Destroyer of Atmospheres

Proxima Centauri is located 4.2 light-years away, yet it’s much too faint to see with the naked eye. (Polaris, the North Star, is more than 400 light-years distant, for comparison.) Proxima Centauri’s faintness stems from its low mass—it’s what astronomers refer to as an M dwarf star, defined as having a mass between roughly 10% and 50% the mass of the Sun. M dwarf stars are the most common stars in the Milky Way, but they come with a reputation, said Meredith MacGregor, an astronomer at the University of Colorado Boulder. “M dwarfs are vastly more active than the Sun.”

“You can basically erode away the atmosphere of a planet.”

That means they regularly emit stellar flares, blasts of electromagnetic radiation launched by their host star’s magnetic field. These streams of photons can be destructive, said MacGregor. When high-energy ultraviolet radiation collides with a planet’s atmosphere, it can disassociate molecules like water and ozone, splitting them into their constituent atoms. Some of those lighter atoms can then drift away and escape. “You can basically erode away the atmosphere of a planet,” said MacGregor.

And They’re Off!

In 2015, unbeknownst to earthly observers, Proxima Centauri let loose an enormous flare. The photons streamed through the Proxima Centauri solar system—with its two known planets—and continued out into interstellar space.

“This star is brightening in the ultraviolet by a factor of 14,000.”

A little more than 4 years later, MacGregor and her colleagues were observing Proxima Centauri using up to nine research telescopes simultaneously, five on the ground and four orbiting Earth. (Such coordinated observing is an astronomical tour de force, and it required a whole lot of communication among different observing facilities, said MacGregor.) On 1 May 2019, the team spotted a whopper of a flare. “This star is brightening in the ultraviolet by a factor of 14,000 in just a couple of seconds,” said MacGregor. “That challenges our picture of flaring.”

It’s the brightest stellar flare ever detected from Proxima Centauri and about 100 times brighter than the largest flares produced by the Sun, MacGregor and her collaborators deduced. This event is a record setter, said MacGregor, but it’s probably not unique. “The star is doing this very frequently.”

Similarities Across the Spectrum

The researchers made a surprising discovery: The flare behaved remarkably similarly in observations at millimeter wavelengths (in the radio part of the electromagnetic spectrum) and in the ultraviolet. It brightened and diminished at very nearly the same times in both data sets, said MacGregor. “The millimeter and ultraviolet light are very tightly correlated.”

That’s intriguing, the team suggests, because ultraviolet measurements are somewhat of a holy grail when it comes to stellar flares: Getting a handle on this high-energy emission is critical to understanding whether flare activity might be stripping a planet of its atmosphere or, perhaps, even kick-starting life. But it’s downright difficult to measure ultraviolet light on Earth since our planet’s atmosphere blocks most of its wavelengths, said Katherine Garcia-Sage, a space physicist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., not involved in the research. “We can’t detect them from the ground.” (The Hubble Space Telescope, in orbit roughly 550 kilometers above Earth, is one of the only telescope facilities that can detect ultraviolet light.)

But millimeter-wavelength emission can be readily detected from Earth’s surface using radio telescopes, said MacGregor. “If the millimeter really is tracing the ultraviolet, we might be able to use these millimeter observations to infer what the ultraviolet light is doing during these events.”

These results were published last month in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

MacGregor and her colleagues are continuing to sift through all the data they collected in 2019. They have roughly 40 hours of observations, and there are likely plenty more flares in their data set, said MacGregor. In the future, the team also hopes to collect similar observations of other stars to determine whether Proxima Centauri’s flaring is exceptional or simply a way of life for M dwarf stars.

—Katherine Kornei (@KatherineKornei), Science Writer

Citation:

Kornei, K. (2021), Record-setting flare spotted on the nearest star to the Sun, Eos, 102, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO158820. Published on 24 May 2021.

Text © 2021. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.