What a disappointment it must have been: Just 1 year after miners in southeast interior Alaska blasted through a ridge to redirect a tributary of the Yukon River, they abandoned the site, leaving a drastically changed waterway.

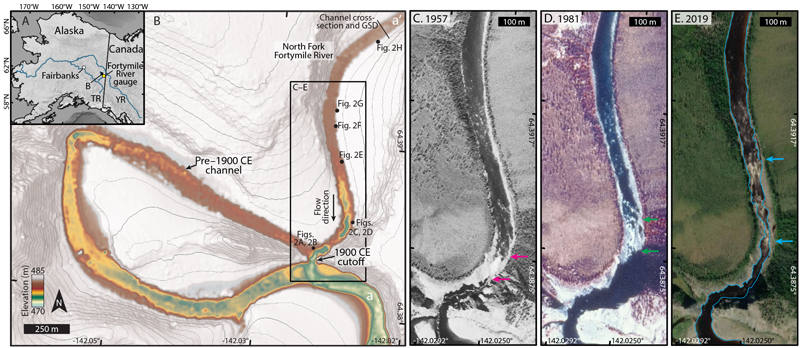

Instead of flowing around a more than 3-kilometer meander, the North Fork of the Fortymile River cut directly through a 30-meter ridge. Miners deserted the site in 1901, wrote local historian Elva Scott, because a landslide covered their mining site just 1 year after the blast.

But U.S. Geological Survey geomorphologist Adrian Bender said the debacle kicked off a perfect scientific experiment.

“As a scientist thinking about how the river responds, it couldn’t be more perfect that the miners would make this massive change and then just walk away within a year,” Bender said.

Geomorphologists often arrive long after nature’s forces have been at work. But Bender found historical observations and photographs of the canyon going back to 1900 when the blast occurred. Along with measurements taken in 2018, it was possible to document the river cutting into the bedrock in real time over its 119-year life.

The work revealed how rivers change the way they sculpt the landscape even on short timescales, said Brian Yanites, a geomorphologist at Indiana University Bloomington who was not involved in the work. “What [Bender] documents in 100 years would take a river in the most dynamic landscapes many millennia to erode.”

A Canyon’s Life

In 1900, gold miners working for an English investment corporation set off dynamite to blow a 5-meter gap in a 30-meter ridge. The site, now called The Kink in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, sits on the traditional land of the Hän and Dënéndeh people.

Within hours of the explosion, the river abandoned the old channel and rushed down the new one, tearing at the bedrock and more than doubling the size of the gap.

Over the next century, the new channel would morph from a waterfall into a series of rapids and would reveal how bedrock canyon incision works.

In the first 3 years of its life, the channel changed rapidly. The waterfall—also referred to as a knickzone, or an unusually steep section of a river—moved upstream at a quick clip of 23 meters per year on average.

Over the next 80 years, the waterfall flattened out into a series of rapids and only slowly moved upstream (about 4 meters per year on average). Since the 1980s, the base of the knickzone has stalled, but the top has continued to move upstream, said Bender, who published the work in the journal Geology.

The river’s changes reveal underlying forces at work. When the new channel first formed, it was so steep that it carried mailbox-sized rocks downstream with ease. The debris battered the canyon’s crystalline bedrock, scouring the channel drastically. Its slope decreased fourfold over the first 60 years.

Once the river became less steep, erosion continued, but the process behind it changed. Before, the steepness of the waterfall brought boulders to erode its bank. Now, the flow of the river must be above average to carry large rocks to chip away at the channel.

Scientists use the terms “transport limited” and “detachment limited” to compare these two types of river processes, and the latest work shows how one river can transition from one type (detachment limited) to another (transport limited) after a significant event.

Understanding how canyons form can help scientists interpret faults or earthquakes. With the right information, researchers could explain how recent uplift happened at a fault, for instance, by looking at the shape of a river canyon that bisected it. In Taiwan, an earthquake in 1999 boosted one side of a river by two stories, causing the channel to slice a 1,200-meter long gorge in the Da’an River.

“Rivers are the agents of erosion and sediment transport,” Bender said. “Understanding how rivers do that work is fundamental to understanding how landscapes change over time.”

—Jenessa Duncombe (@jrdscience), Staff Writer

This news article is included in our ENGAGE resource for educators seeking science news for their classroom lessons. Browse all ENGAGE articles, and share with your fellow educators how you integrated the article into an activity in the comments section below.