Giant catfish once swam in the golden-brown waters of the Mekong River near the Thai village of Sob Ruak. But since the Chinese government built hydropower dams upstream, the waters now drop too low for the catfish to lay their eggs. The loss of habitat for the catfish is just one of many stressors the increasingly developed river faces.

A new study released 8 May in the journal Nature suggests that the Mekong’s plight is not unique: Humans have significantly impacted the majority of the world’s 242 longest rivers. Just one third of long rivers still flow freely throughout their entire length, and the most untouched rivers exist far from population hubs in the Arctic, the Amazon River Basin, and the Congo River Basin.

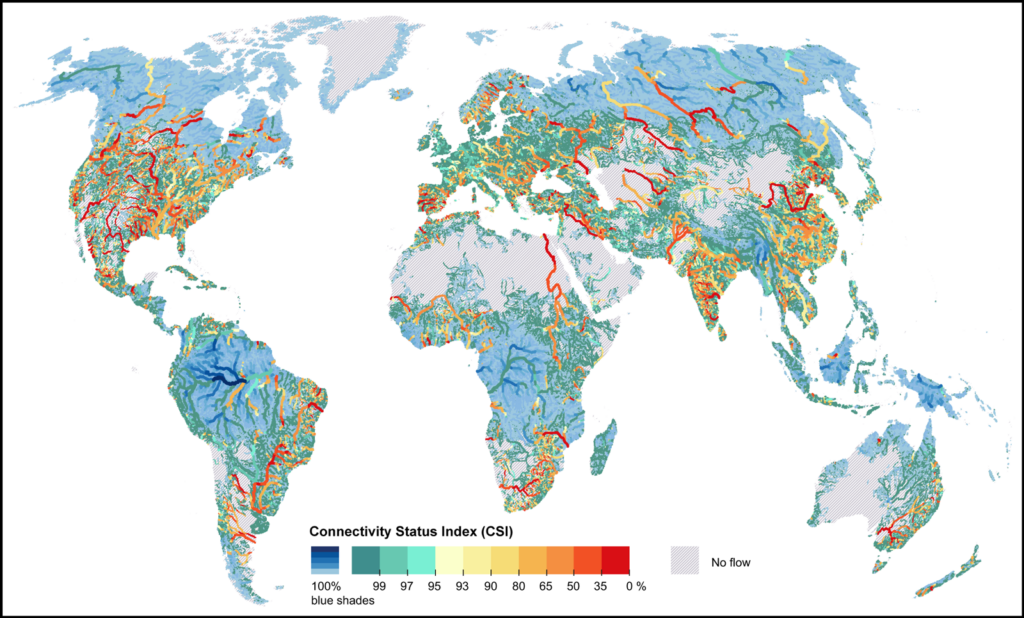

The study includes detailed worldwide river maps that give planners a bird’s-eye view of human changes across the landscape. As countries race to meet aggressive clean energy goals, the study’s authors hope that the maps can inform future hydropower dam projects.

“This study is not meant to be a study that says ‘stop any kind of development,’” Bernhard Lehner, an associate professor in the Department of Geography at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, and one of the first authors on the study, told Eos. “But it’s meant to find smart solutions.”

Free to Roam

In the past, scientists relied on hydrologic assessments limited in scope. They used either global data sets of rivers that suffered from low resolution or regional maps that failed to take the whole watershed into consideration. The latest assessment is novel in both its reach and detail.

The team parsed 12 million kilometers of rivers and rated the rivers’ degrees of freedom. A free-flowing river can move side to side and ebb and flow naturally, as well as have the ability to replenish groundwater and carry sediment. A free river should also start at its source and flow unimpeded to its end. Together, the scientists call the criteria “four-dimensional” connectivity.

The researchers rated their 12-million-kilometer database in 4-kilometer-long sections. They docked a section’s free-flowing status not only for infrastructure like dams and reservoirs but also for projects less easily seen, like sediment traps and irrigation. They even mapped canals using satellite images of night light. The study limited its assessment to rivers longer than 500 kilometers because smaller dams and modifications often go unreported.

The analysis revealed not only that most of the world’s longest rivers are no longer free-flowing but also that dams are the overwhelming cause.

“We always come back to dams as being the main culprit in all this,” Lehner said.

Dams stop species from migrating upstream, and they also trap sediment, preventing it from flowing down the river. For the Mekong River, more dams will mean less and less sediment transport to the fertile Mekong River Delta in southern Vietnam, a hub of the country’s agriculture. The Mekong rates below the threshold for a healthy, free-flowing river in the study’s assessment.

Murky Waters

Although dams fragment a river and cause a litany of downstream damages, they also provide a source of renewable energy. There are increasingly urgent calls worldwide for lowering greenhouse gas emissions, and hydropower dams are one answer.

Climate change driven by greenhouse gas emissions harms rivers as well: Hotter air temperatures warm river waters and decrease the amount of dissolved oxygen they can hold. Restricting the free flow of rivers by installing hydropower dams will hurt the ecosystem further, according to the new study.

“While we try to counter climate change, it makes the situation in rivers worse for ecology,” Lehner noted. “This is the conundrum in this whole story.”

Lehner hopes that the new data set, which is available with its source code for free, will give planners a resource to scrutinize the full effects of river management infrastructure.

“Such a global map of four-dimensional connectivity allows our community to devise solutions for river infrastructure that are more ecofriendly, greener, and yet can address livelihood needs.”

“We can run thousands of scenarios where we place dams in different locations and see what that would do to [river] connectivity,” Lehner noted. If a dam must be built, he reasoned, planners can leverage the tool to put it in the least impactful place for river connectivity possible.

Faisal Hossain, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Washington not involved in the study, told Eos that the new research gives engineers like him “an actionable map.”

“Such a global map of four-dimensional connectivity allows our community to devise solutions for river infrastructure that are more ecofriendly, greener, and yet can address livelihood needs,” he noted.

“This is a very brilliant breakdown for the engineering and policy world,” he said.

The study’s maps can be explored in this interactive map portal.

—Jenessa Duncombe (@jrdscience), News Writing and Production Intern

Citation:

Duncombe, J. (2019), Where did all the free-flowing rivers go?, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO123209. Published on 08 May 2019.

Text © 2019. AGU. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.

Text © 2019. AGU. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.