Editors’ Highlights are summaries of recent papers by AGU’s journal editors.

Source: AGU Advances

If you spin a bowling ball, the finger-holes will end up near the rotation axis because putting mass as far from the axis as possible minimizes energy. So, on planets –if there is a large mountain, it will end up at the equator; in physics terms, the axes of rotation and maximum inertia align.

Conversely, a planet that is very spherical will be rather unstable, so that the solid surface can move relative to the rotation axis, so-called true polar wander (TPW). Because of its slow rotation, Venus is extremely spherical; TPW can thus easily occur, driven for example by mantle convection, which is time-dependent. Furthermore, Venus’s axes of maximum inertia and rotation are offset, by about 0.5o.

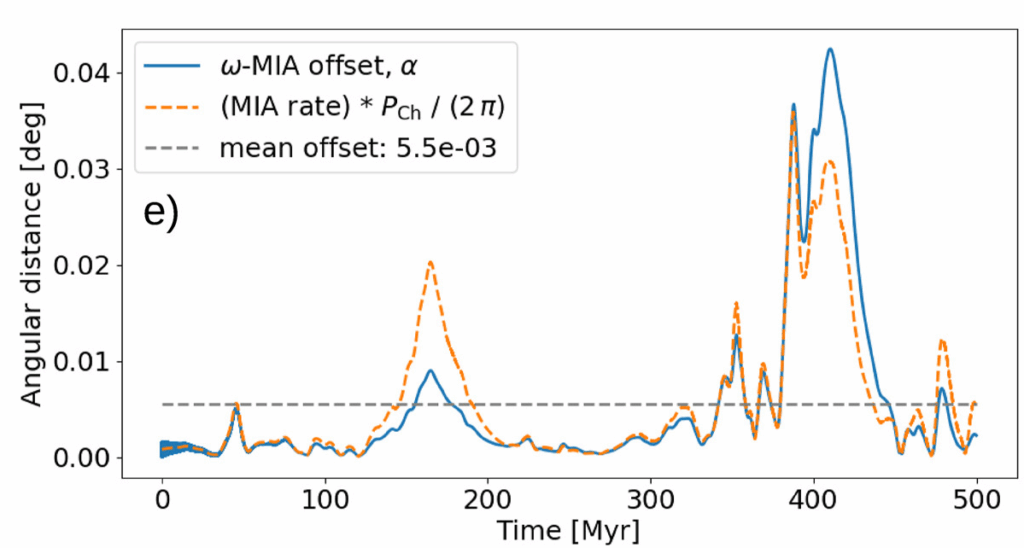

In a new paper, Patočka et al. [2025] analyze the effect of convection on Venus’s axial offset and potential for TPW. They find TPW rates that are consistent with geologically-derived values, but that the resulting axial offset is much smaller than observed. Their conclusion is that atmospheric torques are likely responsible, as they probably are for the apparent variations in Venus’s rotation rate measured from Earth.

Three spacecraft missions will soon be heading to Venus. Direct measurement of the effects predicted by the researchers are challenging, but the coupling between atmospheric dynamics and planetary rotation will surely form an important part of their investigations.

Citation: Patočka, V., Maia, J., & Plesa, A.-C. (2025). Polar motion dynamics on slow-rotating Venus: Signatures of mantle flow. AGU Advances, 6, e2025AV001976. https://doi.org/10.1029/2025AV001976

—Francis Nimmo, Editor, AGU Advances