Source: Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems

Variations in the temperature of the mantle drive its convective circulation, a process that links the deep mantle with the atmosphere and oceans through volcanic and tectonic activity. Because of this connection, effective models of Earth’s evolution must incorporate the planet’s thermal history, for which a crucial constraint is the mantle’s current temperature.

Because the mantle’s temperature cannot be measured directly, scientists have devised a number of creative methods to derive this information, but these have produced widely varying results. Now Matthews et al. offer new constraints on this parameter beneath Iceland, one of the few places on Earth where a divergent plate boundary is subaerially exposed because of an anomalously large amount of melting occurring beneath the island.

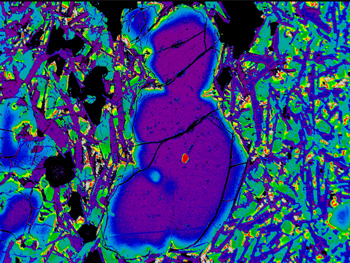

Using a recently developed mineral thermometry technique, the researchers found that lava flows from four different eruptions along Iceland’s Northern Volcanic Zone crystallized at substantially higher temperatures (maximum 1399°C) than average mid-ocean ridge samples that have experienced little melting (maximum 1270°C). Next, the team developed a thermal model of mantle melting and used it, along with other observations such as the local thickness of the crust, to quantify the uncertainties in deriving mantle temperatures from their data.

Their results indicate that the mantle below Iceland is at least 140°C hotter than that beneath average mid-ocean ridges. This outcome should shed light on the factors that control the extent of melting beneath Iceland, including the ongoing debate about whether the voluminous melting is due to a deep mantle plume and, if so, whether changes in its magma production reflect variations in the plume’s temperature. (Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, doi:10.1002/2016GC006497, 2016)

—Terri Cook, Freelance Writer

Citation:

Cook, T. (2016), A significantly hotter mantle beneath Iceland, Eos, 97, https://doi.org/10.1029/2016EO062987. Published on 18 November 2016.

Text © 2016. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.