Source: Earth’s Future

It’s well known that anthropogenic warming will affect global climate and sea levels far into the future. At the edges of ice sheets and glaciers, water, air, and ice all come together in a complex union that carries implications for predicting climate in the future. As global temperatures rise, ice sheets and glaciers melt, dumping their meltwater into the ocean. The future of some areas, such as the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), remains a wildcard when it comes to predicting how the oceans might change.

The WAIS spans much of West Antarctica and holds 2.2 million square kilometers of ice. To try and piece together how the ice sheet might change in the future, Fogwill et al. used climate models to examine the meltwater’s potential effects, focusing on three specific Antarctic regions: the Amundsen, Ross, and Weddell embayments. The scientists’ experiments considered numerous scenarios, ranging from only portions of the ice sheet disappearing to complete melting.

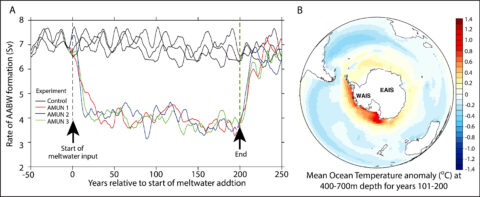

Fresh water flowing off the ice sheet reduces the salinity and density of the ocean’s surface water. With lower-density water sitting on top, the ocean’s vertical layers become more distinct and don’t mix as much. The researchers also found that the formation rate of Antarctic Bottom Water—a layer of dense cool water that pools near the ocean floor—decreased by 25%–50% within decades when compared to a preindustrial control. In all scenarios, the results show that waters ranging from 400 to 700 meters in depth will warm rapidly within the first 200 years, with warming at depth fluctuating between 0.5°C and >1°C, depending on the scenario.

The scientists demonstrated that an increase in fresh meltwater from the WAIS decreases ocean salinity and increases water temperatures in critical locations around the edge of the Antarctic ice sheet, including areas of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS). In addition, by investigating specific sites along the ice sheet’s edges, the researchers showed that the location of melting is just as critical to ocean dynamics as the volume of meltwater flowing into the ocean, with sites such as the Amundsen Sea, an area of rapid contemporary WAIS change, being critical.

These effects extend beyond the Southern Ocean. Although the impact is strongest there, all across the Southern Hemisphere, salinity and water temperature are changing. In these models, however, the scientists didn’t include rising atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, which could accelerate the rate of ice sheet melting. Given that, the estimations provided could be conservative. (Earth’s Future, doi:10.1002/2015EF000306, 2015)

—Cody Sullivan, Writer Intern

Citation: Sullivan, C. (2016), Antarctic meltwater makes the ocean warmer and fresher, Eos, 97, doi:10.1029/2016EO044811. Published on 1 February 2016.

Text © 2016. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.