Source: Global Biogeochemical Cycles

A translation of this article was made by Wiley. 本文由Wiley提供翻译稿。

For years, oceanographers have puzzled over why algorithms were detecting mysteriously high levels of particulate inorganic carbon (PIC) in satellite imagery of remote Antarctic waters. In other areas, high PIC is a sign of massive blooms of single-celled phytoplankton known as coccolithophores, whose shiny calcium carbonate shells reflect light back to satellites. However, these polar waters have long been thought to be too cold for coccolithophores to thrive in.

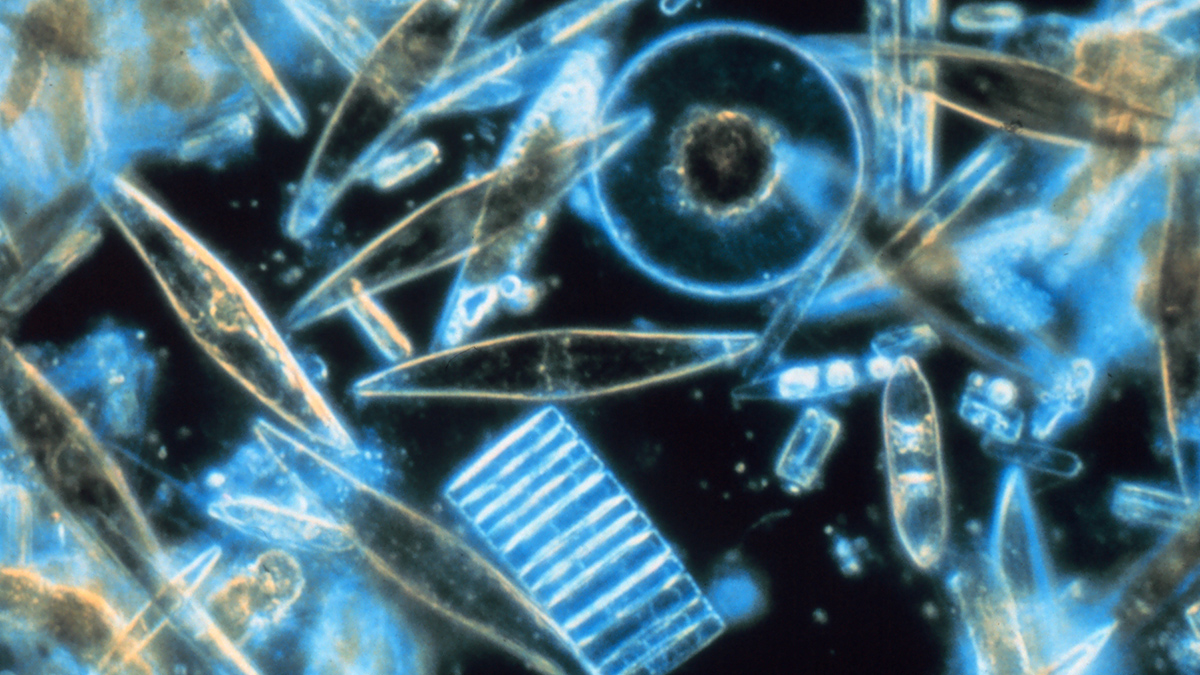

The mystery is now solved, thanks to new ship-based measurements from Balch et al. They discovered an abundance of a different type of phytoplankton known as diatoms, whose reflective silica shells, or frustules, can mimic the reflectivity of PIC when found at very high concentrations. This reflectivity can lead satellite algorithms to misclassify these far southern waters as high-PIC areas.

Earlier ship-based observations from the same research team had already confirmed that PIC from coccolithophores is responsible for the Great Calcite Belt—a massive, seasonal, reflective ring of water encircling Antarctica in warmer waters to the north. Farther south, however, unusually bright areas around the continent remained unexplained, with hypothesized causes including loose ice, bubbles, or reflective glacial “flour” (eroded rock particles) released into the ocean.

The researchers sailed south from Hawaii into the less explored waters—known for their icebergs and rough seas—aboard R/V Roger Revelle. They measured PIC and silica levels, determined photosynthesis rates, conducted optical measurements, and observed microbes under microscopes. Together the data revealed that the high reflectivity of these remote areas is primarily caused by diatom frustules.

However, the researchers were also surprised to detect some coccolithophores in the polar waters, suggesting these phytoplankton can survive in seas colder than previously thought.

The findings could have key implications for Earth’s carbon cycle, as both coccolithophores and diatoms play major roles in the fixation of oceanic carbon. This work could also inform improvement of satellite algorithms to better distinguish between PIC and diatom frustules, the researchers suggest. (Global Biogeochemical Cycles, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GB008457, 2025)

—Sarah Stanley, Science Writer