Source: Geophysical Research Letters

Albedo, a measurement of how much solar radiation is reflected back to space by a planet or a moon, plays an important role in calculating Earth’s energy budget and predicting climate change. Dark parts of the planet trap incoming solar radiation and increase the temperature, whereas lighter ones reflect more radiation and keep Earth cool. Unfortunately, one of the best reflectors of solar radiation also happens to be extremely vulnerable to rising temperatures: ice.

Satellites like NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) have given scientists the opportunity to remotely measure Earth’s albedo across huge distances and long time periods. Historically, these satellites have relied on on-the-ground weather stations to validate and calibrate their measurements, but in a new study, Ryan et al. suggest that these “ground truth” measurements may sample too small of an area to adequately capture the full extent of variance in albedo across heterogeneous landscapes, leading to an overestimation of how reflective our planet actually is.

The new study draws its data from a series of weather stations across the Greenland ice sheet. The stations contain instruments called pyranometers, which are typically mounted about 2.8 meters above the ground and measure how much solar radiation is coming down onto the planet versus how much is being reflected back. Pyranometer data can then be used to correct for disturbances in MODIS’s measurements caused by the planet’s atmosphere.

The calibration/validation process is complex, but the general idea is that the pixel that contains the weather station should have the same albedo measurement as the pyranometer on the ground. However, because the weather station measures albedo from a land area smaller than one satellite pixel, the comparison is not perfect. The calibration/validation process is dependent upon the assumption that albedo around a weather station does not vary.

In an effort to determine whether this assumption was valid, scientists used a fixed-wing unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), or drone, to survey the albedo across an entire satellite pixel—a true “point to pixel” comparison—and found that the spacecraft was actually more accurate than previously thought.

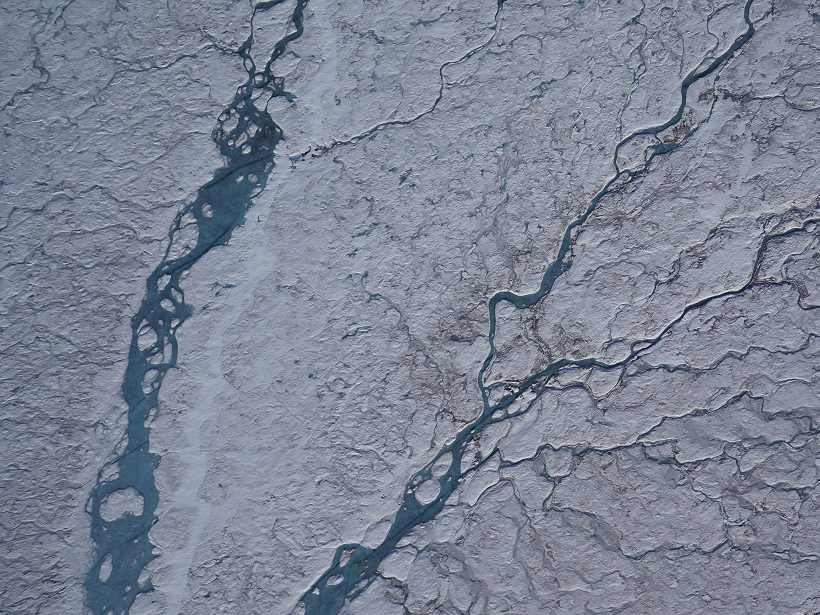

The researchers argue that the discrepancy arises because on-the-ground measurements sometimes do not encompass an area large enough to be representative of the whole satellite pixel. In fact, the grounded pyranometers tend to overestimate albedo because they don’t take into account larger-scale phenomena, such as changes in topography, which can reduce the planet’s reflectivity—like scratches or bumps on a mirror. Weather stations are typically placed on flat, stable ground, which may create a systemic bias in their data. They also may fail to adequately capture the variability in landscapes that are actively melting, where snow and ice conditions are most heterogeneous.

The bias, the researchers say, leads to an overestimation of albedo by up to 0.10, or 10% (albedo is the percentage of the Sun’s energy that is reflected back by the surface, so measurements can be expressed between 0 and 1). To rectify these biases, the team suggests using multiple pyranometers within the confines of a single satellite pixel for calibration and validation. They also suggest ignoring data from pyranometers in heterogeneous landscapes and using more fixed-wing UAV surveys to create truer comparisons.

Because albedo is such a key measurement in determining the Earth’s energy balance, calculating it precisely has important implications for predicting the future of the planet’s climate. If ground truth measurements from weather stations are failing to represent landscape diversity across a satellite pixel, scientists may have been underestimating how much of the Sun’s energy is being absorbed by Earth. (Geophysical Research Letters, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL073661, 2017)

—David Shultz, Freelance Writer

Citation:

Shultz, D. (2017), On-the-ground measurements overestimate Earth’s albedo, Eos, 98, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO079555. Published on 18 August 2017.

Text © 2017. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.